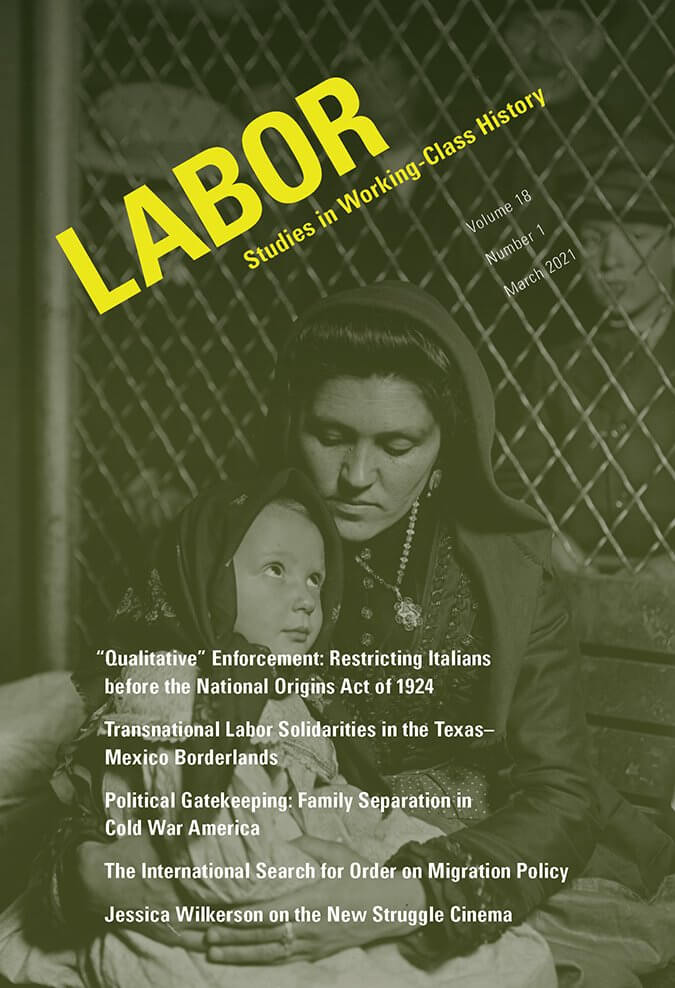

Duke University Press, the publisher of Labor: Studies in Working Class History, has just released the 5 most read articles from Volume 18 from behind the paywall. They are free until January 31, 2022.

Please share these freely available articles with your colleagues and students. Julie Greene’s essay is a great introduction to the field of labor history. The others are great interventions on issues of immigration, deportation, radical labor, race and civil rights. Jessica Wilkerson suggests some great winter movies to view.

- Rethinking the Boundaries of Class: Labor History and Theories of Class and Capitalism

by Julie Greene- This article examines how the field of labor and working-class history has conceptualized class and assesses theories of class that can help us develop maximally illuminating concepts. Labor historians, particularly those whose work employs a transnational, gender, or racial lens of analysis, have advanced our understanding of how working people’s lives are shaped by class. By connecting that scholarship to class theory, the article argues for reconceptualizing class to focus on the complex ways capitalism generates class relationships, embedding race, gender, and other historical dynamics within its formative parameters. It relies on work by Tithi Bhattacharya and Stuart Hall to articulate a specific vision of class relations under capitalism. Finally, the article concludes with praxis by applying Hall’s and Bhattacharya’s insights to the challenges academic knowledge workers face today amid the crisis of higher education, which is growing more pressing as a result of the economic disaster related to the COVID-19 pandemic. It concludes by addressing how our conceptualizations of class could shape efforts to build broad solidarities among knowledge workers in higher education.

- “Did Emmett Till Die in Vain? Organized Labor Says No!”: The United Packinghouse Workers and Civil Rights Unionism in the Mid-1950s

by Matthew F. Nichter- Emmett Till’s mangled face is seared into our collective memory, a tragic epitome of the brutal violence that upheld white supremacy in the Jim Crow South. But Till’s murder was more than just a tragedy: it also inspired an outpouring of protest, in which labor unions played a prominent role. The United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) campaigned energetically, from the stockyards of Chicago to the sugar refineries of Louisiana. The UPWA organized the first mass meeting addressed by Till’s mother, Mamie Bradley; packinghouse workers petitioned, marched, and rallied to demand justice; and an interracial group of union activists traveled to Mississippi to observe the trial of Till’s killers firsthand, flouting segregation inside and outside the courtroom. Analysis of antiracist unions like the UPWA can help rectify a weakness in the “whiteness” literature by illuminating the contexts and strategies that have fostered durable interracial working-class solidarity. The UPWA, which managed to survive the Red Scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s relatively unscathed, represents an important link between the “civil rights unionism” of the 1930s and 1940s and the civil rights movement of the mid-1950s and 1960s.

- Barring the Gate: A History of Political Exclusion and Family Separation in Cold War America

by Adam Goodman- When long-term Chicago resident and World War II veteran Rodolfo Lozoya traveled to Mexico in 1957 to visit his ailing mother, he probably did not think that he would face the threat of permanent separation from his US citizen wife and children. But when he tried to reenter the United States, authorities excluded him from the country because of his alleged past membership in the Communist Party. The saga of Lozoya’s exclusion and his family’s separation offer insights into the hypocritical nature of democracy in Cold War America. The case also sheds light on the intertwined lives of citizens and noncitizens, and how immigrant rights groups such as the Midwest Committee for Protection of Foreign Born mobilized to defend people from exclusion and deportation under the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952. Federal censors’ decision to withhold materials on Lozoya more than fifty-five years later, and thirty years after his death, points to the enduring legacy of the Cold War and to the pervasive fear of radical politics in the twenty-first century.

- Representing Working-Class Lives, Struggle, and Movements in Twenty-First-Century Films

by Jessica Wilkerson- Over the last several years, there has been an uptick in the number of films that address class, power, inequality, and global capitalism. Writers and directors have taken up these themes in feature-length films and documentaries and against the backdrop of the Great Recession, the Occupy movement, the Movement for Black Lives, #MeToo, and the rise of Trumpian nativism. Eschewing any sense of a monolithic working-class character, the films represent a twenty-first-century class-consciousness rooted in the experiences of workers grappling with how sexism, racism, and power operate under capitalism.

- Binational Gatekeeper: The Italian Government and US Border Enforcement in the 1890s

by Lauren Braun-Strumfels- While the 1891 and 1893 Immigration Acts established inspection protocols that remained in place for decades, less is known about how US agents initially translated gatekeeping laws into the durable policy directives that had a profound effect on the migration of working-class people. Before the “qualitative” restriction of specific racial, social, and economic conditions transitioned to a period of “quantitative” or enumerated exclusion by the 1920s, the US government had to establish a structure to carry out the work of exclusion, but this early era of qualitative gatekeeping is less understood. Italian encounters with federal agents at Ellis Island show how the 1891 and 1893 laws empowered the administrative state to carry out the work of exclusion shadowed by the banality of bureaucratic decision-making. The records of the short-lived Office of Labor Information and Protection for Italians (1894–99), the only outpost of a foreign government allowed to operate in the main processing building on Ellis Island, offers a rare snapshot of the gatekeeping process in its crucial early years. Given that Italians were the single largest ethnic group to be processed at Ellis Island over its sixty-two-year history and the primary target of inspectors in the station’s first decade, their experiences with bureaucratic exclusion illuminate how the United States moved to systematically control working-class migration.

We will be releasing another new essay by Jason Resnikoff from December’s issue of Labor shortly.