One of the earliest foundations of the progressive theatre movement in America was contributed by the Yiddish Theatre, 1887–1913, in the formation of the Hebrew Actors’ Union with its strong ties to socialist trade unionism in Europe. The unionization of the Yiddish actors was the genesis of “agitprop” theatre, short for “agitation propaganda” theatre for political purposes. The liberation of the sidewalks in front of the theatre to plead their cause against theatre managers gave a whole new meaning to the phrase, “staging a strike.” The term “agitprop” for this highly effective clever weapon was finally brought over from Russia in the 1920s.

Agitprop theatre, made either in the moment or rehearsed and presented by “hit and run” companies, became the heavy artillery used throughout the Great Depression to gain support for labor actions among coworkers and the general public. It made a powerful news-grabbing comeback in the 1950s and 60s in America with the debut of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, The Farmworkers’ Theater, and the Bread and Puppet Theatre of New York.

At the end of the 19th century, unionization was finding its way into the theatre as an industrial workplace. Stage carpenters, painters, costumers and stage hands had been gaining union recognition since the mid 1880s. It was long before actors in the Yiddish theatre shed their elitism as “artistes” and recognized their role in an industrial work place. Actors worked unpaid in long rehearsal periods. They had to provide their own costumes. They could be fired without warning for any reason. With inferior pay compared with their male counterparts, more expensive costumes to buy, and sexual harassment from (usually male) superiors and coworkers, the situation for female performers was worse.

Jewish actors/impresarios Thomashefsky, Mogulesko, Goldfaden, and Adler thought that actors imported from Eastern Europe and Russia could be paid less and worked harder with little recourse but to keep silent. They had not figured that Eastern European performers, steeped in European socialist trade unionism, would stand up for themselves.

The very first performing groups to unionize were the Yiddish Theatre Choristers in 1886. Due to continued concerns over wages and working conditions, the actors soon followed suit. According to Mendel Teplitzky, “The organizing of an actors’ union began in November 1887 as an act against Abraham Goldfaden, who at that time had taken over the Romanian Opera House [in New York]. “We picketed the theatre. Arrests were not lacking. They once arrested me” (Teplitzky 2008). In their campaign for unionization, the actors would soon discover their skills in recruiting the audience into their struggle.

In the spring of 1888, perhaps to undermine the growing interest in unionism after the Goldfaden incident, Jacob P. Adler took his company out of the Lower East Side of New York and moved it to Chicago. Adler confessed that things did not go well. “Bitterness began. Anger began. In the end, the actors declared an actual strike—the first strike, if I am not mistaken, of Yiddish actors in America . . . This meant couplets insulting our rivals sung before the audience in the middle of the play” (Adler 1999). What he is describing is a theatrical guerrilla action in front of an audience. For the first time, the performers used the opportunity to agitate for their grievances directly from the stage within a performance event, generating impromptu material with a political purpose that had nothing to do with the play they were performing. This was the first recorded instance of “agitprop” theatrical activity to support a “wildcat” strike.

Adler’s Chicago experiment was a financial disaster. Adler and the company returned to New York, but using the stage as an organizing tool became part of the actors’ political arsenal. The next step followed soon thereafter. “The Hebrew Actors’ Union (HAU) was founded in 1888, making it the first theatrical union founded in the United States with a peak membership of 400 members.” Then:

“In 1889, the lesser actors were earning too little to live on. … Zilberman, the owner of Poole’s [Theatre] fired all the actors and choristers in the union and replaced them with non-union workers, which led to a strike. … All the striking theater workers rented the Oriental and started a cooperative theater under the leadership of the UHT [United Hebrew Trades] … The cooperative theatre lasted only a short while… The Poole’s strike was lost, but the Actors Union lasted a long time” (Weinstein 2018).

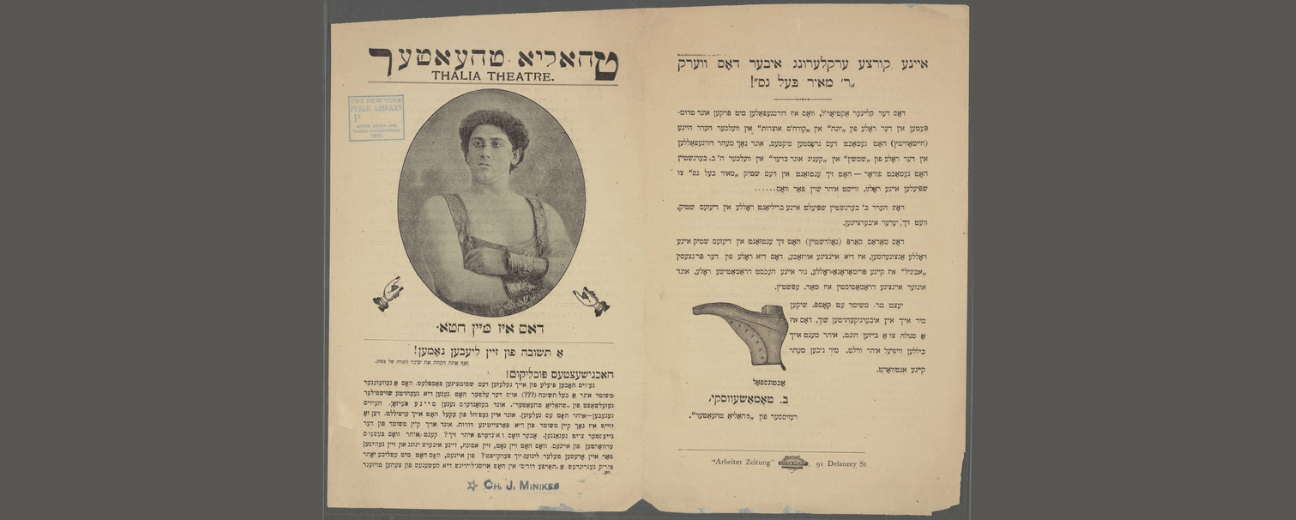

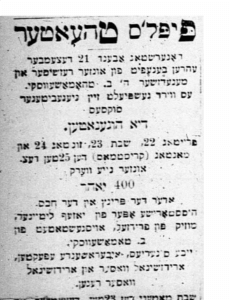

The members elected officers and maintained the union between strikes, but things did not settle down. The December 19, 1899 issue of Forverts carried an announcement that “400 Years = 400 יאהר.” The “new work” by B. Thomashefsky would be performed at the People’s Theater on Friday December 22, Saturday the 23rd, Sunday the 24th, and Monday the 25th (Christmas Day), 1899. This production did not run smoothly. All of the issues came to a head.

A bald-faced attempt by the producer to skirt his obligations to the Choristers Union raised the stakes. The director of the play, Boris Thomashefsky, decided that the recognized actors—Leibush Gold, Leiser Goldstein, Solomon Mane, and Efraim Perlmutter—should sing in a chorus as a quartet. Singing in the shows was strictly reserved by contract for the choristers. By asking the actors to sing, Thomashefsky was attempting to avoid hiring and paying choristers. In support of the choristers, the actors walked out. “The owners continued to perform [produced the show] with several Yiddish actors that they brought from the Province [Theatre] and there broke out a large strike with strike-breakers” (Mlotek 2008). “The owners of the theatre thereupon declared a lockout against the four protesters and the whole troupe left the rehearsal” (Mlotek 2008).

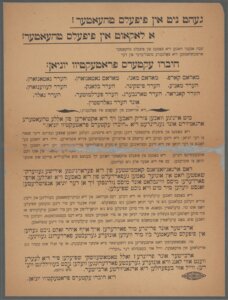

A struggle of nearly six weeks ensued. Insulting, inflammatory broadsides were plastered on lampposts, fences, and in the newspapers. A poster from this strike is preserved, declaring a boycott of the theatre. These were a kind of “agitprop-in-print.” In part, it says:

“GEHT NIT IN PIPELS THEATER! (Don’t go to the People’s Theatre!) A lookout at the People’s Theatre! Saturday night the bosses of the People’s Theatre locked out the following members of the Hebrew Actors’ Protective Union: … Workers and friends, we implore you not to go to the People’s Theatre until we achieve our demands… Thomashefsky should perform before empty walls as long as our just demands are not granted as commanded by the organized workers” (Hibru Eḳṭers Proteḳṭiṿ Yunyon 1899).

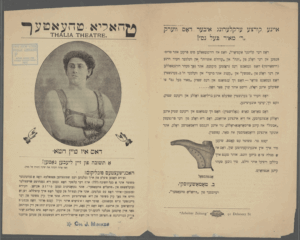

A broadside with Thomashefsky’s rebuttal to the strike complaint also exists. Evidently, this was a common form of exchange. It was only a short evolutionary leap to the tactic of striking actors standing outside a theatre or invading a lobby, making a commotion with a “guerrilla action” speech or a skit, then beating it out the door.

After a protracted struggle the HAU was chartered by the Yiddish United Trades Council. A contract agreement recognizing the union as the representative for the actors with this theatre was signed on December 31, 1899. The union had won recognition, but the struggle was not over. The following notice appeared in the Forverts of New Years Day, 1900, under the title, “Distress of the Yiddish Actors”:

“Apparently, trouble—physical blows—ensued at the People’s Theater on December 28, which were aimed by the theater “managers” at the actor, “Goldstein.” [Goldstein was one of the actors asked to sing in place of the choristers by Thomashefsky] The managers also dismissed Goldstein after this blow up. In retaliation for this incident, other performers said that they would also not perform on that day [December 28, 1899]. The managers said that they were prepared to pay $100 to make good on their bad behavior. As a direct result of this incident, 45 actors from three Yiddish theaters formed the ‘Hebrew Actors’ Protective Union.'”

Clearly, the actors’ tsuris was not over. An ad posted in Forverts from January 8 to 18, 1900, crowed about the show’s continued success, clearly indicating that the lockout was ongoing. From the month of January 1900, Schiller discovered a megillah of twenty-four articles in Forverts (January 1-31, 1900) documenting a continuing melodrama being played out in the entire Jewish community caught in the throes of the struggle for the union. A few examples:

“The Demands of the Actors.” January 23.

“Bakers Union 163 of Brooklyn Regular Meeting Detained.” January 23.

“In Sympathy with the Actors.” January 24.

“No Change in the Condition of the Actors’ Strike.” January 28.

Friedlander, Max. “United Jewish Trade Unions of New York State.” January 29.

“The Actors’ Fight.” January 29.

“Public Opinion. About the Actors’ Strike.” January 30.

“Public Opinion About the People’s Theater—Resolution.” January 31.

In the middle of this Sturm und Drang, an article in the New York Sun from January 4, 1900 reported a most interesting turn of events. It noted, “The recently organized Hebrew Actor’s Union, which asserted itself last week by delaying the performance at an East Side theatre for fifteen minutes, came out yesterday with a manifesto in Yiddish” [emphasis mine]. This could only have been another guerrilla theatre action by the locked-out actors. On January 3, they must have invaded the theatre, jumped up on the stage, or held forth in the lobby in a guerrilla-style appropriation of the performance space before the show began.

Then, miracle of miracles, Thomashefsky had a change of heart. Most likely, his epiphany was caused by his losing money due to the boycott of the show. “After a few weeks, Thomashefsky recognized the union and the strike ended” (YIVO Institute for Jewish Research 2006). Twenty-three Yiddish theatres across the country signed with the union to employ its members, setting an example to other performers’ groups. The lessons learned from their power to persuade returned to the stage of history in the Actors’ Equity strike of 1919.

The content of this article is taken from Dr. Joel Eis’ and Doug Rippey’s manuscript, Left Off the Program: The Untold Story of Progressive Theatre in America Before WWII [working title] currently circulating for publication.

Source Notes

Adler, Jacob. 1999. A Life on the Stage: A Memoir, Translated, Edited, and with Commentary by Lula Rosenfeld. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Forverts. 1900a. “The Actors’ Fight.” Translated by Riva Schiller. January 29, 1.

Forverts. 1900b. “Bakers Union 163 of Brooklyn Regular meeting detained,” Translated by Riva Schiller. January 23, 1

Forverts. 1900c. “The Demands of the Actors.” Translated by Riva Schiller. January 23, 1.

Forverts. 1900d. “In Sympathy with the Actors.” Translated by Riva Schiller. January 24,

Forverts. 1900e. “No Change in the Condition of the Actors’ Strike.” Translated by Riva Schiller. January 28, 1.

Forverts. 1900f. “Public Opinion. About the Actors’ Strike.” Translated by Riva Schiller. January 30, 2.

Forverts. 1900g. “Public Opinion About the People’s Theater—Resolution.” Translated by Riva Schiller. January 31, 2.

Friedlander, Max. 1900. “United Jewish Trade Unions of New York State.” Translated by Riva Schiller. Forverts. January 29, 2

Hibru Eḳṭers Proteḳṭiṿ Yunyon. 1899. “Geht nit in Pipels Theater!” (Don’t go to the People’s Theatre!), Dorot Jewish Division, Thomashefsky Collection, Poster No. 182. The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/af248170- 2122-0134-4d06-00505686a51c?canvasIndex=0

Sun (New York). 1900. “Jewish Actors Mean Fight: But So Do the Managers, so Trouble Is to Be Confidently Expected.” January 4. Library of Congress. Chronicling America. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83030272/1900-01-04/ed-1/

Teplitzky, Mendel in Chana Mlotek. 2008. “Notes on The Hebrew Actors’ Union” (Der yidisher aktyorn-yunyon). Translation from various unspecified sources. Email message to: Fruma Mohrer, Ettie Goldwasser, and Fern Kant. November 24, 2:22 p.m.

Thomashefsky, Boris. 1900. “Dos iz mayn ḥet: a tshuve fun zayn lieben nomen.” Thalia Theatre. Dorot Jewish Division, Yiddish Theater Posters, no. 228. The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/04cdc2a0-c933-0133-8ffc- 00505686a51c

Weinstein, Bernard. 2018. The Jewish Unions in America: Pages of History and Memories. Translated and annotated with an introduction by Maurice Wolfthal. New York: Open Book Publishers. Accessed November 24, 2025. https://www.openbookpublishers.com/books/10.11647/obp.0118.

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. 2006. “Records of the Hebrew Actors’ Union [Historical note]” RG 1843. Center for Jewish History. Accessed November 24, 2025.https://archives.cjh.org/repositories/7/resources/554

Zilbercweig, Zalmen and Jacob Mestel, eds. 1934. Leksikon fun Yidishn Teater, vol. 3. Mexico City.

Authors

-

Dr. Joel D. Eis has been a professional designer and teacher. He has spent the majority of his career in progressive and radical theatre. He organized agitprop theatre performances during the strike for the first Ethnic Studies Program in America at San Francisco State University in 1968 and joined the grape strike-based Farmworkers’ Theater. He was an organizer for the Bay Area Theatre Workers Union in 1981. Eis has had a professionally published textbook on stagecraft and four books on theatre and politics, including a memoir, Standin' in a Hard Rain: the Making of a Revolutionary Life with World Beyond War Press in 2023. He and his wife, Toni, own and run the Rebound Bookstore in San Rafael, California, where leftist groups and banned books clubs meet. This article is taken from notes for his latest book on labor theatre, Left off the Program: The Untold Story of Progressive Theatre in America before WWII.

-

Doug Rippey was a member of El Teatro Campesino (The Farmworkers’ Theater) from 1967 to 1968 as an actor, musician and technician. He has been a member of Colorado’s Romero Theater Troupe since 2009, promoting “Social Justice Through Organic Theater.” He has been doing labor support research and investigations since 1966. As a legal worker, he first joined the National Lawyers Guild in 1970 and was formerly a licensed private investigator. He holds a library and information science graduate degree and recently retired after working in a variety of libraries and archives for 40 years.