The Hollywood Movie Norma Rae defined working class women’s experiences in the wake of neoliberalism. The film launched Sally Field into a cultural icon, but according to Aimee Loiselle’s new book, it warped the labor history that was the base for that story–the Puerto Rican and southern white women whose struggles were framed by a dissident culture. In her new book, Loiselle tells the story in a way that shows workers actively attempting to intervene in cultural production. Historian Anne S. Macpherson interviewed her on her key findings.

The “American working class” and who can stake a claim to that term has again become a flashpoint in politics, with serious implications for immigration, education, trade, and public works policies. What can your book, with its emphasis on both the multi-racial, trans-colonial working class and the cultural formation of power via popular representations of workers, teach us for organizing and politics today?

One message I hope readers take from the book is the significance of the constant interaction between cultural and economic structures. A second and related lesson is that building and rebuilding a labor movement with links to all workers, in as many job areas as possible, can cultivate political-economic leverage only with attention to their issues of gender, race, and im/migration and with intensive efforts in mainstream popular (as well as labor movement) culture.

It is imperative to recognize that cultural structures are more than a zeitgeist or mentalité (which are useful concepts but do not function in the same way). Cultural structures are embedded within the larger functions of society. Structures of feeling, for example, grow from repeated interactions between texts, related activities, and the audiences when people experience regular reiterations of affective response mingled with ideas, concepts, and points of view. Affective associations across a society arise with varying levels of intention, and such recurring emotional dynamics can align cognitive, mental, and social habits with a certain political and economic composition. As these become entwined, they serve larger cultural formations, which generate meanings, notions, customs, and sensations that converge over time to legitimate a given distribution of power. Entrenched cultural formations, such as the neoliberal individualism I conceptualize, are powerful sets of these structures that interact consistently with political-economic practices. So mainstream popular culture, the most pervasive and widespread media and performances, is a highly contested arena that impacts not only the way society perceives economic relations, but also the unfolding of economic relations.

A certain structure of feeling – a multifarious knot of affect, beliefs, and values – bound up with a notion of the white industrial masculine working class has dominated US politics and shaped access to government representatives and to wages, safety, resources, and citizenship documents even as legislation, colonial policy, and international trade agreements explicitly address the existence of women and men workers of diverse race, ethnicity, age, and citizenship across a variety of occupations. These have included manufacturing and mining, but also farming, cleaning, nursing, data entry, and daycare (to name a few). Although economic systems are crucial to daily living and governance, cultural formations, with narratives and meanings bound to emotions, often have more power than material evidence for determining the distribution and retention of financial resources and for directing voters’ allegiance and political action. In this political-economic-social-cultural spiral, culture is not a distracting superstructure. It is a mutually constitutive component of people’s existence and interactions with all parts of society. Many organizers imagine pop culture efforts as an extra, something to do when they might have the time or money, but the arena of culture is crucial to all their employer/work condition demands and political/legislative campaigns. (I am clearly not a syndicalist and advocate a combination of organizing, collective bargaining, electoral politics, legislative agendas and lobbying, media campaigns, and direct actions – the whole package of power building.)

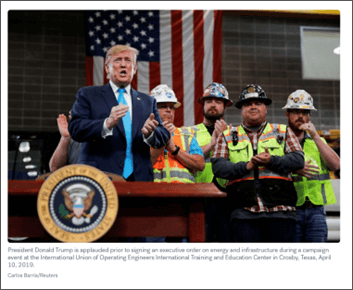

Activists in the US labor movement have had some success at creating movement culture, especially with Popular Front novels and plays (Michael Denning argued these reached beyond leftists of the 1930s, and I argue they inspired Martin Ritt, director of Norma Rae) and with Black gospel and folk music during the 1950s and 1960s. They have been less successful fighting in the arena of big popular culture. Trump, on the other hand, who we know has never been working class and has repeatedly underpaid or taken resources from workers, has mobilized the dominant structure of feeling bound with the notion of a white industrial masculine American working class to help gain and wield power. (He is building on and amplifying tactics used by Nixon and Reagan, but not enough time to discuss that here.)

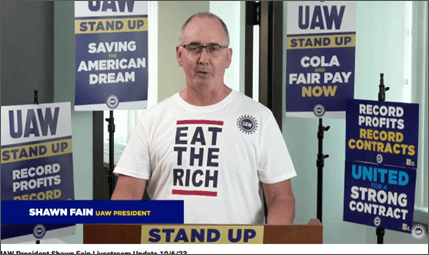

Shawn Fain of the United Auto Workers (UAW) became a strong individual presence in labor movement culture with his “Eat the Rich” t-shirt and “corporate greed” narrative. He was even able to break into mainstream news coverage during the 2023 coordinated strike wave. Fain still has not, however, gotten any traction in big popular culture. When Christian Smalls was president of Amazon Labor Union and courted pop coverage in 2022-23, “union drip” earned mainstream notice in magazines like Elle but did not maintain pop circulation. When Fain or a particular union becomes a regularly impersonated character or group on Saturday Night Live, the labor movement is forming power through culture.

You are a labor historian who studies women in manufacturing, but the book also examines a major blockbuster movie and television references. How would you describe the fields of history this book is in conversation with?

I am a labor historian first and foremost, and Beyond Norma Rae is a labor history of Puerto Rican and southern white women and their fights for better working conditions, for influence over the terms of globalization, and for control of the popular representations of their work and unionizing.

Because there is a movie in the title and the core of the book tells the history of Crystal Lee Sutton’s struggles with a movie production about her life, many people want to categorize the book as “cultural history.” I value their attention and comments for sure, but resist that inclination. Beyond Norma Rae prioritizes the labor histories of women in home goods, apparel, and textile manufacturing as the industry served US global ambitions and disaggregated production in the twentieth century. It then analyzes the movie Norma Rae (1979) as a site of class conflict, not as a representative text. In this case, my concern was not the movie production as a worksite for staff, crews, and actors, e.g. J.E. Smyth’s Nobody’s Girl Friday: The Women Who Ran Hollywood (2018). I studied the “Crystal Lee”/Norma Rae movie production as a site of class conflict over popular culture and who has the power, the assets and connections, to determine major representations of work and unionizing. My interest in the movie, therefore, is about labor history, about who gets to contribute to mainstream meanings and perceptions of the “American working class.” I align with scholars who argue that material conditions, such as hours of labor or wages, do not unilaterally determine who gets validation as “workers” or the “American working class.” This social and cultural legitimation shapes legislation, policies, oversight, and practices. And these, in turn, influence material conditions.

Immigrant farmworkers are an example of this reality. In general US society, particularly in broad public debates about work and wages, immigrant farmworkers are not imagined as part of the “American working class.” (Even scholars of agricultural history often have to assert the importance of farmworkers within labor history.) The same is true of Puerto Rican needleworkers and southern Black union activists. Cultural structures have serious material consequences and vice versa. And I think the current expulsion of tens of thousands of federal workers resulted from a convergence of the “American working class” cultural structure with the neoliberal narrative “government is the problem” serve right-wing Trumpist ambitions to dismantle the federal government.

I greatly appreciate histories of working-class culture, including Michael Denning’s foundational book The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (1996) and Nan Enstad’s Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure: Working Women, Popular Culture, and Labor Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century (1999). My book, however, is not a study of working-class or labor movement culture. It is a study of working-class women, Crystal Lee Sutton and Gloria Maldonado, fighting in popular culture as a contested field of production because they are union activists who understand both the power of culture and forming power through culture.

Even though the book is constructed as a labor history, it uses approaches and tools from women’s and gender studies, business history, cultural history, and history of capitalism. I have always been drawn to the inherent interdisciplinarity of history – long before I knew that term.

The movie Norma Rae (1979) is well known in the United States and has even been screened by labor unions. What do you most want Americans, especially American workers, to understand about the movie, and what does it mean to go “beyond” Norma Rae?

For scholars and writers, I want them to understand that Norma Rae and other Hollywood movies are not reflections or mirrors of society. Hollywood realism works hard to hide the means of production and to lead audiences into the perception that they are neutral observers of a “real” story. Even respected historians have an inclination to read movies as straightforward representations of a time period without acknowledging they are massive, contested culture industry productions with layers of agents, lawyers, accountants, screenwriters, creative professionals, crews, and advertising teams as well as directors and actors. Experts and people with special backgrounds are also consulted about dialogue, sets, and costumes.

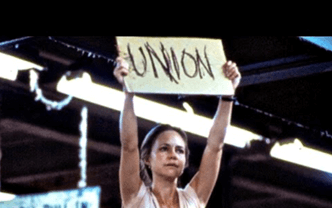

I also hope people come to see that Norma Rae is a key player in mainstream cultural understandings of workers and of defiance. The icon it generated still circulates through big pop culture, in streaming television shows and social media posts. The visual component of the icon displays Field as Norma holding a UNION sign overhead with the camera only on her. Fellow union members, allies, coworkers, and neighbors have been cropped out, and since the movie does not contain any reference to the sixteen-year campaign against J.P. Stevens, or the longer history of southern labor activism, neither does the icon. Norma Rae stands alone in her rebellion. The linguistic component appears as phrases like “having a Norma Rae moment,” which express the icon’s essence: a transitory individualist defiance. The repeated visual and linguistic representation of rebellion without ideology, movement, or even context allows the icon to work on behalf of different types of defiance, for different desires and purposes.

Of course, movies are not perfectly coherent texts. Different viewers might see potential for actions beyond what appears on screen; others might bring their knowledge of unions or collective organizing. Viewers might read Norma’s individual rebelliousness in ways that draw them toward complex political, sociological, and economic issues rather than away, and the moment of defiance might prompt a viewer to look into unionizing. For the great majority of audiences, however, the fully extracted and refined icon does little to raise any awareness of collective working-class action by Black and white factory workers in the US South.

Going beyond Norma Rae means diving into that deeper history, particularly the history of Puerto Rican needleworkers who moved through the industry at the same time as Sutton and southern workers. It means engaging these histories as the counter-narrative to the movie and its appropriation and obscuring of the collective labor movement and multi-racial workers who made it possible. Going beyond Norma Rae means also exposing the financial instruments and legal maneuvering used to marginalize and eliminate Sutton from the creative decisions and revenue for a film production based on her life.

Early in the book you analyze the history of the textile and garment industries in a region you call the “US Atlantic.” How do you define that region, and how were workers connected across it?

The concept of the “US Atlantic” was a direct result of the archives. Documents from the textile and apparel industry and from unions like the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA) showed executives, investors, politicians, and national union leaders making arrangements and taking action across the three regions – the Northeast, South, and Caribbean – as interconnected investment and manufacturing sites. The first discovery was in the folders for the Charleston Inter-State and West Indian Exposition of 1901-02, where I found that businessmen, investors, apparel contractors, trade ambassadors, and politicians envisioned and reinforced links throughout the Northeast, South, and Caribbean. Rather than rigidly separated or sequential geographies, these spaces were differentiated yet interconnected investment and manufacturing areas with simultaneous labor markets demarcated by race, ethnicity, and citizenship.

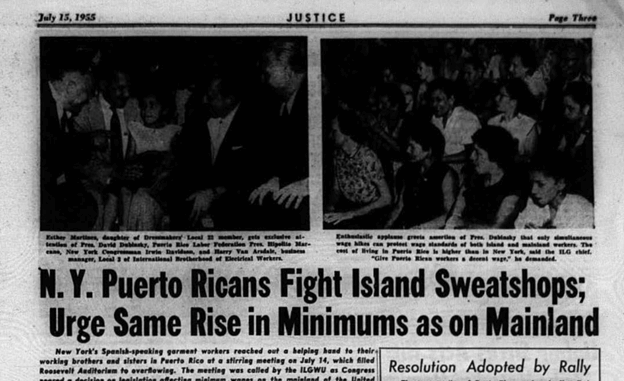

Workers, in pursuit of better conditions, wages, and quality of life, understood the places as interconnected as well. In 1933, Puerto Rican women went on strike in multiple cities across the main island when the Depression caused wage reductions in the South that drove piece rates down for Puerto Rican needleworkers. And women from Puerto Rico moved to the Northeast for better wages and housing even as northeastern managers redistributed manufacturing throughout the US Atlantic region depending on cost analyses that included real estate, taxes, wages, tariffs, and shipping. The ILGWU was particularly active from the Northeast to Puerto Rico, with organizers and members who traveled back and forth. In its newspaper, Justice, I found a 1955 article about Puerto Rican members in New York City protesting the lower wage in Puerto Rico. They challenged the differentiation not only as unfair, but also as a systemic means for lowering all wages.

The US Atlantic concept is not in any way a rationale for the occupation of Puerto Rico. It is a means for revising US labor history to include Puerto Rican women; for complicating the history of the textile, apparel, and home good industry and the workers and their unions; and for intervening in the history of neoliberal political economy, specifically regarding export processing zones/special economic zones (EPZ/SEZs) that have come to dominate global manufacturing and have roots in what I call “colonial industrialization.”

As a historian of the Caribbean including Puerto Rico, I was heartened to see Puerto Rico and Puerto Rican women workers at the forefront of the book. Why is it important to you to center their experiences and thus the business and labor dynamics of US imperialism in Puerto Rico and through Puerto Rican migration?

I am honored – and a bit relieved too – when historians of Puerto Rico appreciate this work. I center Puerto Rico because it served (and still serves) as a critical component in manufacturing and finance arrangements within larger US imperialism and should be studied as part of US labor history. My research and arguments are not supportive of any view that Puerto Rico is a justifiable colony of the United States, and I stand with and build upon the research of Puerto Rican Studies scholars, including Blanca Silvestrini, María del Carmen Baerga, Altagracia Ortiz, Carmen Whalen, and Eileen Findlay.

US labor history has been infused with divisions of geography that do not always serve the field well. Deep targeted research projects, such as Jarod Roll’s Poor Man’s Fortune: White Working-Class Conservatism in American Metal Mining, 1850–1950 (2020), make notable contributions. Requiring all scholarship to have firm geographic boundaries, however, can serve the very efforts at segmentation and invisibility that political and corporate leaders used to maximize their control over flexible global options.

Some divisions have softened with frameworks like intersectionality, transnationalism, and global capitalism, yet a few scholars questioned my decision to include Puerto Rican and southern women in the same book. When I mentioned the archival evidence from the Charleston Exposition and ILGWU, some would concede it was acceptable to include both. I see alignment of my work with historians like Julie Greene, Colleen Woods, Reena Goldthree, and Kornel Chang who push against and across national-colonial divides as well.

The book also joins those scholars who argue that manufacturing did not relocate in a direct line from the Northeast to the South to the Global South, but rather was redistributed and shifted across all these geographic spaces via labor, real estate, and shipping arbitrage that sought the highest return on investment and lowest costs in any combination. By 1900, Puerto Rico as well as the New South were primary sites for developing these practices as corporations worked to hone their financial, technological, and bureaucratic tactics. The practices in Puerto Rico became a template for the 1965 Border Industrialization Program/maquiladoras and EPZs.

How important have popular media and culture silences and distortions been in the ultimate collapse of the U.S. textile and apparel industry through international trade agreements and neoliberal federal laws? Or are they both symptoms of a common cause?

In my current project, I am studying the cultural-economic power of hip-hop fashion brands such as Baby Phat, so I am developing an argument that the textile and apparel industry disaggregated manufacturing, which eroded stable domestic jobs and unions. But it retained and expanded other aspects of the industry in the United States. The parts of the industry that remain are the brand management and marketing of apparel and accessories and the financial management of returns on investment, public securities, and private equity. While the movement of labor, capital, and products is global, the hub for hip-hop fashion companies often remains in the United States. There are design, merchandizing, and office workers, in much smaller numbers of course, who do their jobs in urban centers like New York City and Atlanta. One of my arguments is that the quantity of workers is not necessarily an indicator of their necessity or significance to an industry, and I am interested in the role of financialization in labor conditions.

That said, popular media and culture silences and distortions served the disaggregation of manufacturing and the intensified domestic collapse during the 1980s and 1990s. Economic systems depend on and reconstitute gender, racial, ethnic, and citizenship divisions. The details of any business implementation rely on these differentiations, so the convergence of political-economic-social-cultural structures in a particular time period is neither inevitable nor random. When the neoliberal federal laws hit, colonial industrialization and bilateral trade agreements had been restructuring the industry for decades. In general, this dispersal of production relied on imperial narratives of helping the Other and on the invisibility of women of color in popular understandings of manufacturing and the American working class. In business plans and trade agreements, the dispersal relied on the naturalizing of women’s lowest-wage sewing labor as feminine and traditional and the celebration of export processing work as helping their poor backward families. This is why Maldonado fought for her stories to be told her way – she hoped people would know the collective struggle. She joined generations of women of color and low-wage women workers in articulating an American working class that encompasses women of many races, ethnicities, and citizenships who are mobile, hardworking, organized, and connected to the world.

Authors

-

Prof. Anne S. Macpherson is Professor of History at SUNY-Brockport with a specialization in Latin American and Caribbean HIstory. Among her publications are From Colony to Nation: Women Activists and the Gendering of Politics in Belize, 1912-82 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007)“Birth of the U.S. Colonial Minimum Wage: The Struggle over the Fair Labor Standards Act in Puerto Rico, 1938-1941,” Journal of American History 104:3 (December 2017)

-