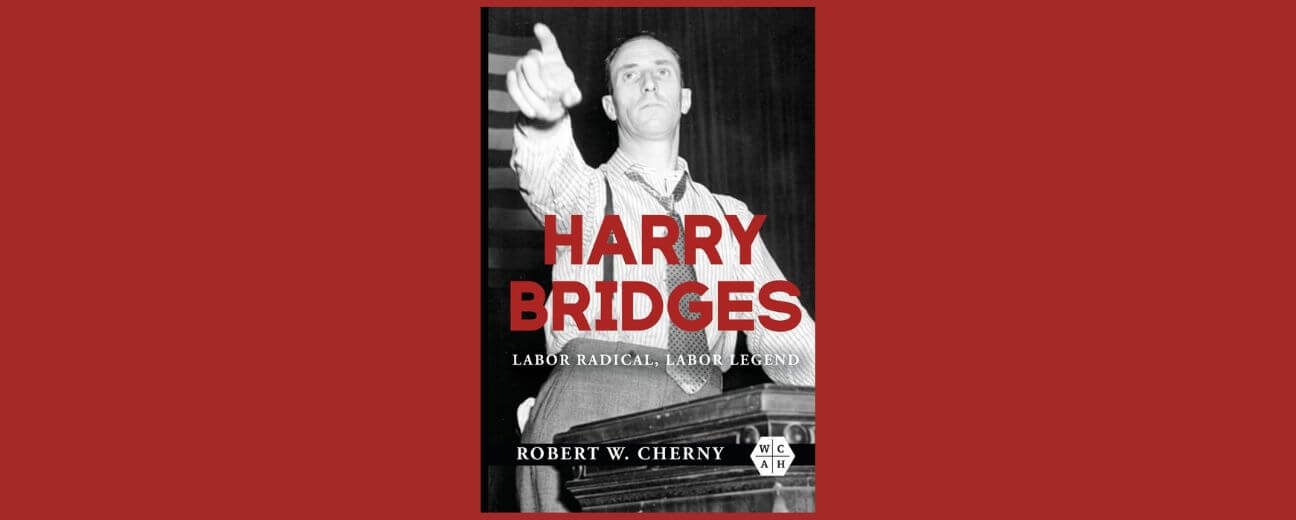

Robert W. Cherny’s new book, Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend (University of Illinois Press, 2023) is a monumental achievement. More than thirty-five years in the making, it is exhaustively researched, gracefully written, and comprehensive. The late Charles P. Larrowe’s Harry Bridges: The Rise and Fall of Radical Labor in the U.S. has served honorably as a basic biography of Bridges since its publication in 1972. Still, with all due respect to Larrowe’s earlier work, Cherny’s 478-page volume is now the definitive story of the ILWU founder, forty-year ILWU president, and towering figure in American labor history. If, as a member of the ILWU or as a non-member interested in labor’s past, you want to learn about the iconic Bridges in depth and detail—who he was, what he did, and why he mattered so much—this is the book for you. The new Harry Bridges also provides a working knowledge of the history of the union’s core entity, the Longshore Division, from its beginnings in the 1930s through Bridges’s retirement in the 1970s.

In 1985, the retired ILWU leader and his wife Nikki approached Cherny about writing Bridges’s biography. As Cherny notes in his acknowledgments, his research took him “from Harvard to Honolulu, from Moscow to Melbourne.” He carefully examined countless documents in the ILWU library and in places that other researchers have overlooked or lacked access to, including Bridges’s papers at San Francisco State University, enormous FBI files (for years the Bureau monitored everything Bridges did), and hard-to-reach archival materials in Russia. The book’s rich and highly informative backnotes alone are nearly a hundred pages long.

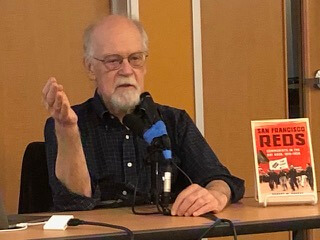

During his forty-two-year academic career at San Francisco State, Cherny was active in his faculty union and served at various times as director of labor studies, chair of the history department and the academic senate, and acting dean of undergraduate studies and of social sciences. He also wrote or co-authored six other books and forty scholarly articles, and he co-edited anthologies and textbooks. But the long wait for the appearance of this magisterial biography, first conceived thirty-five years ago, was worth it.

Cherny’s text consists of eighteen mostly chronological chapters detailing with meticulous care many familiar events in Bridges’s and the union’s history. Two early chapters follow Bridges’s life from his birth in Melbourne in 1901 through his youth in Australia, where he was influenced by his activist uncle and by that nation’s union movement. We learn how he became a seaman on sailing vessels, came ashore in San Francisco in 1922, and, through the early Great Depression years of the 1930s, labored there as a longshoreman in appalling non-union conditions characterized by corrupt hiring practices, heavy and dangerous work, brutal “speed-ups,” and other abuses.

Three key chapters recount Bridges’s leading role in organizing the Pacific Coast Branch of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), sometimes with the help and participation of Communist Party members, and his critical leadership in the 1934 West Coast maritime and San Francisco general strikes. Cherny vividly describes the events of Thursday, July 5, 1934, when San Francisco police killed strike supporters Nicholas Bordoise and Howard Sperry. “Bloody Thursday” sparked the July 16-19 San Francisco general strike in protest that was an important turning point in the maritime struggle.

During this early period, under the guidance of Bridges and his allies, the union’s patented progressive character emerged, featuring support for union democracy, equal access to jobs, and, as outlined in their mimeographed organizing newspaper, the Waterfront Worker (October 1933), non-discrimination on the basis of “creed, color, or political beliefs.” Two chapters trace important developments in the six years following the momentous events of 1934, including Bridges’s 1935 search for unity with other marine and transportation unions and his part in his organization’s leaving the ILA and founding the ILWU in 1937.

Cherny then departs somewhat from this chronological story to evaluate Bridges’s early relationship to the Communist Party. Four of the succeeding ten chapters describe the unscrupulous and ultimately unsuccessful efforts between 1934 and 1955 of vigilantes, police agents, reactionary politicians, conservative operatives, and federal authorities to deport Bridges, who they alleged was a Communist Party member.

Subsequent chapters cover main currents in Bridges’s and the union’s post-World War II experience. These highlight the 1948 longshore strike, which Cherny characterizes as a struggle to retain the union-controlled hiring hall that had been won in 1934 and to preserve Bridges’s position as ILWU president from red-baiting employer attacks; the Mechanization and Modernization (M&M) contracts of 1960 and 1966 that paved the way for the container revolution in waterfront work; the long 1971 coastwide longshore walkout; and Bridges’s retirement in 1977 and death in 1990.

As Cherny notes in his preface, Harry Bridges does not contain extensive material on the warehouse organizing drive in the 1930s and the sugar and pineapple campaigns in Hawaii of the 1940s, which, he emphasizes, are fully covered in other books. Harry Bridges, the ILA and 1934, and the first forty years of the ILWU Longshore Division were sufficient challenges for one long volume. Still, Cherny provides enough detail about these other topics to keep readers oriented.

Bridges acted as a radical in sanctioning job actions, or quickie strikes, and resisting arbitration; after 1935, though, Bridges began to favor institutionalized arbitration as the best way to enforce the longshore contract.

Cherny offers several intriguing observations that follow from his many years of study. He contends that during the first few years of waterfront leadership, Bridges acted as a radical in sanctioning job actions, or quickie strikes, and resisting arbitration; after 1935, though, Bridges began to favor institutionalized arbitration as the best way to enforce the longshore contract. In 1934 Bridges insisted on an end to the abusive hiring practices of the non-union era through a worker-controlled hiring hall system, and on a coastwide longshore contract to keep employers from playing ports against each other—radical demands for their time. But during the six years after 1934, Cherny argues, Bridges helped bring stability to the waterfront by embracing arbitration. The capstone of this evolution in Bridges’s thinking was a new arbitration provision in the 1940 longshore contract that provided for the immediate settling of conflicts. This system became a fixture of subsequent ILWU waterfront contracts and, Cherny asserts, is unique in the history of American labor relations.

Cherny carefully compares Bridges’s actions and policy decisions over time to numerous Communist party positions, concluding that no one from the party ever gave Bridges an order and that Bridges was an entirely independent actor who always put the interests of his union first.

Bridges’s relationship to the Communist Party receives thoughtful treatment. For at least four decades, the question of whether Bridges belonged to the party attracted the attention of scholars, writers, newspaper publishers, an assortment of enemies of the union, and government investigators. As is well documented, Bridges accepted aid from the party for his struggling union movement during 1933-1934, when there was little help available elsewhere. While Bridges openly admired the Soviet experiment in Russia, however, he always denied being a party member. Cherny carefully compares Bridges’s actions and policy decisions over time to numerous Communist party positions, concluding that no one from the party ever gave Bridges an order and that Bridges was an entirely independent actor who always put the interests of his union first. Despite the long history of the allegation that Bridges was a party member, in the end, Cherny argues, the issue is not “the most important story about Harry Bridges. The most important story is that he was a remarkably effective leader of a remarkable union.” Cherny systematically defends this claim throughout his book.

These contracts made concessions to both sides: they protected the interests of existing longshore workers and offered early retirement inducements, but they also meant that the waterfront labor force would eventually shrink dramatically.

Yet another important topic Cherny explores is Bridges’s response to automation on the waterfront in the form of containerization. In a 1938 speech at the University of Washington, Bridges famously declared that “our policy is one of class struggle. We have nothing in common with our employers. There’ll be a time when there aren’t any employing classes any more.” But Bridges’s thinking, Cherny argues, combined this Marxist philosophy with pragmatic realism. This pragmatic side influenced his handling of the 1960s M&M contracts, which ushered in containerization without a fight and which remain controversial to this day. These contracts made concessions to both sides: they protected the interests of existing longshore workers and offered early retirement inducements, but they also meant that the waterfront labor force would eventually shrink dramatically.

The long-time ILWU president even held that the advent of steady jobs in the second M&M contract of 1966 was not such a bad thing, although some have argued that separating one group of workers from the traditional hiring hall threatened the union’s cohesion.

According to Cherny, Bridges was not opposed to the elimination of the arduous job conditions he had experienced on the waterfront during his break-bulk cargo-handling days. The long-time ILWU president even held that the advent of steady jobs in the second M&M contract of 1966 was not such a bad thing, although some have argued that separating one group of workers from the traditional hiring hall threatened the union’s cohesion. Still, Bridges gained important concessions while preparing for the automation that would eventually reach the waterfront no matter what he did. Cherny ultimately concludes that “if [Bridges’s] first great accomplishment was to lead the 1934 strike that produced the hiring hall, his other great accomplishment was the M&M.”

Many are aware that Bridges briefly belonged to the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) during the fateful 1921 seamen’s strike. But did you know that he also tried to challenge Jim Crow laws in New Orleans that same year? He was only twenty years old at the time.

In addition to these major themes, Harry Bridges offers tantalizing details that may surprise even those who already know a great deal about Bridges and the ILWU. Many are aware that Bridges briefly belonged to the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) during the fateful 1921 seamen’s strike. But did you know that he also tried to challenge Jim Crow laws in New Orleans that same year? He was only twenty years old at the time. Cherny explores several other often-overlooked events in Bridges’s and the union’s past, including the shipowners’ attempt to bribe Bridges to end the 1934 strike (Bridges’s response to the messenger bearing the offer was, “I couldn’t do that, you know that, Jack”); the major 1936-37 longshore strike, which was something of a rehash of ’34 without the violence; and the relatively short 1946 waterfront walkout. The 1950 purge of the ILWU from the CIO, which the union had affiliated with in 1937, is recounted in some depth. Cherny also weaves in enough information on Bridges’s family life to provide a fully rounded picture of the long-time ILWU leader.

During his last decade in office, as employers expanded the “steady man” category and waterfront work opportunities began to decline, Cherny notes, Bridges faced some pushback from union members. He explored the possibility of merging the ILWU with either the Teamsters or the ILA, but the ILWU executive board and the union’s rank and file rejected these ideas. As Cherny reminds us, the 1971-72 strike too, at 134 days the longest longshore walkout in Pacific Coast history, was partly brought on by the long-term effects of the M&M contracts. Despite these late career controversies, when Bridges retired he was widely hailed as the hero of ’34. He was the touchstone of the ILWU then and remains so today.

——

The book contains twenty carefully selected black-and-white photos, a helpful list of abbreviations, a long bibliography, and a useful index. It should appeal to everyone interested in Harry Bridges, the history of the ILWU, and the American labor movement in general. You can order Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend from the ILWU International library or through the Powell’s Books Partnership Link, in which case 7.5 percent of your purchase will go to the ILWU Local 5 Strike Fund.

This essay was originally published in The Dispatcher.

Author

-

Harvey Schwartz is curator of the ILWU Oral History Collection at the union’s library in San Francisco. His most recent book is Labor Under Siege with Ronald E. Magden. Other books include The March Inland: Origins of the ILWU Warehouse Division, 1934-1938 (1978; rpt. ILWU 2000); Solidarity Stories: An Oral History of the ILWU (2009); and Building the Golden Gate Bridge: A Workers’ Oral History (2015). He holds a Ph.D. in history from The University of California, Davis.