Joshua Morris has published The Many Worlds of American Communism in September. Morris completed his Ph.D. at Wayne State University and teaches at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. Randi Storch asked him some questions about his purpose and findings.

While you argue for an interpretation of American communism with its different “worlds,” you also begin each chronological cluster of chapters with the political world and its considerations. How do you see individuals and Communist politics shaping the labor and community worlds you have described?

This is an aspect of American Communism that is arguably one of the most important to discuss but also the most difficult. Jacob Zumoff, when interviewed on his work on the Passaic Textile Strike of 1926, noted that when discussing the labor and community-oriented goals of communist activists, it necessarily begins with a discussion about their political ideals and understanding. This is why, in his own words, he worked to publish a piece on the links between grassroots Party activists and the international Communist movement. In other words, only by publishing his first work, US Communism and the Communist International, which focuses exclusively on communist politics, could he then bring the discussion down to the local level and talk about grassroots communist activism in the labor and community spheres.

To understand why individuals joined the American communist movement, even if they had little-to-no connection with the Party’s abstract world of idealism and the Communist International based in Moscow, one must first start with why that world of idealism and its international component appeared attractive to organizers that had various options available to them. The labor and community worlds were thus shaped and influenced by two dialectical forces: the demands and needs of the ideological core versus the practical wants and desires by American working class activists. At many times in this history, which my work seeks to highlight significantly, there is an overt and at times blindingly obvious disconnect between what Party leaders, such as William Foster and Charles Ruthenberg, desired out of their constituency and what their constituency expected out of not necessarily their leaders—but of their movement.

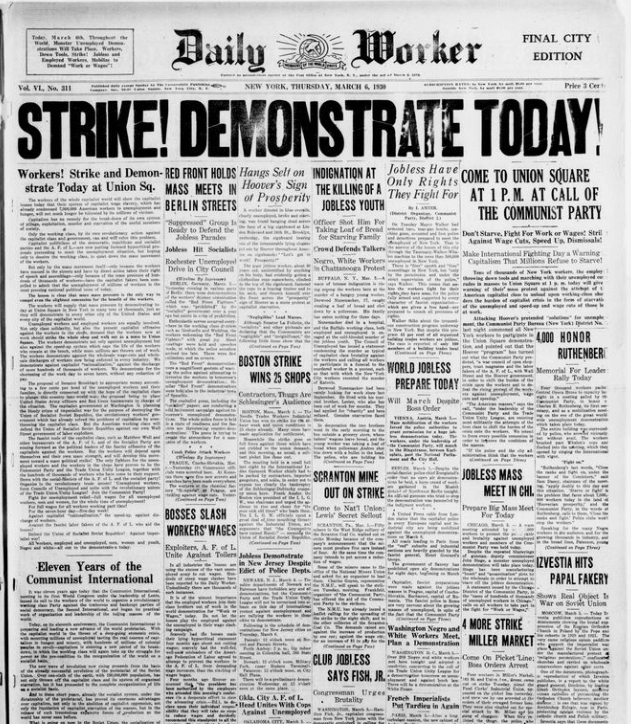

The factionalism of Party leaders in 1928 through 1929 is a prime example of what I mean. In her autobiography, Peggy Dennis noted that to the average Party member the factionalism was not only confusing it was also a turn-off. Leaders would leave New York for Moscow and would return with new titles, new duties, and some of those leaders would have been ousted. If I remember correctly, Dennis even noted how when Lovestone returned in 1928, most people in the Party did not understand his ousting and still considered him a Party leader until “corrected” in early 1929 by publications in The Daily Worker. The Passaic Strike is another key example—Albert Weisbord stepped down as a strike committee leader at the behest of the workers in the city, while the CPUSA criticized the subsequent bargaining efforts by the AFL. In each major instance of Party involvement, there is a distinction between what the Party advocated and what Party members at the grassroots defined as the limits of their activism.

Overall, I think my work tries to explain how the grassroots elements of the CPUSA typically shaped the labor and community worlds more so than CPUSA politics. The Political World formed the foundation upon which communist activism can thrive—the ideals it clung to, the identities it embraced, and the conceptualization of being part of a bigger movement than just one country’s quest for justice. This is not to displace the role of CPUSA politics—not in the least. But it is an attempt to acknowledge that CPUSA politics and CPUSA members are not the monolithic singular entity that is depicted by American Communist historiography

Who are some of the most interesting people you encountered in each of these communist worlds and how did they shape their sphere?

I met some amazing people throughout this project, which technically began in 2011 when I started gathering oral history interviews of Party members in California. Still to this day I have over 10 unpublished oral histories, including from members who lived typical American lives—not heavily active in the Party—throughout the 1960s and 70s. But if I were to narrow it down, I would have to choose three individuals specifically.

First, I met Beatrice Lumpkin in 2012 at the CPUSA’s National Convention in Chicago. I attended because I was interested in meeting new research subjects; but I did not expect to meet and land an interview with the CPUSA’s oldest living member. Lumpkin’s life story was recorded down in an autobiography for International Publishers, titled Joy in the Struggle. The most interesting aspect of Lumpkin’s life was her ongoing dedication despite what many people today in the Revolutionary Left would say is a lack of ‘praxis’. Lumpkin was no revolutionary theorist and she was not about to lead an army in the revolution; but she had everything that the CPUSA wanted in a person during the 1930s and 40s: She had dedication, she had people skills, and she understood very early on the importance of questioning authority figures. Today, her work is a testament not just to the history of American communism but also to the history of everyday American Leftists. Lumpkin not only lived through the Depression and joined the CPUSA during its peak of popularity, but she also continued to be a Party member long after the Second Red Scare had made Party membership a federal crime. Even into the 1950s, she and her husband challenged racist practices throughout Chicago as the Civil Rights movement gained momentum…all while also inviting the dangerous hand of federal prosecution in the process. Lumpkin shaped the community world of American communism by showing that it was a realm of inclusivity and a commitment to grassroots issues.

Next I met Michele Artt, who is the daughter of Carl and Helen Winter. Carl Winter was one of the 11 charged with conspiracy under the Smith Act in the 1949 Foley Square Trial, and again tried with his wife in the Michigan Six Trial of 1952/53. Artt’s oral history was a difficult one to gather, because it necessarily involved discussions about gross and at times egregious violations of civil liberties by the FBI and CIA. This included FBI surveillance of her experiences at High School prom, during her various graduation ceremonies, and during holiday times when the family gathered together. For over 15 years Artt lived under the watchful eye of the Federal Government—tax dollars spent on following her to and from school, to and from church, and to and from various Civil Rights meetings. Overall, Artt’s story was one of the darker periods of Cold War hostilities…where civil liberties were always in flux based on the circumstances of the situation. Though Artt was not a major central feature of my work, her oral history was monumental in terms of framing and setting the stage of FBI surveillance and anticommunist tactics subsequent to World War II. Artt grew up in the political world, but after it had been broken down and diffused by the grassroots membership from 1946 – 1957.

The most interesting person I met was by far Mr. M; who I must refer to as since he requested in his interviews that he remain anonymous. Mr. M was a lawyer who joined the CPUSA after his experiences fighting in World War II. As an Army air corps engineer, he was tasked with building airstrips for the Marines while island hopping through the Pacific, first at Guadalcanal, then onto Layte, then onto Manilla. During his assignment, he was given control of all-African American units of engineers. Despite growing up in Jim Crow Louisiana, Mr. M said that he came to develop a level of respect with his non-White comrades that was difficult for him to imagine occurring under different conditions. During Operation Magic Carpet, to bring the troops home, Mr. M had an experience that I’ll never forget hearing about. During a stop in Memphis to exchange trains, Mr. M was told by station staff that his African American troops would not be served meal or coffee because they were Black. Refusing to accept the situation, Mr. M told the store that he would accept full blame for ordering his men to break everything in the store. Quickly, they were all served their meals and when he got back to Louisiana, Mr. M joined the CPUSA at his college campus. For the subsequent 3 decades Mr. M focused his efforts on Civil Rights Law—eventually graduating with a law degree and challenging efforts by local law enforcement to profile African American citizens throughout Louisiana and eventually in Michigan. Mr. M explained that it was hard to understand the communists prior to WW2—they advocated for things that you had to experience the injustice of in order to find reason to support them. Though Mr. M had a relatively privileged childhood, the contrast between his experiences in World War II—fighting against ethnic and racial injustices globally—to the experiencing of Jim Crow first hand within days of his return proved sufficient to give meaning to the CPUSA’s message about racial equality.

Given the increased level of labor activity and interest in socialist politics across the country, how might your history of American communism matter in our current political moment?

I hope that my work is seen as a way to reevaluate our understanding of a few key subjects in American history. Much of what I write and talk about has been mentioned before, by authors such as Harvey Klehr or David Shannon or Theodore Draper. But the error I feel previous authors have made, which is not an all-encompassing criticism but it is very much a criticism of the Cold War and its impact on academia, was a proclivity to view communists as estranged outsiders from the start. The Communist movement itself was depicted as some sort of monolith—one that starts in Moscow and filters out almost perfectly into the various localized elements like a blanket submerged into water. In this metaphor, the water is communism and the blanket represents the various components that soak it up into a movement. The falsehood, however, is thinking that there is only one blanket….or that the blankets are all made out of one material—instead of recognizing that despite uniformity in certain areas of the Communist movement that was not the case across the board.

Ideally, one component people should take away from my work is the concept that communists were just like numerous other radical activists in American history—like the Germantown Quakers, like the minutemen, the Knights of Labor, and even the Socialist Party from which the American Communist movement was born. When we talk about abolitionist societies, for example, there is little need or desire to attach the localized movement with the global movement to abolish slavery. Sure, we could entertain such a discussion about the process of Great Britain, Germany, and other European nations taking steps to limit and end Transatlantic Slavery; but that doesn’t necessarily help us explain or better understand the experiences of slaves living in America nor does it necessarily provide us with a better foundation to understand the domestic abolitionist movement. Much like American Communism, there was a political world to the abolitionist movement—one which was also similarly abridged from its localized community element. Unlike the history of abolitionism and slavery, however, there is an almost knee-jerk tendency by Cold War-era historians to link up the domestic communist movement and its acute goals with the broader goals of international communism.

Another large component of my work seeks to challenge the idea that there existed little theoretical development in the realm of Civil Rights activism for people of color and women prior to the 1950s and 60s. Between the two World Wars, the Communists were some of the most passionate advocates of women’s rights both inside the realm of politics and in the workplace. While the AFL followed Samuel Gompers’ step of a hesitant effort of organizing women in the textile trades, the Communist Party and William Foster’s Trade Union Educational League placed women’s workplace rights at the front of its demands. The 1926 Passaic Strike, which involved a near split 50/50 male/female workforce, was organized by two TUEL activists and only LATER taken on by the AFL once the strike proved to capture national attention. Similarly, with regard to people of color, while the NAACP focused its efforts on building legal cases against national injustices, the Communist Party involved itself in a multitude of efforts to both promote an end to racism while also providing a platform for numerous educated and young Black intellectuals to speak up. The one I will never forget was Otto Huiswoud—one who I believe will go down in history as one of the earliest theorists to coin the concept of what we refer to today as “systemic racism”. Huiswoud’s argument with a Soviet pawn (John Pepper) in the Daily Worker serves to this day one of the best examples of both American resistance to Soviet oversight on the issue of racial theory, as well as one of the earliest moments of the suggestion that racism is upheld through societal norms—not simply by people “acting racist.”

Together, I feel that this reassessment of the American Communist movement can help future generations understand where the struggles we fight today have agency and placement in the more radical strands of thought. Once we get over that hurdle, perhaps we can begin to accept that the demands by Communists in the 1920s to end racial, sexual, and economic injustice were actually not that radical as we thought. In fact, many people today are likely to find that they agree with numerous programs promoted by the Communists throughout their heyday and decline.

Now that your book is published, what are some histories you are looking forward to reading?

I’m very much looking forward to reading through the historiography of Eric Foner, who I’ve been asked by International Publishers to write on. Foner’s work on the American labor movement and the TUEL were monumental for my research, but oddly they are not utilized heavily in contemporary labor classes on the more radical side of activism.

Outside of what I’m planning on working on personally, I plan on doing some reading and investigation into the Communist Party’s role in the 1960s—especially with the dawn of newer groups, such as Bob Avakian’s Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) and the Black Panthers. Much like the various Leftist groups of the 1920s and 1930s, I feel that the era of the 1960s has another chapter to tell of the radical Leftist experience. But part of me also wants to go further back in time, look more to the Knights of Labor and the precursor organizations that ultimately resulted in the rise of Communists by 1919. The goal would be to contribute to what numerous historians have increasingly defined as the “history of the Pan-Socialist Left in America.” Mark Bray was the first to mention this concept to me back in 2014, and I’ll never stop using that phrase. The idea of the Pan-Socialist Left is that much like the communist movement was plagued by factionalism and sectarianism, so too is the broader constituency of the Left. In fact, Communist Party in-fighting might be just the loudest example of a much more broad and common tendency among Leftist organizations in terms of divisions, factional camping, and the desire by certain elements to seek power within the movement at the cost of movement gains. The complexity of the Left, in short, needs explaining—and there’s a lot of reading and research that must be done in order to do that explaining.