Ever wonder if it’s safe to bring an artichoke to lunch when you’re trying to convince someone to speak up on the job? Want to know how a Tampax machine can help you make progress at the bargaining table? Did you hear what happened to the boss who ordered his secretary to sew up a hole in his pants while he was wearing them?

All of this is part of the story of the 9 to 5 movement of women office workers – a movement that began almost fifty years ago, when I was a clerk-typist at Harvard University and a group of us got to talking about what bothered us about our jobs. The Boston-wide organization we founded was called 9 to 5, named after the hours of the work day.

In 1973, the 20 million women office workers in the US. economy – people like me – were basically invisible. When people pictured a worker, they saw a man in a hard hat, brandishing a wrench. Yet here we were, and our ranks were growing. Millions of women were flooding into the workforce.

1973 was the great economic tipping point when families began to be worse off than the generation before. As a result of the civil rights movement and the women’s movement, workers had new expectations, new dreams.

We 9 to 5’ers sensed that we had our finger on the pulse of something big. We considered ourselves the heirs of the garment women at the turn of the 20th century, immigrants, teenagers, who went on strike by the tens of thousands and transformed the labor movement. Their slogan was Bread and Roses. Our slogan became Raises and Roses.

Some of us called ourselves feminists; others did not. But we all wanted equal treatment, and we had no lack of things that made our blood boil.

Women earned 57 cents to a man’s dollar. Some of us were doing the same work as men for less pay. Office work sounded like a step up from factory work. But to our surprise, it paid less than factory work – a lot less.

Back then, no used the term “glass ceiling” – meaning that women could only advance so high before they hit a sometimes invisible limit. But the phenomenon was real. Our jobs were dead-end.

The lack of basic respect was galling. One woman said, “We are referred to as girls until the day we retire without pension.” Many of us were expected to do favors – all kinds of favors – for our bosses.

Start-up

We handed out a newsletter and a survey all over town. When women responded, we’d call them up and invite them to lunch. As a full-time staffer for our organization, I’d sometimes go to two or three lunches a day (that’s where the catastrophe with the artichoke came in).

Listening carefully to how people described their problems, we discovered that a lot of our assumptions were turning out to be wrong. We thought women would be ready to form small groups and march in to their bosses’ office to demand better working conditions. They weren’t. We had to step back, meet people where they were, and figure out what they could do.

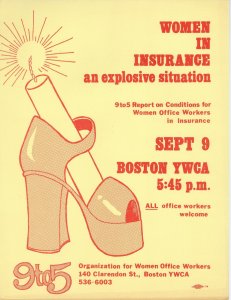

We ended up with a three-part strategy that combined constant media coverage, pressure from government enforcement agencies, and what you might call “whistle-blower” information – tips whispered to us by women workers about the nefarious deeds taking place inside the executive suites.

In multiple ways, we gave women the opportunity to act together to win improvements. And we claimed those wins and made them public, so that others could learn from those examples.

When we invited women to send in nominations to a Bad Boss Contest, entries poured in. Yes, there was the boss who needed his pants sewn up, and the one who fired his secretary for bringing him a sandwich on white bread instead of rye. There was the one who handed his secretary a warm container of urine to carry to a lab, and the one who asked his secretary to snip his nose hairs. After our 9 to 5 posses visited these “winners” at lunchtime with TV cameras rolling, bosses changed their ways.

All over the city, managers were shocked. Who had ever heard of office workers speaking up for their rights? It was as if the wallpaper had come alive.

Next, we trained our sights on the First National Bank of Boston, the biggest bank in town.

The bank’s own affirmative action report showed that women were underutilized in 15 of 36 job categories. The chairman of the bank earned as much in one day as a clerical worker earned in a month.

We launched our campaign against The First with a splashy press conference, declaring 1979 “the Year of the First.” We started an anonymous employee hotline, leafletted without pause, reached out to community leaders, held demonstrations at stockholder meetings.

By the end of “the Year of The First,” 51 women had been promoted to officer jobs. Training opportunities and vacation time were expanded. And the bank gave a company-wide raise of 12 percent, the largest increase in the bank’s history.

Going National

Our organization spread across the country, to New York, Cleveland, San Francisco, Baltimore, Milwaukee, Atlanta, Seattle – dozens of cities. 9 to 5 felt like home to a diverse range of women: those with a high school education and those with college degrees; white women and women of color; young and old. That diversity didn’t just happen; it took hard work and a conscious commitment. We kept the focus on our common target – the boss – and linked arms in pursuit of common goals.

All along, we recognized that if you want a say on the job, protection from being fired, and higher pay, what you really need is a union contract. So we set about exploring a union option for women who wanted that opportunity.

In 1975, the Service Employees International Union offered us our own charter and the right to hire our own organizers and run our own organizing drives. Our Boston union was called Local 925. By 1980, our District 925 was in full swing nationwide, operating alongside our non-union 9 to 5 wing. The two entities were sister organizations, distinct but entwined, both bringing women together for rights and respect.

Clerical employers – from banks to universities – were determined to remain non-union. We ran into ferocious opposition and wily union-busting consultants. In response, we developed a range of sometimes wacky tactics involving – well, cowbells, a one-day strike known as “the herd,” and not least…the Tampax machine.

What We Won

The 9 to 5 movement fell short of our goal of organizing 20 million office workers, yet we accomplished a great deal.

For every company that we targeted specifically, many more scrambled to clean up their act. For every individual who joined 9 to 5, many more watched and listened and were moved and changed. Countless bosses started getting their own coffee.

The actress Jane Fonda approached us to ask how she could help. The result was the 1980 hit comedy “9 to 5,” starring Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton, who composed her enduring anthem for the film. The movie was an enormous boost for our efforts to expand the national conversation on gender at work and change society’s expectations for working women.

A lot has changed since the 1970’s. Pregnancy discrimination and sexual harassment are illegal. The pay gap between men and women has narrowed – it was 57% in 1973, and now it’s 82%. There are more women in management and more women in union leadership.

But much remains to be done.

Being a working person today is in many ways tougher than it was 50 years ago. In the gig economy, it can take a patchwork of jobs to put food on the table. Workers are on call 24/7. Computerized monitoring is often brutal. Union jobs have declined. A smaller percentage of workers have break time or sick days or pension coverage. Students and families are burdened with debt. Millions of women lost their jobs in the pandemic. Race and sex discrimination are still widespread.

Even so, I’m hopeful. Support for unions among workers is way up, and we’re seeing a surge of new kinds of organizing to meet the challenges of the 21st Century. 9 to 5 is still active. SEIU Local 925 is still going strong.

As the song says, “Every generation’s got to win it again.”

For the answers to those questions up top – the ones about the artichoke, the Tampax machine, and the boss’s trousers – you’ll have to read the book.