Like me, are you bone weary of hearing non-stop news coverage of Donald Trump? Do you roll your eyes when the pundits “discover” the working class at election time, and then groan when you realize that by “working class” they really only mean white guys? Are you itching for an entirely different public conversation?

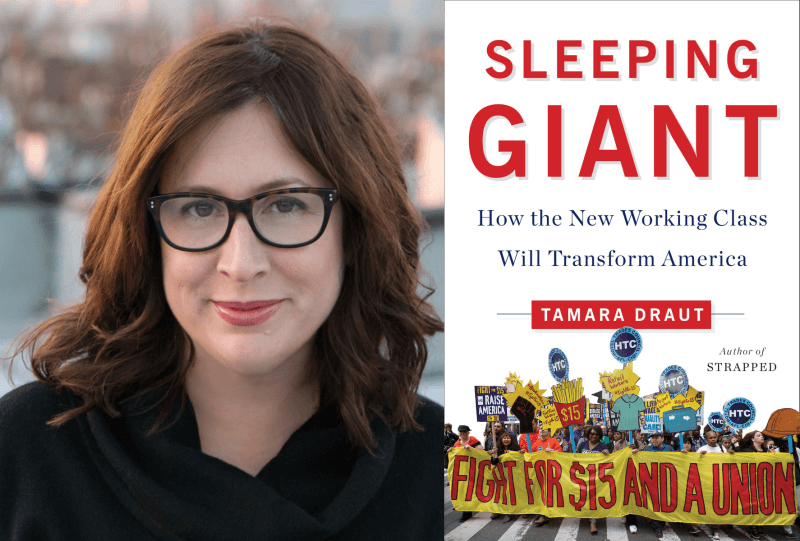

Tamara Draut’s Sleeping Giant: How the New Working Class Will Transform America (Doubleday, 2016) offers a sharp and widely-accessible discussion about the future of America’s working class, and so brings welcome relief in this election season. Her premise is that there is a “new” working class, compared to that of thirty years ago, that is more racially and ethnically diverse, more female and more likely to work in retail and service. Pointing to the Fight for $15 and the Black Lives Matter movement, for example, Draut posits that this “sleeping giant” may be in the beginning of effecting larger social and economic change.

In a swift and conversational style, Sleeping Giant distills much of the current research on inequality, bad jobs, and precarious work, and couples it with original interviews with workers and activists. We learn, for instance, that only five of the thirty fastest-growing U.S. occupations will require a bachelor’s degree; so much for the elite’s insistence that education will be the great leveler. The chapter on the “New Indignity of Work” could serve as an undergraduate primer for perils in today’s economy such as subcontracting, just in time scheduling, franchises and the “1099” independent contractor relationship.

Unlike many in the punditry class, Draut has read her history, and we see the work of Nelson Lichtenstein, Kim Phillips-Fein, and Judith Stein woven in here as she traces how America’s working people became so economically insecure. She tackles the legacy of racial and ethnic exclusion, and correctly finds great hope in the combination of the immigrant workers’ rights, fair wage and racial justice movements of today.

Yet in Draut’s insistence that today’s is a “new” working class with a new level of activism, she ultimately may do the “sleeping giant” a disservice. First, such a framing erases the extent to which people of color and women have long struggled and organized as part of the working class, as wage workers, enslaved people, and through their neighborhoods and families. In the long arc of history, mid-twentieth century steelworkers were anything but normative. Fight for $15 activists are part of a centuries-long struggle against capitalism, and they should benefit from owning that.

Second, Draut misses the major working-class activism of the 1970s. What we are seeing today is not a “new” working class, but a continued reconfiguration of the working class that started in the 1970s and grew from changes wrought by the 1964 Civil Rights Act. As these women of all backgrounds and men of color got new access to the full employment market in the 1970s, they made up a reshaped American working class that organized for more social and economic justice, including by pushing to form private sector unions. Draut covers how employers ramped up their resistance to unions in the 1970s, but somehow skips the decade’s worker’s movements that inspired the corporate resistance. When we re-write the 1970s struggles back into the story, it becomes more clear that today’s labor activists are part of a much longer movement by women and people of color to gain full access to the New Deal’s economic promise, a story that grows more even more rich with the inclusion of new immigrants since 1980.

Despite these omissions, this is a commendable and inspiring book that covers an enormous amount of material in a short space. Do yourself a favor this Labor Day: put down the Washington Post and pick up a copy of Draut’s Sleeping Giant.