Our series on new books in labor and working-class history continues. This month, Elizabeth Todd-Breland talks about A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago since the 1960s, which is being released today by the University of North Carolina Press. Todd-Breland, an assistant professor of history at the University of Illinois at Chicago, answered questions from Jacob Remes.

Lots of us watched the 2012 Chicago teachers’ strike with admiration and envy. What does looking at the history that preceded us tell us about it?

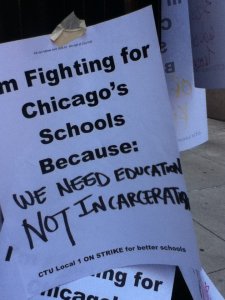

The 2012 striking teachers and their supporters were both protesting the anti-union privatization policies of the local Democratic administration and calling for resources to address the enduring structural inequities that relegated Black and Latinx students to separate and unequal schools and communities. In doing so, the 2012 CTU strike drew on a long history of Black education organizing in Chicago. During the Civil Rights and Black Power eras in Chicago, Black teachers engaged in dual struggles, advocating for themselves as Black public sector workers and on behalf of the predominantly Black students and communities that they served. Black teachers challenged school officials, and the CTU, and worked with parents and students in struggles for desegregation, community control, and funding equalization. These efforts contributed to dramatically increasing Black teachers’ representation in the teaching force, and the CTU, and increased teachers’ political power in the city between the late 1960s and 1990s. In more recent years, as corporate reform efforts and privatization policies challenged public education, the CTU returned to these tactics. The groundswell of community support that Chicago teachers received during the 2012 strike was a culmination of several years of organizing by community organizations and CTU members in Chicago’s Black and Latinx communities. Black teachers had long modeled these very organizing

practices.

In the time since the 2012 strike, other U.S. teachers unions have adopted this form of social movement unionism—connecting workplace concerns to community-based social justice struggles.

Probably the most famous teacher’s strike is the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville Strike, which is usually depicted as a moment of rupture on the left, between African Americans and the labor movement, and between Blacks and Jews. How does looking at Chicago, instead of New York, complicate the story of race, racism, and teachers’ unions?

Chicago was still in the very early stages of initiating a community control experimental district in the city’s Woodlawn neighborhood when New York teachers went on strike in 1968. Black educators and organizers in Chicago were very aware of what was going on in New York. Community groups in Chicago hosted convenings of educators and organizers involved in community control projects in New York, Washington, DC, Chicago and other cities. However, in Chicago, racist teacher certification practices were the major reason that Black teachers crossed picket lines in 1969. By the late 1960s, Black teachers made up a third of the teaching force in Chicago—a far higher proportion of teachers than in New York and many other cities. Still, Black educators in Chicago were disproportionately relegated to full-time basis substitute status, making them paid less, easier to fire than certified teachers, and barred from full voting rights in the union. Black educators in Chicago connected certification struggles to community control concerns and leveraged national media attention focused on Ocean Hill–Brownsville to advocate for their cause. In October 1968, as the conflict in New York raged and Black students in Chicago staged mass walkouts for community control of public schools, Chicago’s Black Teachers Caucus warned that “Chicago is going to make New York’s school problems look like a Sunday school picnic.” Groups of Black teachers had already organized wildcat strikes over the certification issue. By the spring of 1969 when the CTU went on strike over salary concerns, nearly half of Black teachers crossed picket lines. These teachers did not believe that the CTU represented their interests or the interests of Black communities. Black teachers in New York had crossed picket lines in 1968 in defense of Black self-determination in the Ocean Hill–Brownsville experimental school district. While the Black teachers who defied the 1969 strike in Chicago similarly argued for resources and control, the certification issue was their central grievance. This organizing by Black teachers, along with increasing pressures for faculty desegregation from the federal government, significantly increased the gross number and proportion of Black teachers, administrators, and Board of Education employees in the decades following the 1969 strike. As a result, Black teachers were also increasingly incorporated into the highest levels of CTU leadership—a phenomena not experienced to such a degree in New York City. Discussions of Ocean-Hill Brownsville often foreground Black-White conflict, but in my research I center intraracial politics in Black communities. This reveals a different set of political dynamics in considering racism in teachers unions and the ways that community control struggles vied for legitimacy in different parts of the country.

Contemporary Black politics seems dominated by neoliberal politicians like Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, Adrian Fenty, Deval Patrick, and, of course, Barack Obama. How does our view change when we look at figures like Karen Lewis?

In my work I reinforce the point that Black politics is not, and never has been, monolithic. In our current moment, there certainly is a strong group of Black liberals and technocrats that have exerted power at multiple levels of government. But, I would argue that that the grassroots organizing and progressive redistributive politics of groups and individuals who have more recently coalesced under the umbrella of the Movement for Black Lives has been as prominent a strain of Black political thought and organizing during the 21st century. In my work I trace continuities and ruptures in Black political thought and organizing from the 1960s to the present. Karen Lewis is a powerful conduit for this history. As a high school student, she organized Black student walkouts for community control in 1968. She marks this as an important phase of her political development. Later in her career as a high school teacher, she joined the CTU’s new Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators, with whom she attended reading groups, spoke out at Board of Education meetings, and worked to restrict charter school expansion. She recalled that working with this group “reminded me of my student activism days in the sixties, so I felt like I was right back to where I started from. It was just like this full circle thing.” She would go on to become president of the CTU and lead the 2012 strike that fought back against the politics of austerity in coalitions with community organizations. Her political trajectory underscores the permeability of different Black political ideologies and the importance of understanding Black political perspectives historically, intergenerationally, and relationally, rather than oppositionally and out of context.

Now that you’re done with your book, what books are you looking forward to reading?

Too many…in the best way! I’m currently reading Roger Biles’ biography of Harold Washington and Julilly Kohler-Hausmann’s Getting Tough, which I am teaching this semester. I’m also excited to read Barbara Ransby’s Making All Black Lives Matter and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s forthcoming Race for Profit. On the fiction side, I just ordered Rebecca Roanhorse’s Trail of Lightning and I’m reading James Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk in anticipation of Barry Jenkins’ film version of this beautiful book.