One of my first awakenings to the cultural divide between working-class and middle-class ways of seeing and being in the world was John Helmer’s 1974 book The Deadly Simple Mechanics of Society. Focused on a critique of American sociology, the book documented how routinely the educated middle class sees workers as “deadly simple” and, therefore, incapable of understanding the complexities of a modern society. But the deeper meaning of Helmer’s title was that educated middle-class professionals themselves had a “deadly simple” understanding of modern society, partly because they are generally blind to the complexities of working-class life and thought.

There are moments when we middle-class professionals, or at least the progressive part of us, recognize our blindness. Helmer was writing at one of those times, joined in 1972 by Sennett and Cobb’s Hidden Injuries of Class and in 1976 by Lillian Rubin’s Worlds of Pain: Life in the Working-Class Family, as well as by scores of New Left activists who took blue-collar jobs in those days in hopes of learning while doing their “march through the institutions.” We are again in one of those moments, I think (and hope), based on the Trump Shock we had two months ago. There is a humility in our oft-expressed concern about “living in a bubble” and in what I take to be a genuine curiosity about who “the white working class” really is and WTF are they thinking.

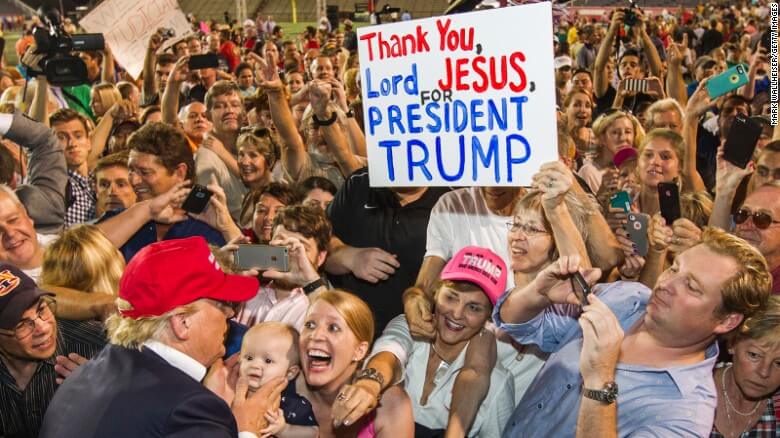

In the post-election discussion, some confident pundits, like Paul Waldman and Catherine Rampell, have written off white workers who voted for Trump as simply racists, misogynists, and other kinds of deplorables. Others, like Thomas Frank and Christian Parenti, see working-class whites as nearly blameless given corporate Democrats’ arrogant betrayal. But more often there is an altogether new quizzical sympathy for the white victims of deindustrialization, austerity economics, and deadlocked politics and an openness to learning who they are and why “they” have done this to “us” – that is, why they so overwhelmingly (67% to 28%) voted for an opportunistic billionaire carnival barker who may not be a fascist only because he so completely lacks integrity.

The beginning of wisdom in this exploratory attitude among journalists and scholars is that there is no single answer to that question. In order to move forward toward building a strong majority for economic, racial, and gender justice, we will need to find relatively simple generalizations that can guide action, but those generalizations need to be based on at least a rough-and-ready understanding of the daunting complexity from which useful conclusions can be drawn.

First, whites without bachelor’s degrees (the reigning definition of “white working class”) are a very large group – about 2/3 of all white adults (18 or older) or about 105 million people compared to 52 million whites with bachelor’s degrees and 82 million people of color both with and mostly without bachelor’s degrees. In this commonly used breakdown of the electorate, the white working class has been the largest and strongest group of Republican voters since 2000 (though, fortunately for Democrats, most of them do not vote). Two conclusions should be drawn from the sheer size and voting proclivity of this group: 1) They are too large a group to be ignored or written off. 2) They cannot possibly be all of one mind, with one uniform personality, one lifestyle, and with the very same experience, nor could they draw the very same conclusions from similar experiences.

Though you’d think those two points would be pretty obvious, it is precisely the grasping of these realities that I find new and heartening among the post-election commentary I’ve read. Both the fuck-them-they’re-all-racists and the they’re-all-decent-people-who-have-been-misled tropes are wonderfully out of fashion among professional commentators at the moment. In good measure this is based on a recognition that the working class as a whole has many different parts – politically severed by race, ethnicity, religion, and region – and that all of these parts themselves have parts that must be understood, including the especially large part that is white.

Law professor Joan Williams’s immediate post-election rant, “What So Many People Don’t Get About the U.S. Working Class,” for example, succinctly lays out some of the key cultural misunderstandings and misperceptions resident in the educated middle class, while also pointing to key differences between the “settled living” and “hard living” parts of the working class – a distinction of life conditions and cultural predispositions that crosses color lines, but that can play out in politically dangerous ways among whites. Williams concludes that “the biggest risk today . . . is continued class cluelessness” and a “class culture gap” that constricts middle-class progressives from maintaining a consistently strong focus on economic issues that can unify a large majority of working-class voters of all colors.

In a very different vein pollster Guy Molyneux’s “Mapping the White Working Class” divides white working-class voters into self-identified “conservatives,” “liberals” and “moderates” based on focus groups he conducted in Alabama, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. What he calls “moderates” is, I suspect, a mistaken moniker for a group who are simply not conventional conservatives or liberals but have a varying mix of views that do not align with these mainstream – and therefore, educated middle-class – political labels. But Molyneux thinks these “moderates” constitute about 35% of working-class whites and that they might support progressive Democrats with a strong economic justice message. Molyneux doesn’t pay explicit attention to class cultures, but he rings an important cultural bell in his concluding paragraphs:

Many working-class voters (and others) worry that public schools focus exclusively on preparing students for college, while neglecting the equally important task of preparing non-college-bound students for successful transitions into the workforce. . . . . A set of policies aimed at non-college youth would not just meet an important economic need for working-class families, it would also make an important moral statement that these young Americans matter and have contributions to make.

In addition to these insightful analytic frameworks, there has been a lot of very good reporting on white workers in specific Rust Belt locations. A lot of it is focused on 2008-2012 Obama voters who voted for Trump in 2016, but the best of it presents a wide range of voices with various views, many of which do not fit into tidy political categories. Of these, I’d recommend Alec MacGillis at ProPublica and The Atlantic and especially Van Jones’s Messy Truth episodes on CNN.

Jones’s interviewing style is particularly revealing, I think, as he does not hesitate to disagree and argue with Trump supporters as he presents himself as a progressive Democrat who has concluded he must live in a bubble because he cannot imagine why anybody would vote for Trump for anything approaching an honorable reason. Though predictably TV-edited for conflict and drama, this frank I-am-who-I-am style seems to win a steadily deepening respect from the people he’s talking with, while at the same time eliciting second- and third-order thoughts that reveal complicated, sometimes contradictory, thinking both within an individual and across the small group of individuals gathered for the purpose. There are no great revelations, but I found this exercise in how richly messy people are, including Jones himself, to be nearly therapeutic. Jones is black, which adds a special resonance and poignancy to his dialogues, but he’s also an elite middle-class professional who is vulnerably feeling his way outside his class bubble.

One important insight from this early round of Trump-shock commentary and reporting is that the white working class is a very large, diverse, and complicated group – one with people whose thinking is much more complicated than we educated folk tend to imagine. Some of them live in bubbles, too, and some of those bubbles are impenetrable. But just as many live a complicated rage that is open to conflicting and contradictory directions. Listening to and understanding that rage and arguing for a cogent progressive direction for it will take work of many different kinds. It will help a lot if we middle-class progressives begin with a heavy dose of humility and reflect on how our class position and experience, indeed our college educations, tend to make us unaware and dismissive of other ways of seeing and being in the world.