Original posted in Jacobin on September 2, 2014. Eric Hoffer was a conservative who only had the time to write because he was represented by a powerful leftist union.

Nicknamed the “longshoreman philosopher,” Eric Hoffer was the best-known working-class author and intellectual in postwar America.

From the 1950s to the 70s, the cold warrior’s essays regularly appeared in newspapers and magazines. President Eisenhower called Hoffer his favorite author. During the Free Speech Movement, the University of California, Berkeley appointed him an adjunct professor.

He was a frequent guest on network television, often praising conservative politicians like then-California Governor Ronald Reagan. In his first and most influential book, The True Believer, Hoffer criticized mass movements of all stripes, especially communism, and lauded the government’s containment policy.

Yet Hoffer was a walking contradiction. Despite his rightist politics, Hoffer belonged not just to the country’s most powerful leftist union, the International Longshoremen’s & Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), but its most militant local, the San Francisco Bay Area’s Local 10.

The central paradox of Hoffer’s life is even more striking because it was precisely the left-wing militancy of the ILWU that provided him the good fortune (yes, fortune) and time to write nearly a dozen books and hundreds of articles condemning radicalism, civil rights, and the social advances of the 1960s.

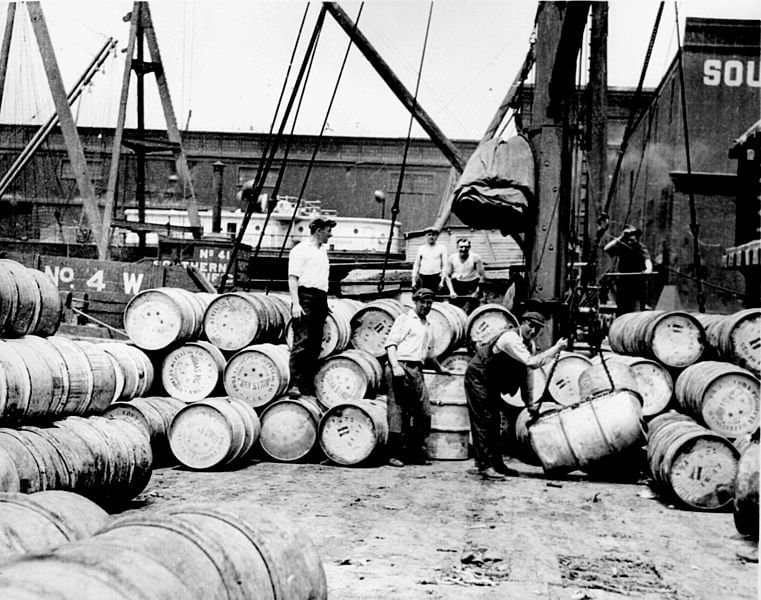

Hoffer worked as a longshoreman in San Francisco before and after becoming a successful author and public figure. During World War II, he had drifted up to the Bay Area from southern California, quickly finding work on the waterfront because the war effort had created a huge labor shortage.

Similar to the autoworkers, steelworkers, and packinghouse workers who formed militant, anti-racist, progressive unions in the 1930s, the ILWU was born out of the working-class anger, leftward turn, and rebelliousness that erupted during the Great Depression. Instrumental in securing the ILWU’s impressive gains were the cadre of communists and other leftists (including Wobblies and Trotskyists) who founded the union.

For longshore workers, the seminal event was The Big Strike, a 1934 work stoppage across the West Coast that exploded into a San Francisco-wide general strike after police repression left two dead on “Bloody Thursday” (henceforth, a legal holiday under the union’s contract). Ultimately, employers — under pressure from the Roosevelt administration — recognized the workers’ right to unionize, and the ILWU was born soon thereafter.

The ILWU wielded its power via repeated and countless “quickie” strikes during the late 1930s and 1940s. These actions forced employers to accept additional concessions related to work performance, including maximum weight on each sling of cargo. By the time Hoffer found his way to the Embarcadero, the ILWU had revolutionized labor relations in San Francisco, and members proudly embraced the nickname “the lords of the docks.”

West Coast longshoremen were “lords” because they earned high wages by blue-collar standards, were paid overtime starting with the seventh hour of a shift, and had protections against laboring under dangerous conditions. They even had the right to stop working at any time if “health and safety” were imperiled. Essentially, to the great consternation of employers, the union controlled much of the workplace.

The hiring hall was the day-to-day locus of union power. Controlled by each local’s elected leadership, the hall decided who would and wouldn’t work. Crucially, under the radically egalitarian policy of “low man out,” the first workers to be dispatched were those who had worked the least in that quarter of the year.

In the words of Herb Mills, a retired Local 10 member:

The hiring hall was indeed “the union.” It was the institution whereby the reality of community could be fashioned and maintained by men who had agreed to structure and divide their work on a fair and equal basis and who, through great strife and conflict, had won the right to do so.

In a real sense, sailors and dockers were the world’s first proletarians, toiling under corporate-controlled shipping lines in the first global industry. And like some of the pirates of yesteryear, the ILWU had created a system that spread the wealth among all its members.

In addition to this largesse, Hoffer also benefited from the tremendous flexibility ILWU members had won. In essence, rank and filers could decide when — and if — they wanted to work on a particular day. He also had the advantage of location: While there were no guarantees of a ship to work, San Francisco had long been the largest and busiest port on the coast.

All Hoffer had to do to maintain his union membership was report to the hall a certain number of days each quarter, attend monthly meetings, and pay his union dues. Thus, the “longshore philosopher” could work three days a week, write the other days, and know that he would get dispatched when he showed up at the hall. Or, he could work six straight days and take a week off to think and write, as he often did. And if that didn’t provide him enough latitude, union members like Hoffer could decide that they wanted to work in another ILWU-controlled port.

It was into this union that Hoffer stumbled, making (for a writer) an incredibly soft landing. He then proceeded to lambast the politics of the Left that had made his life so rich in money, safety, and workplace power.

Hoffer deeply appreciated the working conditions created by his powerful union, calling them “millennial” on numerous occasions. Yet he refused to praise the union and its leftist leadership, including President Harry Bridges. Bridges and the ILWU membership were highly critical of US foreign policy, especially its military interventions in Asia.

As a result of their politics, hundreds — perhaps thousands — of ILWU members were investigated for “communist sympathies.” Bridges himself was likely the single most persecuted labor leader during the McCarthy era — both by the government and a rightward-shifting CIO, which expelled the ILWU in 1950. However, he survived due to the tremendous loyalty of ILWU members, most of whom were not communists but almost all of whom loved what Harry and the other “’34 men” had done to create such a great job for working people.

Even in his private journals, some of which later were published, Hoffer rarely credited the union, and never Bridges. Though the man wrote constantly and voluminously, he rarely wrote about the union that made the selfsame writing possible.

He occasionally commented in his journals on the work he did — unloading transistor radios for eight hours at Pier 34 or working with a Portuguese partner while talking about his family. But the “longshoremen philosopher” never seemed to reflect deeply on the ILWU nor his role in it. For a while he became interested in automation and its impacts on workers, but largely was sanguine, hopeful, and arguably naïve about the benefits of capitalism for ordinary people.

The man lived a rich life of the mind — reading on the job during breaks, taking half-day walks to ponder particular intellectual conundrums, journaling fastidiously, and writing for publications. However, he never changed his views that politicians like Nixon and, especially, Reagan (first as governor, later as president) were noble and his union leaders dupes, “true believers” of false idols who demonstrated their own lack of self-confidence by joining a mass movement. Based on the limited record, Hoffer never spoke at meetings, never ran for any union office, and never volunteered in the union to help his fellow workers.

Ironically, the best-known working-class American of the Cold War era was a conservative who was lucky enough to find a job represented by the most powerful leftist union in postwar America. As such, his life represents the cognitive dissonance of many working Americans today: profiting from — albeit less so than in the past — the great gains of the labor movement yet unwilling to become union advocates.

As for Hoffer’s legacy, history can be cruel even to those who appreciate its fickleness. Today, few people know of Hoffer and fewer read him (though the term “true believer” still carries some rhetorical weight). The “longshoremen philosopher” was a powerful thinker, and the fact that he was a literary celebrity during the Cold War and consistently identified as “working class” is noteworthy.

While historians commonly associate the conservative ascendancy with Nixon and Reagan, they rarely note that the influential writings of the slightly older Hoffer predicted and praised the rise of the New Right. Scholars of Hoffer (generally conservatives themselves) inevitably note his working-class bonafides, but they don’t mention or analyze the irony of his membership in the leftist ILWU. In that way, they’re similar to all those, Hoffer included, who forgot that the labor movement brought us the weekend and much more.

LaborOnline is proud to feature this essay originally from Jacobin, a print quarterly that offers socialist perspectives on politics and economics. Support Jacobin and buy a four issue subscription for just $19.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.