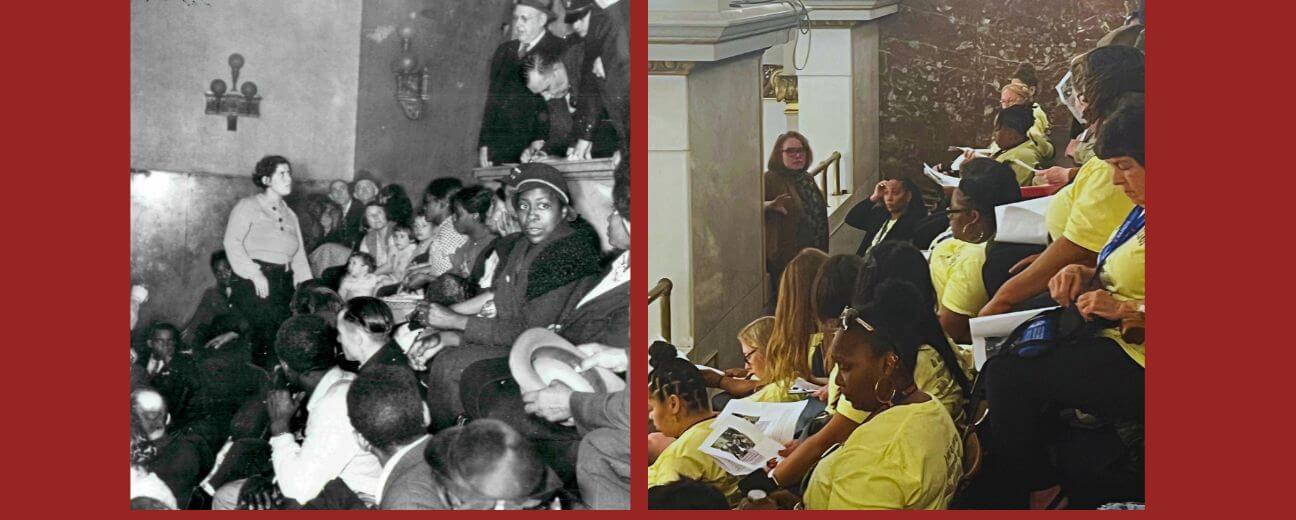

Every spring, over thirty women union activists are accepted to attend the Regina V. Polk Women’s Labor Leadership Conference, or The Polk School as it is fondly referred to. The Polk School is a program of the University of Illinois’ Labor Education Program in the School of Labor and Employment Relations and has been educating women union members to take on leadership roles in their unions since 1988.[1] This year attendees went on a labor history tour of St. Louis and the highlight was a reenactment of the April 1936 occupation of St. Louis City Hall by men, women and children who demanded that the city’s leaders increase relief appropriations chanting “til hell freezes over or we get relief.” At the time, the protesters camped out in the balcony overlooking the ornate city council chambers. The protesters were members of the American Workers Union who dedicated themselves to uniting employed and unemployed workers during the Great Depression.

This reenactment was particularly poignant given the recent protests across the country on college campuses as students build encampments demanding that their universities divest from companies that support the war in Gaza. When we arrived at city hall, we were met by a Washington University student whose professor Alderman President Megan Green was banned from the Washington University campus as a result of her participation in the campus protests against the war in Gaza. Alderman Green teaches domestic, social, and economic development in the School of Social Work at Washington University. Alderwomen Green was originally scheduled to host us at the city hall.

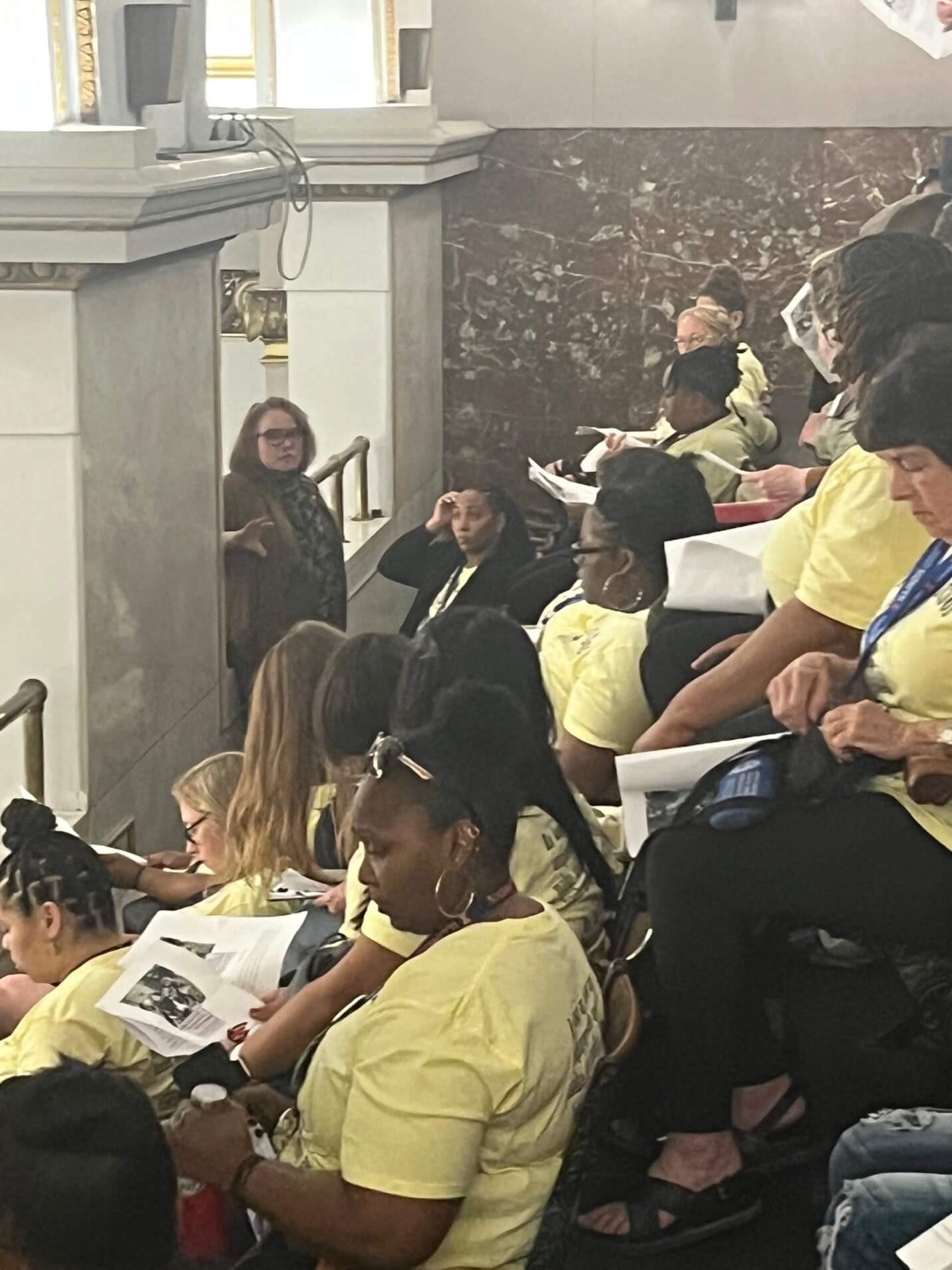

Led by labor historian Rosemary Feurer, the 34 Polk School participants filled the balcony of the chambers, just as their predecessors had done 88 years before. Shortly after they sat down, local labor activists acting out the parts of the police, Directory of Public Safety George W. Chadsey, a relief administrator, and local minister who were all working to remove the protesters from city hall confronted them. The Polk participants chanted, “We must have relief. If they want chaos, don’t blame us,” while others played protesters calling for relief. In addition to the chants, the participants broke out into songs such as “John Brown’s body lies a-mold’ring in the grave” and “Until we Get relief” to the melody of “We Shall Not Be Moved.” One Polk participant recited The Internationale as though she was performing in a poetry slam. And, when the skit ended, the women exited the balcony loudly singing “Solidarity Forever” as it echoed through the halls of the building.

Bringing history alive in the exact space that protesters demanded justice nearly 90 years earlier proved a powerful moment for these union leaders. And, it was made only more powerful, when we were introduced to Terry Kennedy, the Clerk of the St. Louis Board of Aldermen, who is the first African American to hold the position in the city. Clerk Kennedy, a former St. Louis alderman, told us about his family’s escape from the 1917 race riots in East St. Louis and their journey across the Mississippi River on a raft built by his grandmother. Clerk Kennedy has dedicated his life to racial justice as a student activist, journalist, and elected leader. It was a powerful end to an empowering day.

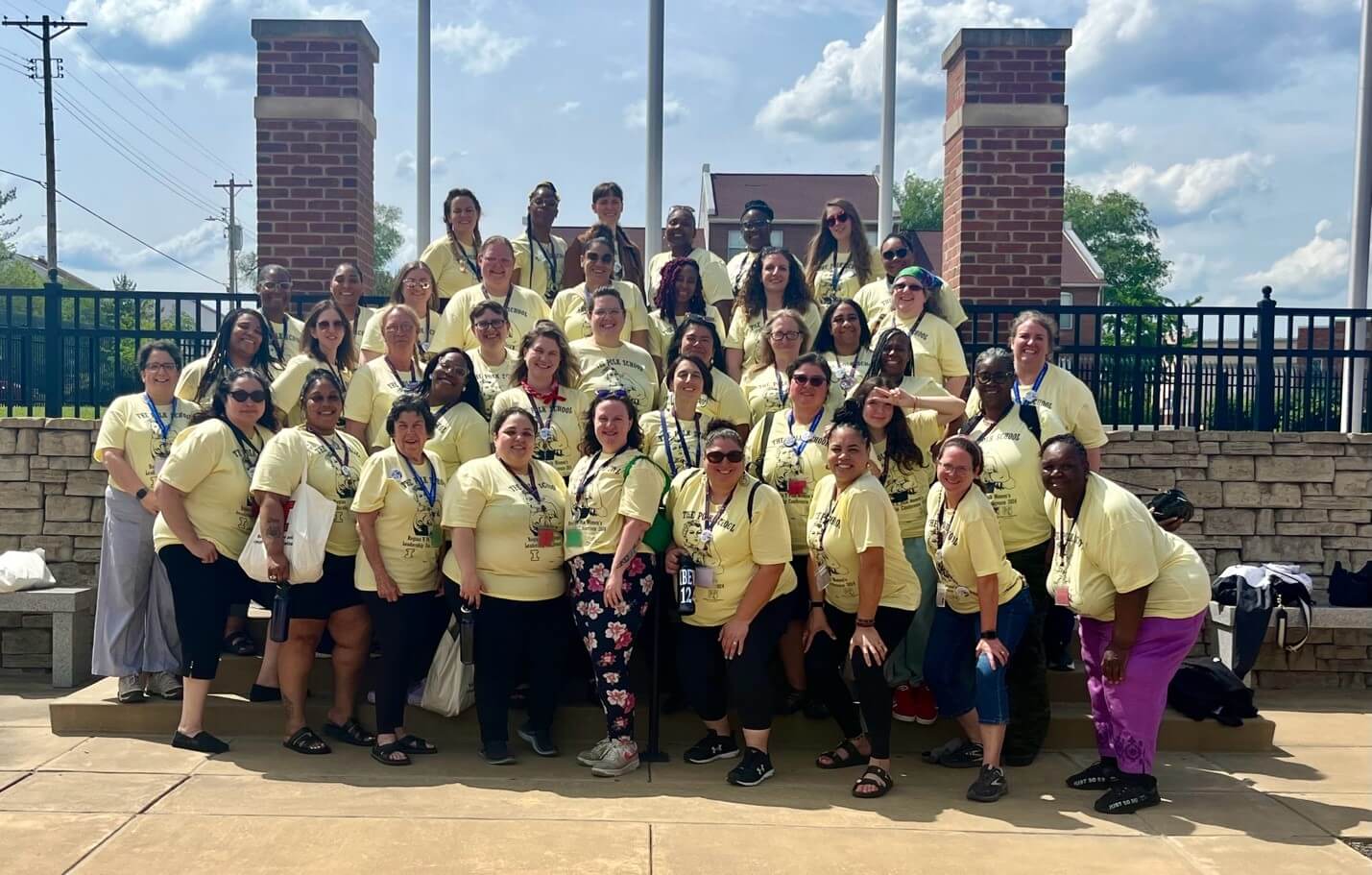

As the co-director of The Polk School, my role as a scholar-activist allows me to take my scholarship outside of the academy and to share it with workers around the state of Illinois and beyond. Programs like The Polk School represent the important connections between the community and the university that often go unseen and unspoken. Over the course of four days, women workers learn how to analyze the power dynamics in their communities and workplaces and to apply practical skills that will help them navigate organizational politics. They also learn from one another as each woman shares her personal stories and experiences in her union. This year’s 34 students spanned three decades of union membership, came from as far away as New Hampshire, and represented 15 different unions. The women work in prisons, universities, hotels, airports, post offices, on the tops of giant buildings, steel mills, call centers, and newspapers. Using popular education methods to teach history, economics, political science, and industrial relations, labor educators are able to break down the real and imagined barriers between the academy and the public. This month’s reenactment in St. Louis’ city hall is just one of many ways in which we can do this at the Labor Education Program at the University of Illinois.

[1] Emily E. LB. Twarog, “The Polk School: Intersections of Women’s Labor Leadership and the Public Sphere,” in Dennis Deslippe, Eric Fure-Slocum, and John W. Mckerley, eds., Civic Labors: Scholar Activism and Working Class Studies (University of Illinois Press, 2016).

Author

-

Associate Professor University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Labor and Employment Relations Affiliate Faculty, Gender in Global Perspectives Program and European Union Center, and Co-Director, Regina V. Polk Women's Labor Leadership Conference Author, Politics of the Pantry: Housewives, Food, and Consumer Protest in Twentieth Century America (Oxford University Press, 2017)