Below Toni Gilpin tells a pictured story of John Deere workers radical past, a story that connects to the recently launched John Deere strike. The Midwest holds a hidden memory of militancy and radicalism. And not just Chicago and the major cities.

Media coverage of the John Deere strike has included claims that workers make $60,000 and more per year. Jonah Furman’s reporting has disputed that figure, and he explains that long bouts of layoffs every year reduce workers’ pay. Moreover, he has brought into focus the fact that many pay for performance (incentive plans) –which are increasingly common– are subject to manipulation by management. These have long been the source of worker anger. Moreover, he noted that incentive pay plans pit departments and workers against each other in order to earn that pay. At Deere, “the top base pay for most workers is about $20. . . (though) in the fine print they said it’s an estimate based on ‘CIPP120%.’” CIPP stands fro Continuous Improvement Pay Plan, “a ‘team based incentive pay,” which pays the worker according to department productivity. Workers have quotas set by the company, and every 6 months, management increases the quota by 2%. If workers “hit 115% or more” of their quota, the company puts it into a reserve fund. Some workers realize a reward from CIPP but others don’t and they can’t really always figure out why. One worker told Furman that workers see it as wage theft. Certainly that’s how incentive systems in many factories in the 1920s and 1930s worked. Workers turned in tags and learned that there was some slide rule formula that created their total pay. It was utterly confounding and subject to the sense that theft was operational.

Toni Gilpin presented the following thread on twitter, one I thought was worthy of re-posting as a blog. It highlights the way that workers fought incentive plans in the past and how much they contributed to a militant fight for workplace justice. It connects the past to the present strike. –Rosemary Feurer, ed.

Jonah Furman has highlighted how incentive pay systems can only be overcome by a massive dose of solidarity, the kind that was systematically discouraged in the age of neoliberalism.

This ’49 contract was between Deere & the Farm Equipment Workers, not the UAW. Until the mid-1950s the FE was the dominant union in the Quad Cities, the center of the US ag-imp industry. The FE was a radical union, connected to the Communist Party, and I tell its story in The Long Deep Grudge. That book focuses on International Harvester, long the giant in the industry, but the FE was pivotal to organizing Deere as well.

Incentive pay is still the rule at Deere, as Jonah Furman recently tweeted about. These pay systems led to terrific shop floor discontent, because every worker’s pay rate was regularly renegotiated, as management re-timed jobs to eke out more production for the same, or less, dollars.

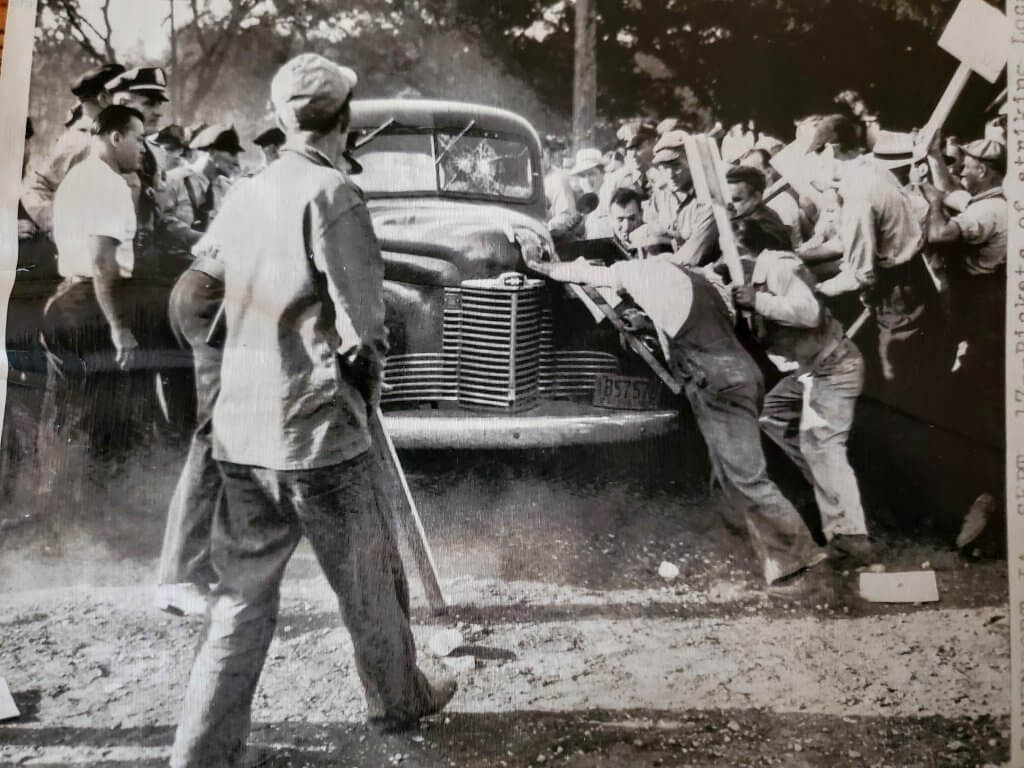

Quad Cities workers were once known for their exceptional militancy; this photo above indicates how FE members in E. Moline, Illinois (one of the Quad Cities) protected their picket lines. Part of this was because unlike auto, agricultural-implement companies like International Harvester and Deere used complicated piecework “incentive” systems, not straight hourly rates, for their production workforces.

Much of the Deere 1949 contract (pictured here) is devoted to stipulating workers’ rights in what was a purposely opaque system.

On the other hand the UAW’s Walter Reuther viewed increased production as a panacea that could benefit all parties, and so endorsed pay increases linking worker pay to higher production output. The Marxist, CP-influenced FE leadership saw these “incentive” schemes as a finely-tuned way of exploiting more surplus value out of the agricultural-implements workforce, and so the FE opposed productivity pay plans, and encouraged work stoppages when workers were getting short-changed or speeded up.The union committed to helping management meet its production goals, which meant no UAW support for walkouts or slowdowns protesting speedup. UAW contracts also had lower representation ratios, with much smaller steward bodies. UAW members enjoyed good wages & benefits but lost shop floor control. Speedup was routine and life on the job increasingly miserable.

FE contracts provided at least one steward in each department; those stewards could spend as much time as they wanted handling grievances on the company’s dollar. Walkout rates in FE plants were astronomical; 100s in each plant every year. Slowdowns were also a common FE tactic.

On the other hand the UAW’s Walter Reuther viewed increased production as a panacea that could benefit all parties, and so endorsed pay increases linking worker pay to higher production output. The union committed to helping management meet its production goals, which meant no UAW support for walkouts or slowdowns protesting speedup. UAW contracts also had lower representation ratios, with much smaller steward bodies. UAW members enjoyed good wages & benefits but lost shop floor control. Speedup was routine and life on the job increasingly miserable.

Even though they were both in the CIO, Reuther wanted to absorb all agricultural implement plants into the UAW and worked to get CIO consent to that. FE resisted. Beginning in 1947, anti-communist Reuther started to raid FE plants and by the late 1940s he declared war on the FE, and the Quad Cities became “the scene of the country’s largest union war.” FE members and UAW organizers literally slugged it out in the streets.

Despite the UAW’s greater resources, workers stayed loyal to the combative FE, but the hostile cold war climate took its toll, and in 1955 the FE merged with the UAW. (Deere Plow, though, went into the IAM instead.)

But for a long time ag-imp workers in the Quad Cities continued to bedevil both Deere and IH, actively resisting speedup.

This 1961 photo below isn’t very clear, but note the caption. This militant legacy is what Deere strikers can draw on. I don’t know how many Deere workers today are literal descendants of those FE members from back then, but seeing how they’re taking on both the company and the UAW leadership they are in spirit at least.