The public health and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated the problems with America’s two-tier system of college teaching.

Because most non-tenure track instructors make low wages, those fortunate enough to retain their jobs are unlikely to have the space or technology or support from home that they need to provide excellent instruction remotely. And because the majority of college instructors in the U.S. are temps, the threat of revenue shortfalls or declining enrollment has increased the precarity of hundreds of thousands of college teachers across the country, threatening both their livelihoods and their access to health insurance (if they have it through their work) in the midst of a global pandemic.

In some instances, most notably University of Michigan at Flint, schools have moved swiftly to layoff large numbers of their non-tenure track faculty. For PR reasons, administrators like to call these layoffs “non-renewal” of appointments, so they can frame the decision to fire lecturers as a cost-savings that supposedly prevent layoffs to salaried staff and faculty. In keeping with this approach, the University of Massachusetts at Boston Provost recently instructed Department Chairs to “Never slip and call this a layoff.” The implicit argument is that these were never jobs in the first place—just gigs—so anyone who made a career teaching without the protection of tenure has no reasonable basis to protest the end of their non-career.

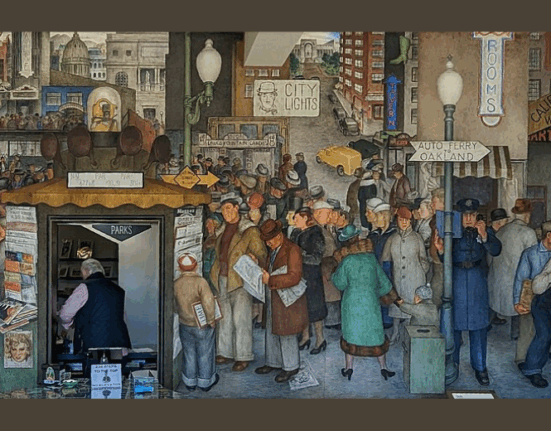

And yet, from City University of New York (CUNY) to Ohio University, people have been protesting. Mass layoffs have triggered a wave of spontaneous activism across the country against potential job losses. And increased faculty precarity has inspired more non-tenure track instructors to engage in community and union-based advocacy to resist the one-two punch of austerity and online education as “academe’s coronavirus shock doctrine.”

Non-tenure track faculty activism during the pandemic is part of a growing wave of resistance to the neoliberal university in the past decade. This resistance connects decades-old campus labor union campaigns for living wages and job security with more recent and intense demands for the decommodification of higher education in an age of seemingly endless austerity politics. At public colleges and universities, recent lecturer activism by labor unions is also part of a wave of post-Janus v AFSCME organizing. With public sector unions no longer able to collect fair share fees from non-members, unions have had to demonstrate their value to retain and increase membership. This has inspired a growing number of contract campaigns that go beyond bread and butter issues to promote the common good, and helped revitalize campus and statewide coalitions of campus labor unions.

At Rutgers University in New Jersey, whose President recently declared a fiscal state of emergency, faculty and staff unions have not only protested cuts to the most vulnerable workers, but have found common cause in proposing a work-share program to prevent layoffs.

At University of Massachusetts at Boston, where campus faculty were already in a protracted, fight for more funding from the UMass system and the state legislature, the notification that half of their non-tenure track instructors might not have jobs in the Fall has been met by protests and petitions.

In California, similar to UMass Boston and Rutgers, faculty activists are connecting their resistance to layoffs to proposals to improve higher education in ways that community allies can also rally behind. Leaders of the California Faculty Association at San Francisco State University got out front early with demands to reduce class size to retain faculty jobs and improve educational quality. UC-AFT has shifted its bargaining on behalf of 4,000 lecturers in the University of California system to focus on job security, and its open bargaining sessions on Zoom have allowed for rank-and-file members to create a raucous space in the software’s “chat” section that fuses public testimony with public protest against precarity and disposability.

Yet despite the more publicized protests against layoffs, and the looming threat of much worse on the horizon, as of early July, 2020, while many if not most schools have announced hiring freezes of new faculty and staff, mass firings of teachers have not been as swift as some feared. This is because lecturers are also essential to the success of their schools. “Just in time professors”, who don’t usually receive formal employment contracts until after they’ve started teaching, so that they don’t have to be paid if their courses don’t have sufficient enrollment, are not just disposable. They are also indispensable to meeting increased or unanticipated teaching demand. Just as declines in international student enrollment at U.S. schools are likely, so are increases in students wanting to attend public colleges or universities in their home states in order to reduce the cost of tuition for “remote” education that is perceived to be inferior to in-person instruction. And it’s difficult to determine how much CARES Act funding, or additional Congressional action, might be able to mitigate the downturn for higher education.

As college administrators assess the changing landscape, most lecturers are expected to live with an even greater level of uncertainty than usual about whether and how much they’ll be teaching this Fall. Whatever happens, their function is to absorb the costs of schools’ adjustments to the new reality so that others—particularly tenure track instructors and administrators— can weather the storm more or less unscathed.

Lecturer activism is therefore challenging not just their own contingency, but the whole system of “academic capitalism.” At its root, this is a system that, a 2016 TIAA report demonstrated, channels the profits gained from hiring cheap and precarious faculty labor into bureaucratic, non-instructional empire building. At a moment when students are complaining about educational quality of online instruction, it’s well past time for schools to reinvest in teachers and teaching.

Trevor Griffey, PhD is Lecturer, Labor Studies at UCLA, U.S. History at UC Irvine and Vice-President, UC-AFT Local 2226 at UC Irvine