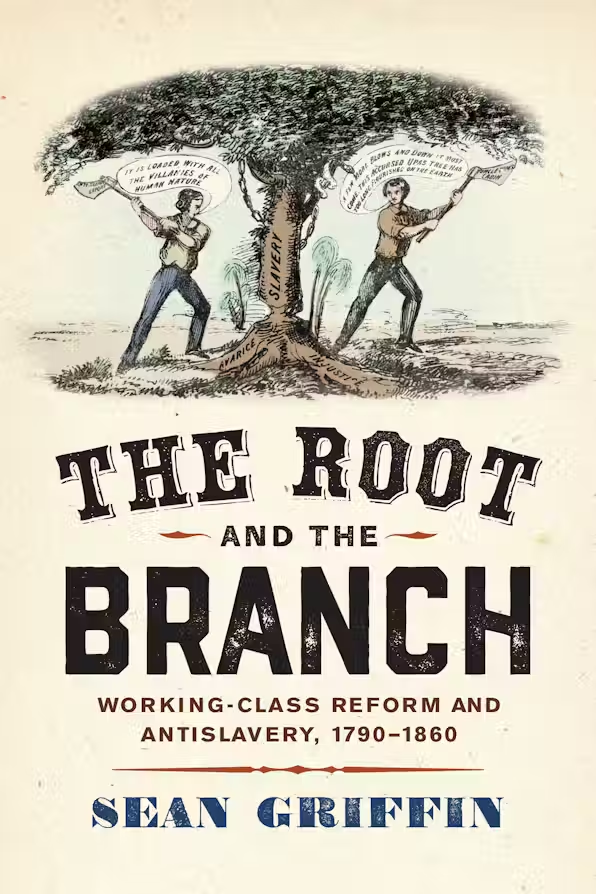

The Root and the Branch: Working Class Reform and Antislavery, 1790-1860 conveys the robust influence of labor reform and antislavery ideas and movements on each other from the early National period to the Civil War. Griffin argues the movements affected each other more than is usually realized, and that workers, and radical ideas about the labor question. Griffin also sought to answer the call issued long ago by Eric Foner’s, Free Labor, Free Soil, Free Men, to fill out the way that various groups understood the term free labor. Griffin agreed to answer a few questions about the book’s contributions.

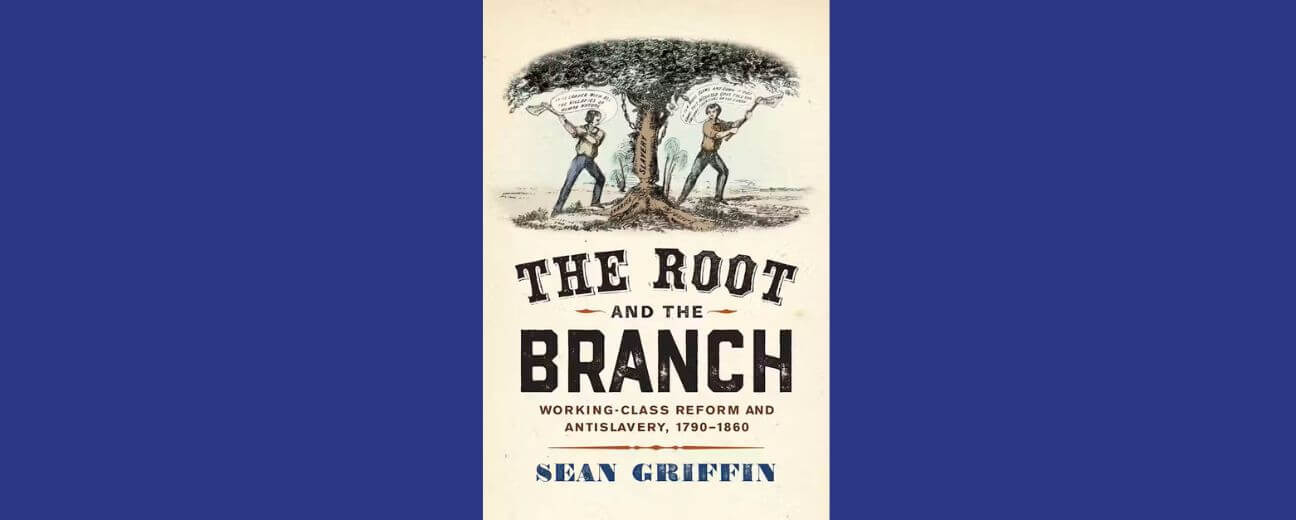

Tell us about the image on your book’s cover, and how it conveys some of what you are trying to do in this work?

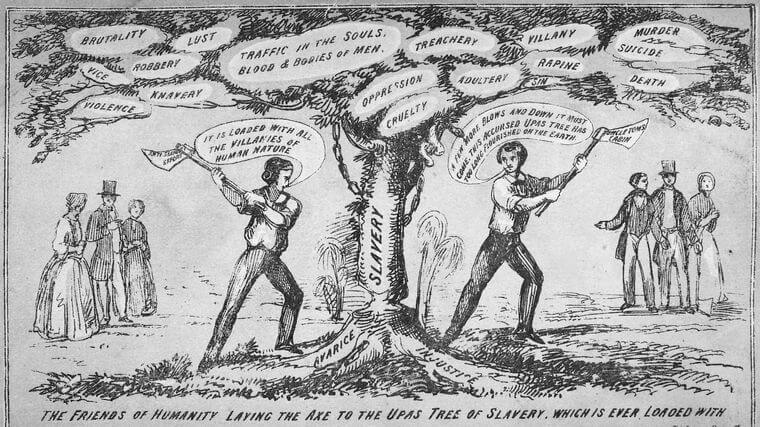

The print around which the cover art is based comes from a collection of antislavery literature published in Britain in the 1850s. I first saw it thanks to Madeline Lafuse, a fellow graduate student at City University of New York. Maddy presented a paper about how the upas tree, a supposedly poisonous species found in tropical climates, was used by antislavery activists as a metaphor for slavery. But I thought that the image and the tree metaphor also resonated with my book on several levels. Not only are the “friends of humanity” chopping down the tree depicted as sturdy workingmen, with their artisan blouses, but I found that the tree metaphor was also used by labor activists in the period to argue that slavery was but one branch of the “root” problem, i.e. the oppression of labor more generally. However, there were some labor abolitionists, who reversed that metaphor, arguing that chattel slavery had to be abolished first before wage workers could hope to see any progress. So I was trying to capture some of these contradictions and ambiguities in the title of my book, and I thought the print was a good visual representation of that.

down the tree of slavery. The semimythical, poisonous upas tree was often used as a particularly

insidious illustration of the pernicious effects of slavery. Credit: New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

The land issue becomes inescapably intertwined with the slavery issue as the territorial expansion of slavery becomes a major political issue in the 1840s and ’50s, so that even labor reformers who weren’t necessarily disposed toward abolitionism are forced to confront it—with the result that many end up becoming part of a broad antislavery political coalition.

Telling the story of the working class in this era, uniting a story that connects both North and South, enslaved and free, seems nearly impossible. You seem to have found an arc to tell that by starting with Paine’s Agrarian Justice. Can you tell us how that is an important starting point?

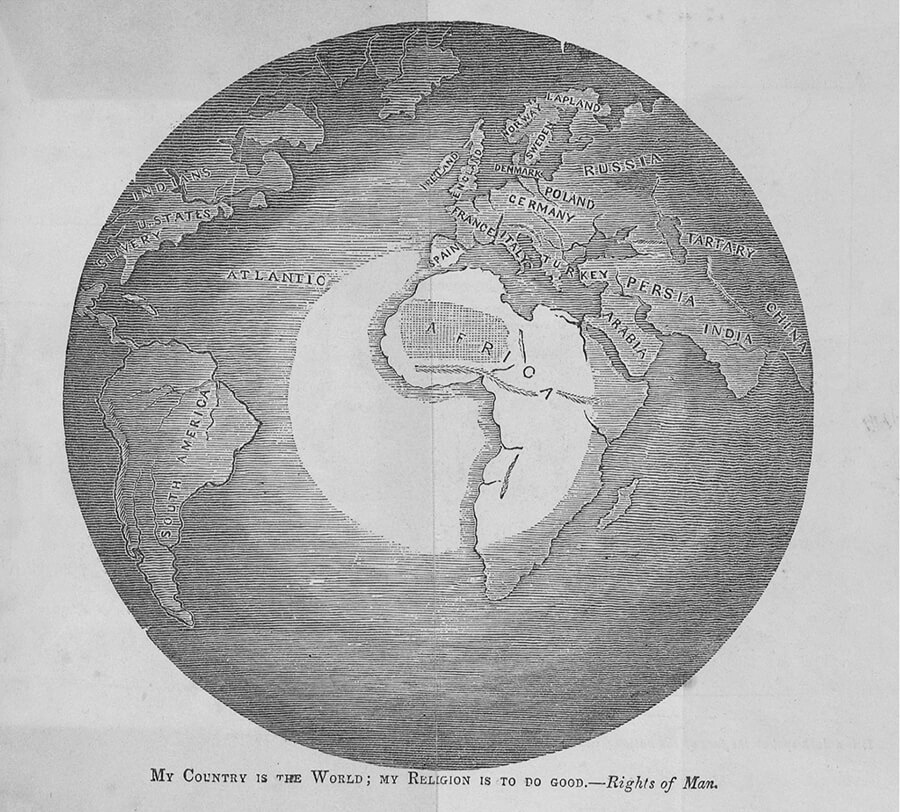

Well, I found that a common theme linking early labor movement organizations and activists together—in fact, arguably the most important theme, alongside demands for education, a living wage, and a ten-hour workday—was the demand for access to land. I don’t argue that Agrarian Justice necessarily had a tremendous influence on labor reformers, although they remember and revere Paine. But the demand for land, or “agrarian” reform as a form of economic justice is a constant throughout this period, from the Spenceans in late 18th century England to proposals of the first General Trades Union in Philadelphia to the National Reformers of the 1840s, who ultimately influenced the passage of the Homestead Act in 1862. The land issue becomes inescapably intertwined with the slavery issue as the territorial expansion of slavery becomes a major political issue in the 1840s and ’50s, so that even labor reformers who weren’t necessarily disposed toward abolitionism are forced to confront it—with the result that many end up becoming part of a broad antislavery political coalition.

quote from Rights of Man with an image of an illuminated Africa at the center of the globe. Credit: Yale Beinecke Library. From Griffin, Root and Branch, 27

The early labor movement adopted terms like wage slavery and white slavery, and scholars have concluded an identity in whiteness and victim narrative was a bar to an expansive politics based on solidarity, that this set white workers up to think of themselves as having little in common with enslaved or free people of color. You come up with a somewhat different conclusions. Can you tell us a little about your perspective?

I pay close attention to the “wage slavery” debates in the book, and I agree with the whiteness scholarship that ideas about race and slavery certainly shaped white workers’ identities in the period, and could also act as a barrier to solidarity. But although I take the ideas seriously, I also wanted to move beyond an analysis of the language of wage slavery. Not only has that topic been covered so well already, but the very ubiquity of the language of wage and white slavery in the period hints at its limitations as an explanatory factor. Ultimately, I think it comes down to who was using the term, and to what end? If figures as different as George Henry Evans, William Goodell, and John Henry Hammond were all using it, then that suggests to me that you have to scrutinize the context and intentions that shaped its use. Was the language being used to diminish the sufferings of enslaved people and the injustices of chattel slavery, or was it being used to call attention to the plight of free workers by using the most obvious metaphor for oppression that was available?

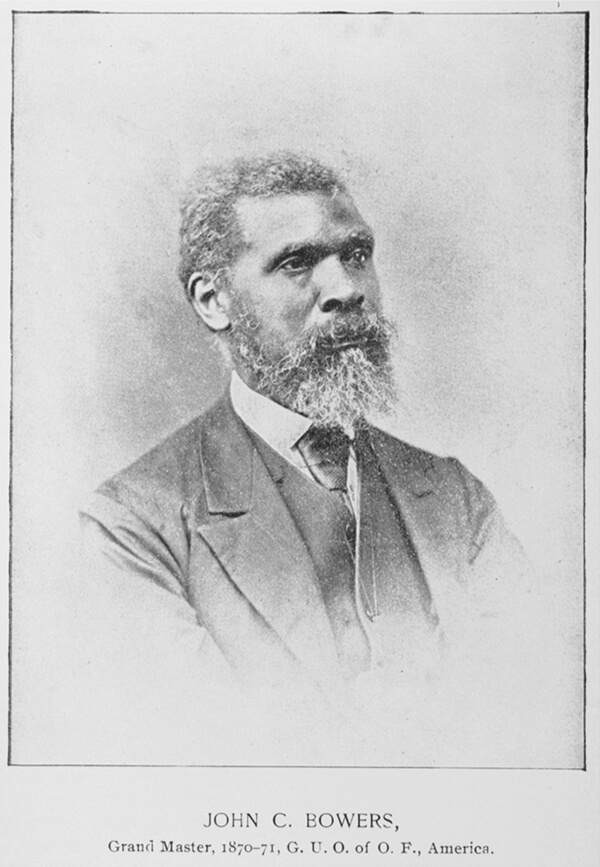

Evans, for example, stubbornly clung to white slavery metaphors throughout his career as a land and labor reform activist. But he solicits the participation of abolitionists, allies himself with Gerrit Smith and the Liberty Party, and demands that John Bowers, an African American delegate, be seated at the National Industrial Congress. He may have prioritized the abolition of what he called “land monopoly” over the abolition of slavery—neither of which he lived to see—but those moments of solidarity are significant, I think, precisely because they were so exceptional in pre-Civil War America, outside the Garrisonian abolitionists.

Similarly, much scholarship now places land questions as an aspect of settler colonialism. You focus on the radical potential of the land question in the labor movement and its relationship to antislavery movements. You write that land reform became the “instrument by which the alliance between labor and antislavery, decades in the making, was finally if imperfectly cemented.”(155) Help us see what we would find in your book about this issue.

As I alluded above, I think that the land issue was instrumental in persuading many labor leaders and working people in the North that the expansion of slavery went against their interests, which led many to support the Liberty, Free Soil, and Republican parties, although that was by no means universal. But many veteran labor leaders, like William Heighton and John Commerford, who had been staunch Democrats in the 1820s and ’30s, become conspicuous in their support of the Republicans by the mid-1850s, by which time George Henry Evans was denouncing the Democrats as “the little Tory Party of holdbacks.” But it goes beyond Free Soilism—the working-class variant of land reform was a genuinely radical movement, one with its origins in the agrarian and leveller movements of the English Civil War and French Revolution. The working-class land reformers of the 1840s and ’50s went far beyond the Free Soilers or Republicans in that they questioned, not only the inequalities of land ownership and the wealth it entailed, but the very institution of land as a form of property. In that sense, they had something in common with abolitionists, who famously denied that enslavers could claim people as property in human beings.

Evans, for one, thought the Free Soil Party represented a “sham” version of free soilism, and tried to steer his organization into an alliance with the Liberty League, a splinter faction led by abolitionist Gerrit Smith. Smith becomes an enthusiastic adopter of land reform in the late 1840s, and collaborates with Evans on his land grant program for free Black New Yorkers.

Where most land and labor reformers fell short, of course, was in their failure to prioritize the abolition of slavery ahead of so-called “wage slavery” (or the “slavery” of land monopoly), as well as in their failure to fully consider the consequences of their demands for the indigenous people. Evans and others, like Thomas Skidmore and some of the Fourierists, try address this issue by arguing that Native Americans would also be eligible for free homesteads, and suggest that both Indians and African Americans could organize themselves into self-sustaining communities on the Public Lands. But of course, this ignores the fact that Native people were already on those lands.

You acknowledge the evidence for a fragmented working class that did not speak with one voice. But you insist that there is a way to trace the political and organizational developments that led Northern workers to be leaders in signing antislavery petitions, forming organizations and parties that opposed slavery’s extension, opposing racist pogroms, and joining the Union Army in disproportionate numbers. Can you highlight a few findings that show the importance of tracing this?

My findings here largely build on the work of previous scholarship. Voting records that correlate with occupational statistics are notoriously difficult to recover in this period, but Edward Magdol has shown that workers disproportionately signed antislavery petitions and joined abolitionist societies in New England, while John Jentz did something similar for New York City. Both studies deserve to be better recognized. Similarly, Evans’ opposition to anti-abolitionist riots and support for the Nat Turner Rebellion has been written about elsewhere; but less well-known are the ways in which he and William Leggett helped pioneer what later became known as antislavery constitutionalism. Mark Lause and Matthew Stanley have done great work on the working-class composition of the Union military… The book’s most original findings have to do, I think, with the ways that labor reform organizations and activists became part of a broader antislavery coalition in the North. For example, the National Industrial Congress was reaching out to the Liberty League and passing resolutions denouncing the Fugitive Slave and Kansas-Nebraska Acts. The book also makes a contribution in that it recovers the participation of African Americans in these movements—not only did the Industrial Congress feature Black delegates, but a number of prominent Black abolitionists, like Henry Garnet and Willis Hodges, not to mention Frederick Douglass, also endorsed the land reform movement, and they voiced support for Black-led labor organization and land reform as well.

The book’s most original findings have to do, I think, with the ways that labor reform organizations and activists became part of a broader antislavery coalition in the North.

You discuss the influence of Fourierists and Associationists, which is a movement not well known. Who were they and what role did they play in the story you tell?

I think the Fourierists, who referred to themselves as Associationists, are underrated in terms of their influence, even if their movement was somewhat ephemeral. The Associationists were the American followers of Charles Fourier, a French social thinker who posited that society could be brought into harmony if everyone lived in intentional communities known as “phalanxes,” and worked according to the principle of “attraction,” i.e. the work that each individual was naturally inclined towards. Even though some of his ideas were quite fantastical, they held a broad appeal for both middle class activists, like Horace Greeley, who were seeking to achieve “the harmony between labor and capital,” and ordinary workers who were looking for an alternative to the competition and exploitation of wage labor.

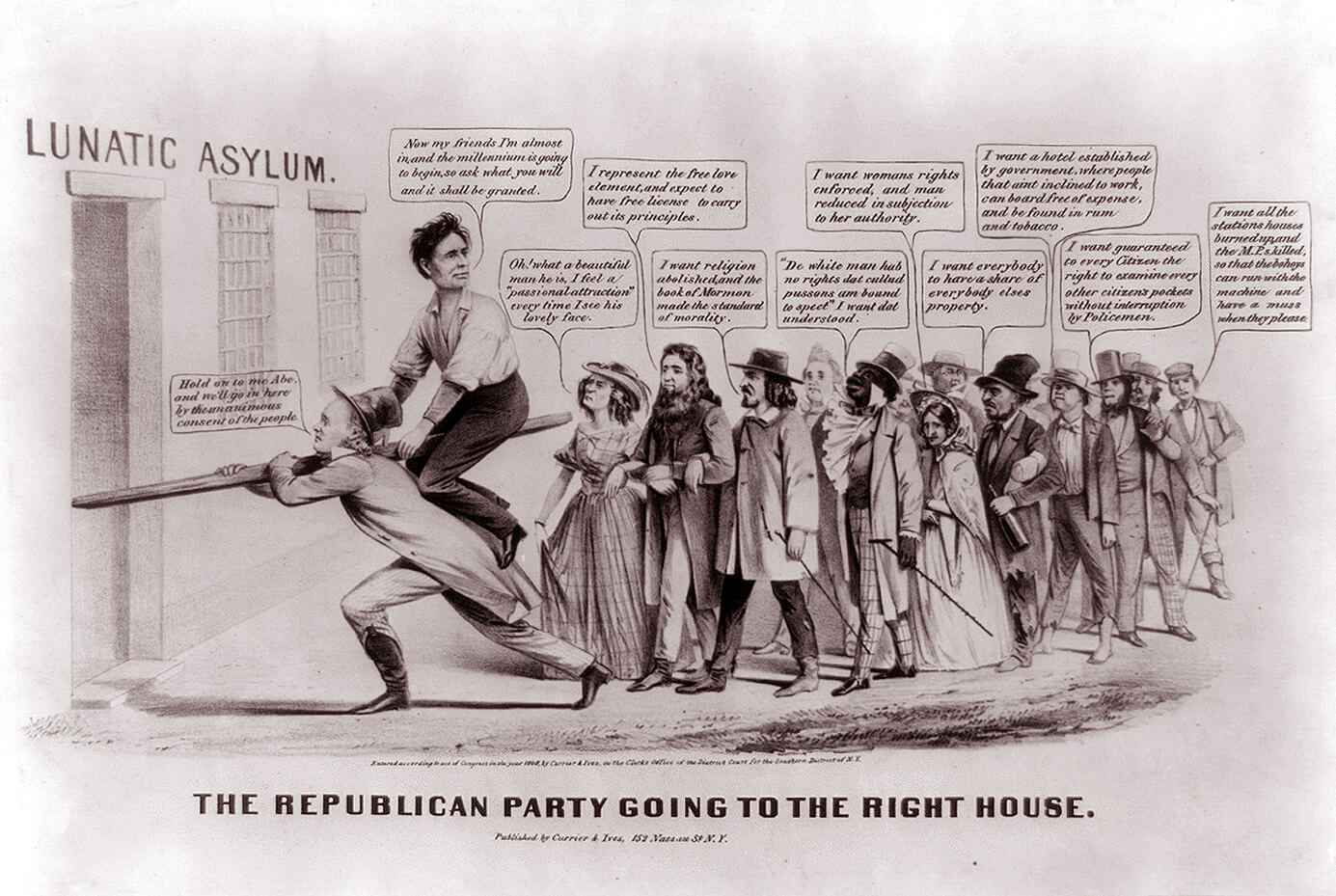

[Former Fourierists] inject a strain of radicalism into the early Republican Party, so much so that detractors try to brand the party as tainted by Fourierism and other forms of radical social experimentation.

To a greater degree than the other major ideological tendencies within the early labor movement, Associationists both paid a lot of attention to chattel slavery, and they overlapped much more in terms of their membership and involvement in abolitionist societies. This may be because they were more middle-class in their values and orientation, but the literature shows they attracted a lot of support from workers, especially in New England. The editors of Voice of Industry and leadership of the New England Workingmen’s Association were both Fourierist and strongly antislavery in the late 1840s. From the other side, abolitionists like John A. Collins, Elizur Wright, William H. Channing, and even Frederick Douglass were drawn to Fourierism. And then after it dies out, several figures who had been Associationists in the 1840s, like Greeley, Parke Godwin, and Charles A. Dana, reemerge in the early Republican Party. Although they had abandoned Fourierism by then, figures like these inject a strain of radicalism into the early Republican Party, so much so that detractors try to brand the party as tainted by Fourierism and other forms of radical social experimentation.

Sean Griffin is a historian of nineteenth-century American political, social, and labor history. His first book, The Root and the Branch: Working-Class Reform and Antislavery, 1790–1860, was recently published by Penn Press. Sean received his Ph.D. from the CUNY Graduate Center, and has received numerous fellowships and awards. He currently teaches at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York.