David M. Emmons’ provocative new book History’s Erratics: Irish Catholic Dissidents and the Transformation of American Capitalism, 1870-1930 deploys a wealth of theory and decades of research to reframe our understanding of the Irish Catholic working class. The term erratics, as he explains in his book, is a metaphor derived from glacial erratics, to convey the dissidence that arose among Catholic Irish workers who rejected American capitalism. J. Hollis Harris interviewed him about some of the book’s themes and arguments.

You use the term “IrishCatholic” as an important analytical device throughout History’s Erratics. Can you elaborate on the process by which you arrived at the term? Why do you as a labor historian insist on this rather than Irish Catholics, Irish Americans, or Irish immigrants?

I use the neologism “IrishCatholic” as a shorthand way of saying that many in Protestant America made no distinction between Irishness and the religion of most of the Irish immigration. I should add that Irish Catholics frequently made no distinction either. For them, being Catholic meant being not British and not Anglo-American. What for Protestants was the Irish curse was for my erratic Irish the ultimate Irish blessing. One Irish writer, Luke Gibbons, said that Catholicism was the Irish’s “ineradicable ethnic component.” Another one, Fintan O’Toole, wrote that “Irish Catholic had come to stand for some third thing born out of the fusion of the other two.” I decided to make the fusion literal by minting a new word.

I acknowledge that not all of those who came to America from Ireland were Catholics. But I also note, with emphasis, that the Protestant Irish immigrants called themselves what they were, “Scotch-Irish,” that is dissenting Protestants from Scotland removed to an Ireland they did not like and to which few pledged any allegiance. They were not erratics, out of time and out of place in America. I’ll never forget the young Protestant woman visiting Montana from Belfast who when introduced by her American hosts as “our Irish visitor,” politely but as firmly as the situation demanded, corrected her hosts: “But I’m not Irish, you know. I’m British.” She was not just professing her citizenship; she was claiming her shared culture. For purposes of convenience though not of total accuracy, I’ll let her speak for the whole of the Protestants of Ireland. Or, if that won’t do, let the host of scholars I assembled and cited in the book who said essentially the same thing, speak for the whole of them. Included prominently among those scholars is E.P. Thompson.

Throughout the book, cultural persistence between Ireland and Irish America seems to be a central, if not recurring feature of your analysis. The importance of political and cultural holdovers from Irish society like shoneenism, Catholicism, communalism, and others comes to mind. To your point, however, Protestant-made America was in the process of becoming both modern and industrial in the postbellum era. If immigration history and labor history are one and the same, as many historians contend, then how does your interpretation of cultural persistence help readers better understand the formation of working-class identities?

I never made an exact–or even inexact–reckoning of what percentage of the book was about Ireland and what percentage about America. I am, however, fairly certain that, with the obvious and important exception of Kerby Miller’s Emigrants and Exiles, I give the “home county” more attention than most historians of American immigration.

To the specific points of your questions: I picked the year 1870 to begin because I wanted to push my story deeper into the industrializing era of modern America. I also wanted to dodge some of the issues posed by the existence of American slavery as it influenced and confounded American labor history. The Irish Catholics in the work force of this modern and industrializing/industrial America were “pre-modern” and “pre-industrial.” That was true of a great percentage of all the immigrant/ethnic components of the American working class. This much is known and frequently commented upon. Herbert Gutman and many after him have made certain of that. Many in the American industrial working class did in fact come from “backward,” that is, pre-modern societies; meaning that many of the men and women in it were out of time and out of place and had to be “socialized.”

The “backwardness” of the Irish Catholics among America’s “pre-modern” labor force, however, is almost always attributed by historians to co-incidents, simple chronology, historical sequence, or a stunted historical evolution. For various reasons, usually left unexplored, they hadn’t “caught up” with modernity yet, but the unstated assumption was always that–kicking and screaming, to be sure–they would. That’s an advance over the days when modern Protestant America said that IrishCatholic backwardness was owing to racial defects–including the ones that made and kept them Catholics–and hence irremediable,

Both explanations, the “coincidental/chronological” and the racial, leave the story incomplete. Being pre-modern and/or pre-industrial are social conditions. They imply that Irish Catholics were backward because they came from a backward place–whatever the reason for that backwardness–and professed a backward religion. I don’t deny the superficial truth of that; I deny only that it explains much if anything of importance. The laggard habits of Irish Catholics were historically derived, but calling them only “pre-modern” or, as E.P. Thompson did, “semi-feudal,” implies that they were transient. Irish Catholic workers would not be forever out of time and out of place in industrial and capitalist America. Sooner or later, they’d catch up and get used to the place. I would add here that, sooner or later, they did. But not by 1930 when I close my account of their erratic years. I left what happened after 1930 to other historians.

My emphasis is on cultural values that go much further back in time than the pre-modern Irish Catholic immigration and direct involvement in working for wages in a modern American capitalist economy. Premodern was not just descriptive; it was evaluative. It meant “civilized.” Premodern was a term of reproach. That’s a conceit–with or without any racist origins; I substituted “traditional” for premodern. Traditional is morally neutral. It defines what a people are, not what they are not. Traditionalism is a cultural trait; it defines an active state of being. It is not about people in the process of becoming; it is about people as they were and preferred to remain.

This is an important point in my answer to the next part of your question. Irish Catholic involvement in the American labor movement is also frequently commented upon. Here also, however, the reason is almost always because so many of them were in the American industrial working-class–and spoke a kind of English. Circumstance, what I earlier called co-incidence, explains it. I’m of a different mind. I think they were “laborites;” more specifically, that they were industrial unionists and social democrats not from historical circumstance, but for reasons that antedate their knowing what “industry” and “working class” even meant, reasons that go back much further in their history than their entry through American factory gates.

The cultural values they brought from Ireland to America and passed down generation to generation were communal; I call them ecclesial; clannish will work, too. By whatever name, the idea of industrial unionism was a “birthright;” they were born to it. So was the idea that democracy had to be more than political. It had to have a social as well as a political component. In 1913, the top one-half of one percent of the American people held 40 percent of the nation’s wealth. Many Irish Catholic workers held the erratic notion that that was not a democracy. That did not make them radicals. It does, however, make than subtle, if unconscious, subverters of Protestant America’s regnant values. That’s not the standard interpretation which holds that the unlovely features of America’s mines, factories, and foundries radicalized–or, at least, politicized–the American working class. America didn’t make them dissident. Neither did Marx. Ireland and their historically derived culture did it. Which makes Irish history an important part not just of American “working-class identities” but of everything in American history where an Irish Catholic influence was felt and can be shown. That is a major part of what I call my reinterpretation by accretion.

In History’s Erratics, IrishCatholic dissidence and thus cultural divergence seems to make them exceptions to the typical U.S. working-class history. While other groups might have aligned with dominant Protestant social norms or joined broader industrial labor movements to become more “American,” your erratics seemingly resisted this path. As you demonstrate, they subverted American capitalism, but also helped transform it in spite of their continued Irishness. From this perspective, how might History’s Erratics inform a broader understanding of American social history, particularly with respect to the influence of ethnicity, religion, and class in the development of American capitalism?

I’m not sure they were an “exception to the typical U.S. working-class history,” or that there is a “typical American working-class history,” or even that there was a “typical American working class.” Those hypotheses would have to be tested by other deep dives into the culture of the other major ethnic components of American labor to see if those others did, in fact, “align with dominant Protestant social norms . . . and become “more American.” To a certain extent, all of this country’s immigrant and ethnic workers “aligned” with American society; they lived in it. They had no choice. Similarly, all “became more American” or, at least, less of what they were. My analytical framework, however, is Irish Catholic worker culture that arose before they entered the American working class. That culture arose from Irish history and was passed down through the generations. Parts of it, in the words of Robert Orsi, were “almost inherently subversive” of the values of modern capitalist America. “Subversive” did not always mean ideologically radical, but clearly being subversive is an advance on being merely “erratic” or “dissident.”

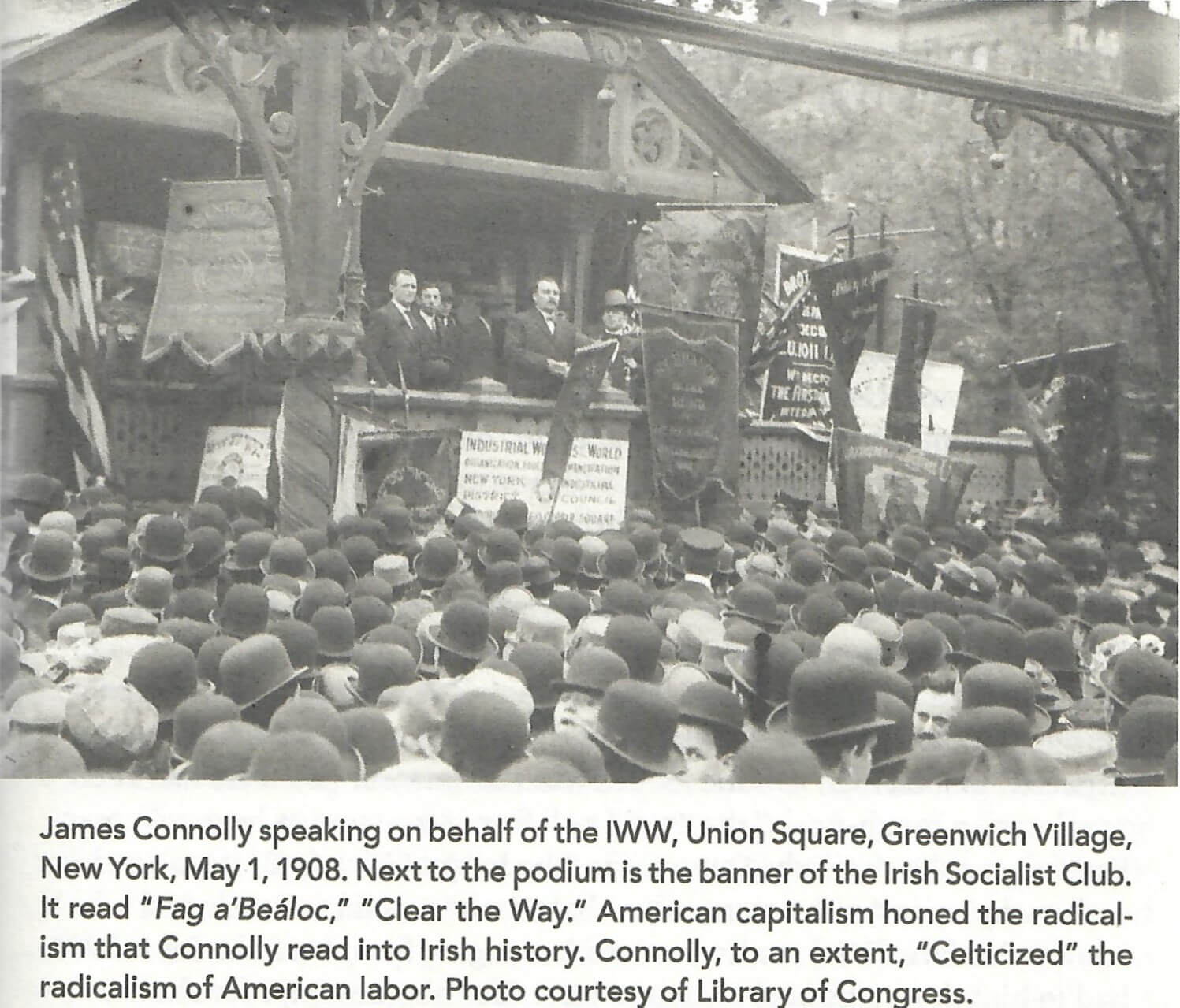

Mention should also be made of the aggressive rhetoric and actions of Irish nationalists and the pugnacious language of Irish nationalists in America. Anger was part of the stock in trade of both. So was organizing for angry purposes. Add now the language of James Connolly, also central to my main point: “The cause of Ireland,” he said, “is the cause of labour; the cause of labour is the cause of Ireland. They cannot be dissevered.” Marx, Engels, and Lenin, among others, had good reason to try to recruit Irish republican nationalists into the advance guard of anti-capitalism and anti-imperialism. It was not the Irish’s advanced theoretical understanding that commended them; it was their bandit tendencies. E.P. Thompson, joined by Eric Hobsbawm, agreed.

A word about why I chose “transformation” for my subtitle. One reason was because of Jackson Lears’s use of the word in the context of culture in his No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture. Another was the title of Karl Polanyi’s book The Great Transformation. Together, Lears and the “team” of Polanyi and Conrad Arensberg provided me with points of entry, Lears into American culture, Polanyi and Arensberg into Irish Catholic culture and the challenge to American capitalist values that it posed.

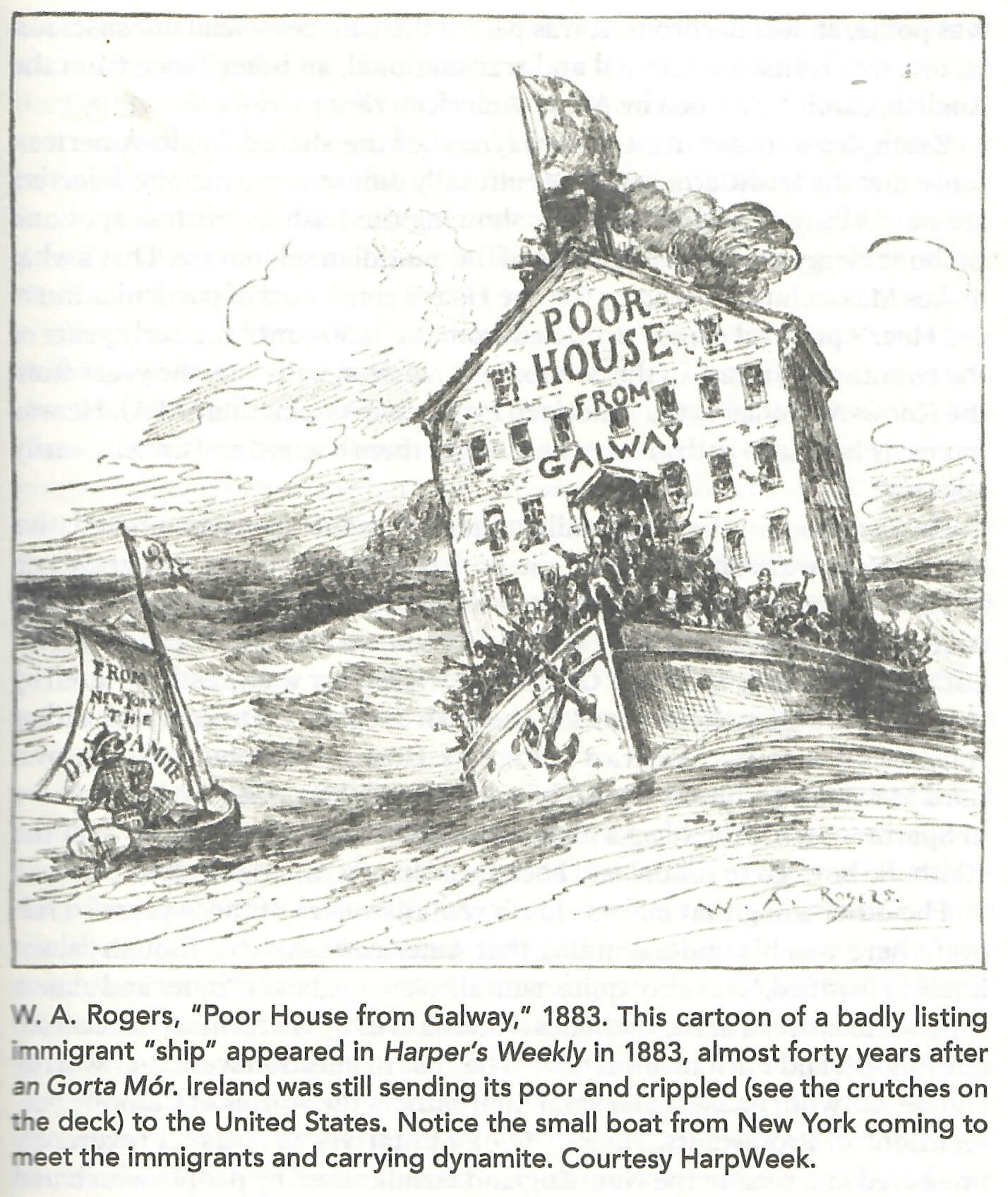

Put as briefly as I can, Irish Catholic dissidents in America, both immigrants and their near descendants, came from societies in which the economy was “embedded in” (Polanyi’s words) and subordinate to society. Irish townland economies were based on reciprocity; they were ones where those with bread shared it with those without on the safe assumption that the favor would be returned. The society of modern capitalist America, on the other hand, was “embedded in” and subordinate to a markets-driven economy; bread went to those who could pay the asking price. That depended on wages which depended on labor markets, and the price of bread, which depended on commodity and transportation markets. Laissez-faire–leave the markets alone; let them work their magic unhindered. In such an economy, hunger could easily be made a weapon of class war. Or, as the Irish knew well, a weapon in colonization policy.

The topic and timeframe of History’s Erratics brings another important labor history to mind – David Roediger’s Wages of Whiteness. In some ways your work picks up where Roediger left off by covering the period from the Civil War to the New Deal and arguing that working-class IrishCatholic dissidence helped drive the transformation of American capitalism through the Great Depression. Can you explain how History’s Erratics may or may not link up with Roediger’s conclusions about working-class whiteness in the antebellum period? Moreover, what are some of the key differences between IrishCatholic working-class experiences and those of other immigrant groups in America between 1870 and 1930?

I dealt with Roediger’s excellent book in some detail in my earlier Beyond the American Pale. I’ll summarize here: There were also “wages of Protestantism.” (In Butte, I found something that looked suspiciously like the “wages of Irishness”). All of those “No Irish Need Apply” notices contained an unstated sectarian adjective: No Irish Catholics need apply. The applications of the self-identified “Scotch-Irish” were welcome. It was papists who needed not apply. That American nativism and the IrishCatholic response to it were among the sources of an evolving–and dissident–IrishCatholic culture is one section of my “cultural turn.”

That, however, is as far as the “linkage” between the wages of Protestantism and Roediger’s book can be taken. I am not making an argument that American anti-Catholicism was even remotely as fierce, as constant, as cruel, as violent, as destructive, or as omnipresent as American racism. Mine is not an argument for a “critical [ethnic] theory.” Critical race theory, as I think Roediger employs it, is an indispensable analytical tool in American labor history. So is an understanding of the specific cultures of America’s immigrant/ethnic labor force.

Your epilogue ends the book on a fascinating discussion of Irish American responses to the Irish War of Independence, the emergence of the Saor Stát, and the Irish Civil War. One cannot help but notice the sharp contrast between the outcomes they observed in Ireland and faced America. On the one hand, many felt the Irish bourgeoise-led “Freak State” was a product of shoneenism, one totally devoid of the aspirations revivalists, republicans, and the laborite left held for an independent Ireland. On the other, America responded to IrishCatholic opposition and the Great Depression with the New Deal, thus creating the possibility of a more humane existence for many working-class people. Given these very different outcomes, would you say that IrishCatholic cultural divergence and working-class opposition actually pushed Gilded Age America away from developing into a “Freak State” of its own? Taking the point further, how might this history help us understand the current state of the labor movement, American capitalism, and U.S. politics?

I love those very leading questions! But let me first challenge a couple of their assertions. The Free State was not “totally devoid” of the hopes of the cultural revivalists and republicans on your list of “Irish dreamers.” The economy of the Saor Stát was never quite American capitalism writ small. Ireland after 1923 was never quite a cultural wasteland. Your question also gives too much credit to “IrishCatholic opposition” for the development of ideas of “moral capitalism.” (And that from someone who read and approved of “how the Irish saved civilization”!)

Polanyi in his The Great Transformation writes that the decades-long transformation from traditional, non-market economies to modern and capitalist ones was never unchallenged. There were always, and contemporaneously, countervailing forces. Polanyi called them the “double movement.” He doesn’t list Irish Catholics among them, though he comes close and I don’t think he would have objected to my inclusion of them.

They were among the many movements–and IrishCatholic dissidence had many of the features of a “movement culture”–that “pushed Gilded Age America” away from the bourgeoise “shoneen” state it had become. I would even point to the New Deal’s Federal Art Project. FDR didn’t just take lessons from Pope Pius’ 1931 labor encyclical “Quadragesimo Anno;” he admired the labor-themed murals that Diego Rivera had done for the “Detroit Industry” project. The Works Project Administration had a “poetic” as well as a relief function. It fused art and politics. The Irish Revivalists would have loved the WPA and its agencies; they kept artists, poets–and historians–fed.

Two of the things I most wanted History’s Erratics to do was change minds and the historical narrative on the idea that Irish nationalists in America wanted a free Ireland to look like America. Some may have–or may have said they did–but those on whom I focus both my attention and my affection most assuredly did not. I also wanted my book to correct the record: Irish Catholic workers in the U.S. were not hopeless reactionaries; they were not responsible for why “it,” as in communism, syndicalism, socialism, or a labor party, “didn’t happen here.” Indeed, they came closer than most (any?) to seeing that “it” would, or that “it” could have.

I also wanted my book to correct the record: Irish Catholic workers in the U.S. were not hopeless reactionaries; they were not responsible for why "it," as in communism, syndicalism, socialism, or a labor party, "didn't happen here." Indeed, they came closer than most (any?) to seeing that "it" would, or that "it" could have.

I am in complete agreement with Jackson Lears’s contention in his No Place of Grace that “the most powerful critics of capitalism have often looked backward not forward.” May I offer in evidence, Irish Catholic working people in capitalist America? I would grant that they were not keen on the idea of government ownership of the land and other “means of production.” Turning the economy over to the Irish’s governing “masters,” whether British imperialists or American capitalists, was not the solution. As for collectivized agriculture, the Irish, like those of “peasant’ background everywhere, saw that as little more than the renewal of serfdom. Besides, it was never socialism that they rejected, but socialists–the many anti-Catholics among them most prominently.

Finally, you ask what History’s Erratics says about the “current state of the labor movement, American capitalism, and U.S. politics.” It is important to keep in mind that beginning in the 1930s, IrishCatholics began to shed their erratic ways as Protestant America began to shed a small portion of its nativist “race patriotism,” the Kennedy 1960 campaign notwithstanding. But keep also in mind that I’m writing this on December 23, 2024!; the current state of everything that counts for something, I can only describe as somewhere between uncertain and perilous.

IrishCatholic pre- and anti-modernism and the pre- and anti-capitalism that went with it, what John Gaddis called their “personality as ecology,” made internal exiles of them. The Resistance to MAGA or DOGE politics (other than letting them devour one another) could learn something from that. Granted, the men and women in Lears’s No Place of Grace, like the present Resistance, were self-consciously antimodern. Their antimodernism was itself a form of modernity. They were acting out a role. I’m of the mind that the unintended IrishCatholic version of antimodernism was more authentic. I’m even tempted to say Irish dissident ways arose “organically.” They were not playing a role, they were in the role. I also admit, regretfully, that there may be no unintentional erratics left in America.

Fortunately, being intentionally out of time and out of place–anti-modernism as a conscious act of dissidence–might become a Polanyi “double movement.” (I will leave untouched that this would be a post-modern rather than an anti-modern double movement). IrishCatholic erraticism could be the antecedent of a new form of political and cultural resistance. The “current state” of American labor, American capitalism, and American politics–not to mention Americans’ self-identity, civility, sense of justice, and moral purpose, and knowledge of and attentiveness to history–are in serious need of some erratics’ help, even if the erraticism be more self-conscious and “contrived” than that of the Catholic Irish I wanted to describe.