Introduction:

An injury to one is an injury to all. Motto of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union.

In the past four decades, the American labor movement has seen dwindling union membership and incessant threats from corporations and government along with rightwing anti-union activists seeking to eliminate collective bargaining and other worker rights protected by union membership. This recent labor history proves instructive in understanding today’s seeming upsurge in union activism and organizing advances on several fronts.

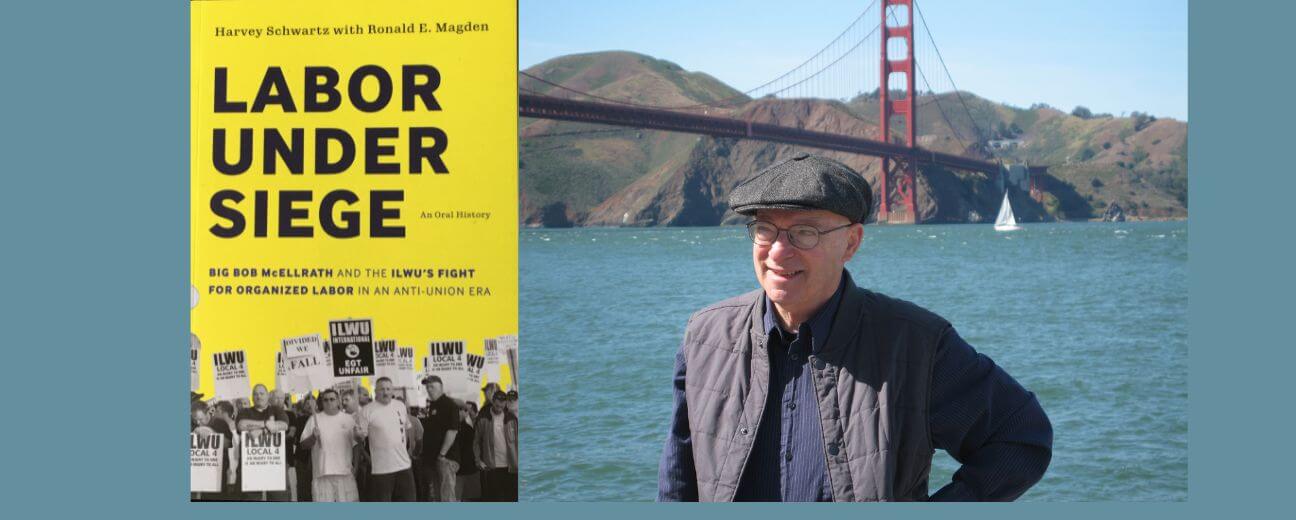

In the fraught years since the onset of the Reagan administration, the West Coast’s progressive International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) has persisted and achieved significant victories for members while experiencing some difficult compromises and setbacks. Labor historian Harvey Schwartz illuminates the work of this powerful labor organization and modern worker activism in his recent book of oral history, prepared with the late Ronald E. Magden, Labor Under Siege: Big Bob McEllrath and the ILWU’s Fight for Organized Labor in an Anti-Union Era (University of Washington Press, 2022). By delving deeply into one prominent labor organization, the book reflects the conflicts and constraints that have threatened the existence of American unions in recent years.

Dr. Schwartz’s study focuses on the career of the resolute and charismatic union leader Robert (“Big Bob”) McEllrath, who served nearly four decades as an ILWU official, including as International vice president from 2000 to 2006 and International president from 2006 until late 2018. The book traces the story of this legendary six-foot-four champion of working people from his youthful athletic achievements to the beginning of his career on the docks in Vancouver, Washington, in 1969, and through his varied work duties and his increasingly responsible union positions since 1980, concluding with his service as ILWU president and his retirement from active union engagement on January 1, 2019.

Dr. Schwartz and Ron Magden interviewed McEllrath and 40 other coworkers and union colleagues, as well as family members, to create this insightful and engaging working-class history. The interviewees flesh out McEllrath’s evolution from dockworker to union leader and describe many significant labor-management confrontations during those years. Dr. Schwartz, an expert on the ILWU and union history, organizes the book around themes and events that he has researched and written about for decades, and his special knowledge and exhaustive research shine through this oral history.

From the interviews of colleagues and others, McEllrath emerges as a visionary strategist with a gift for complex negotiations and a reputation for integrity, honesty, transparency, and courage in the face of pro-employer laws, employer recalcitrance, rightwing anti-union activists, dire threats, and even physical violence.

As he led the union, McEllrath never lost sight of the progressive ILWU traditions of inclusion, equality, democracy, and social justice. He valued internal union democracy, equitable job distribution, militancy, international cooperation, and a diverse workforce. The union has represented workers from an array of backgrounds, including women and men of Black, Asian, Indigenous, Pacific Island, and other ancestries. And the union has famously challenged violations of human rights and worker rights by corporations that embrace brutal globalization and privatization practices.

According to contributors to Labor Under Siege, McEllrath had a record of more successes than losses in unifying and expanding the union as he bargained with often intransigent employers for better working conditions and recognition of worker rights. In an era when many unions were losing members and facing incessant anti-worker attacks, his successes were quite noteworthy, including wage increases, better benefits, and reforms to advance social justice and fairness in hiring.

McEllrath’s legacy will inform the new generation of labor leaders who can look to his policies, strategies, and approaches to conflict as the labor movement now gains energy on several fronts.

Perhaps recent developments bode well for the future of American workers. Late September 2023 saw a historic moment as President Joe Biden became the first sitting president to join a picket line with striking workers, members of the United Auto Workers. The president donned a hat emblazoned with the UAW symbol and stood with UAW president Shawn Fain as he proclaimed his support for the workers and the labor movement. The following day, former president Donald Trump visited a non-union factory and proclaimed his love for workers as he failed to acknowledge his notorious antagonism toward labor unions and his trickle-down economic policies that hurt working people while benefiting the wealthiest citizens and large corporations. It’s certain that Big Bob would have some astute comments on Trump’s rather constricted “love” of workers and his loathing of unions that protect employees.

Dr. Schwartz’s Labor Under Siege will stand as an important contribution to the recent history of workers. It provides a context for working-class and social justice studies as it informs and inspires today’s workers, activists, union leaders, and all citizens who value justice, fairness, and democracy.

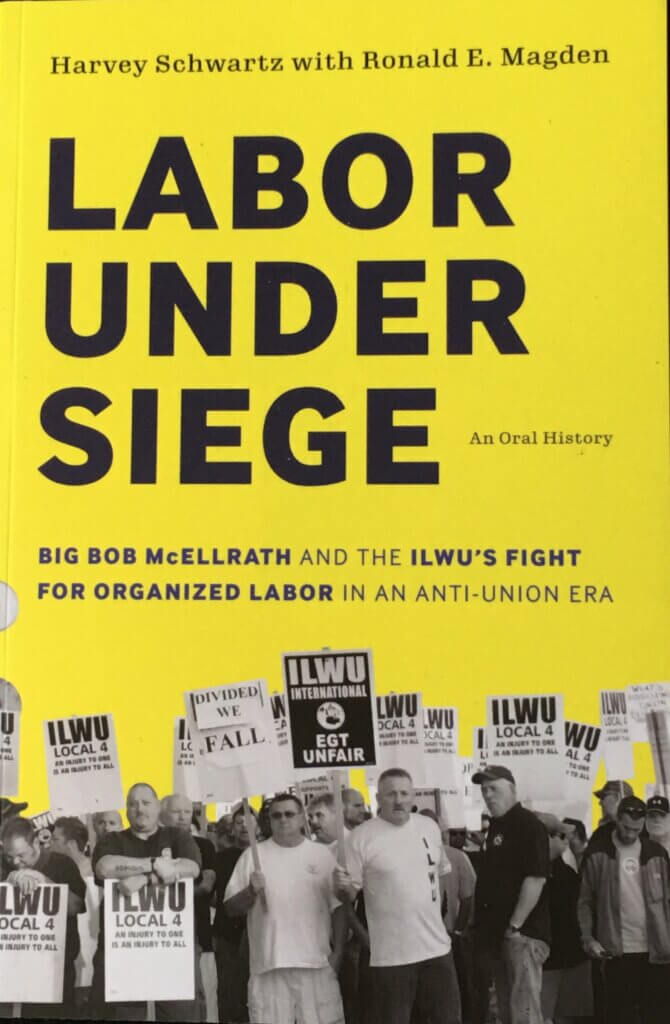

Dr. Schwartz is curator of the ILWU Oral History Collection at the union’s library in San Francisco. He wrote Labor Under Siege with his friend and colleague Ronald E. Magden (1926–2018), the author of several books of labor history, including A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers, 1884–1934, and two volumes about dockworkers in Tacoma, Washington. Their new book recently won prizes from Independent Publisher Book Awards, National Indie Excellence Awards, and Nautilus Book Awards, and was a finalist for an Independent Publishers of New England Award. Dr. Schwartz’s other books include The March Inland: Origins of the ILWU Warehouse Division, 1934-1938 (1978; rpt. ILWU 2000); Solidarity Stories: An Oral History of the ILWU (2009); and Building the Golden Gate Bridge: A Workers’ Oral History (2015). He holds a Ph.D. in history from The University of California, Davis.

Dr. Schwartz graciously responded to a series of questions by email.

Robin Lindley: Congratulations Dr. Schwartz on your new book Labor Under Siege on the International Longshore and Warehouse Union and the leadership of Robert “Big Bob” McEllrath. Before getting to the book, I wanted to first ask about your background. What sparked your interest in history and then your decision to specialize in labor history?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: I got interested in history when I took a class in Western Civilization as an undergraduate at Stanford. I thought, “Wow! History is the key to understanding everything.”

Later, when in the Army, I was stationed in South Texas. It was the 1960s. Most white Texans I encountered hated the Civil Rights Movement. What I saw and heard in South Texas disturbed me profoundly.

After the Army, I joined a civil-rights group, studied US social and political history in an M.A. program at the University of Washington, and decided that the best hope for most Americans remained the labor movement, despite its shortcomings and challenges. I thought maybe I could contribute by becoming a labor historian. I completed my M.A. and moved on to study for a Ph.D. in U.S. history at the University of California, Davis, with the eminent labor historian David Brody.

Robin Lindley: Did you ever work on the docks or at other demanding labor? Was your family connected with the world of longshore or warehouse work?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: I was never a dock or warehouse worker. I’ve had a few physically demanding jobs though. I once worked in the woods near Seattle, splitting logs and loading and unloading them for a firewood distributor. We used long-handled, double-bitted axes. You had to swing them in a certain way to make them work right. This job was more dangerous than I realized at the time. As a kid, you sometimes don’t think of such things.

My parents were not associated with the ILWU, although growing up in San Francisco I often heard about the union. I really discovered its progressive history and culture in depth when I read a fellow UC Davis graduate student’s paper on the 1934 West Coast maritime strike. He did not go on to study the ILWU, but I became fascinated by the organization. I did some research and quickly decided to write my dissertation on some aspect of the ILWU. Later that became a book entitled The March Inland: Origins of the ILWU Warehouse Division, 1934-1938 (1978, rpt ILWU 2000).

Robin Lindley: You are a renowned oral historian. How does that approach differ from a traditional narrative history or other forms of historical research and writing?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: I’m not sure about that renowned label, but I think I can answer your question. Oral history brings immediacy, vitality, and authenticity to any historical account. Often it can provide insights and answers you cannot find through traditional research. Many oral histories are also accessible, which widens the audience for such works.

Still, to do oral history correctly, you have to ground your work in the traditional research any historian does. Reading primary and secondary materials in archives and libraries remains important for oral historians. You have to be well prepared before you can ask the right initial questions and pose informed follow-up inquiries. Mastery of the surprisingly demanding techniques of oral history interviewing is also key if you want to learn all you can from the people you speak with.

Robin Lindley: For historians and others who may have an interest in oral history do you have some basic pointers on how to prepare and present oral history interviews? Are there a few resources that may be helpful for novices?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: I became an oral historian by necessity. In the early 1980s, the ILWU hired me to conduct interviews when the union won a National Endowment for the Humanities grant to record veteran members. I’d written a book about the ILWU that included quotes from interviews, but I was not yet a real oral historian. So, I read everything I could find on oral history methodology. That’s obviously one useful way to get started.

As to basic pointers, you want to approach an oral history interview with an informed question list in hand, listen for clues to additional questions, refrain from interrupting or arguing with your interviewee, use good recording equipment—especially decent microphones—and back up your recorded discussion in a proper archive. The gold standard for an oral history, too, has long been the “full life history,” which means asking questions that explore an interviewee’s life from childhood to retirement.

In preparing oral history material for publication, you want to retain the meaning, tone, and style of your interviewee. What I mean is that you can’t alter what people say or how they speak. There is more to it than that, of course. Fortunately, today there are several good “how to” books available. Doing Oral History, a classic by Donald A. Ritchie, is still among the best. Another good one is Valerie Yow, Recording Oral History.

The world’s leading practitioner over the last several decades has been the Italian oral historian Alessandro Portelli. He can analyze the meaning beyond what is said on the surface far better than most of us. For examples of the potential of oral history I’d recommend his books to anyone, perhaps starting with The Order Has Been Carried Out: History, Memory, and Meaning of a Nazi Massacre in Rome and They Say in Harlan County: An Oral History. More advanced oral historians can benefit from joining the Oral History Association and subscribing to its journal.

Robin Lindley: Thanks for those pointers and resources. Your new book deals with the recent history of the ILWU from the sixties or so almost to the present with a focus on the work of Robert “Big Bob” McEllrath, who held leadership positions in the union for almost three decades and then served as union president from 2006 to 2018. What inspired you to take on these themes for this book on labor history?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: The ILWU Oral History Project that was originally funded by the NEH has functioned almost continuously since the early 1980s. With 400 interviews, it is the longest-running and largest oral history project in the United States maintained solely by a labor organization. All of the interviews are digitized and stored at the union’s International library in San Francisco. I have been fortunate to be part of the project since its beginning.

Solidarity Stories: An Oral History of the ILWU, a book I wrote fifteen years ago, is based on the ILWU collection. Interviewing McEllrath and other ILWU activists about the union’s recent history was a logical extension of the ILWU Oral History Project’s work. That McEllrath was president for so long and presided during particularly volatile and challenging years in the union’s history made investigating his era especially interesting. It also made sense to have Ronald Magden, an expert on the ILWU in the Pacific Northwest, participate in preparing the McEllrath book. This was something McEllrath advocated for. Ron and I worked together closely from 2013 until he passed away in late December 2018.

That there are few biographies of recent American labor leaders or histories of what a mature union is like today and how it functions helped inspire us in our work. So did the opportunity to show readers how a progressive labor union could survive against the kinds of threats most US unions have faced over the past thirty or forty years.

Robin Lindley: What was your research process for this oral history of the modern ILWU?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: We wanted this history to cover the union’s recent past as well as McEllrath’s career. Featuring multiple voices seemed necessary to produce a full picture of the union’s experience. In addition to interviewing McEllrath several times, we recorded forty union officials, the ILWU’s long-time attorney, rank-and-file union members, McEllrath’s wife Sally, some overseas longshore unionists McEllrath worked with, and even McEllrath’s high school basketball coach.

To inform ourselves in our interviewing and writing, we still did traditional historical research, including union, mainstream, and business newspapers and journals, ILWU convention proceedings, union contracts, primary documents in archives, and relevant secondary accounts. Over many years, too, I have benefited greatly in my oral history research, transcribing, and writing through aid from the union’s International officers, newspaper editors, and directors of educational services, librarians, and archivists, especially Carol Cuenod, Gene Vrana, and Robin Walker. From 2013 on Ron and I profited as well from doing oral history interviews for the union’s Pacific Coast Pensioners Association Oral History Project, which houses its recordings at the archives of the labor history of Washington State at the University of Washington. Conor Casey, the archivist there, helped us in many ways. Quotes from ten of the forty-one people interviewed for Labor Under Siege came from recordings done for the PCPA project. The other thirty-one interviews are stored in what is now called the ILWU Oral History Collection at the union’s International library in San Francisco. Ron and I also benefited from editorial advice from the University of Washington Press staff and from the press’s peer reviewers, Peter Cole and Erik Loomis.

Robin Lindley: How would you introduce readers to the now legendary labor leader McEllrath? What are a few things you found that shed light on his early work experience and his evolution as a union leader?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: Even before he became ILWU International president, McEllrath worked to cultivate the widest internal unity possible in the union’s West Coast Longshore Division, its core entity, and in Hawaii, the location of its biggest general industries local. This, plus his charismatic personality and speaking ability, gained the trust of the majority of the union’s regional officers and rank-and-file members. These attributes helped McEllrath gain a big following in the union despite his coming from a small Pacific Coast port.

McEllrath also became a shrewd negotiator in office. He was good at anticipating other people’s moves. McEllrath approached negotiating as the art of the possible. Sometimes what was possible was limited, but he persevered, always with an eye to getting the best deal he could and to preserving his union in the face of challenges, some existential, during a dangerous period for all American labor organizations.

Finally, as a former high school basketball star, boxer, and skilled longshore worker, McEllrath had physical courage and internal fortitude. In 1985, while a young local leader, he personally led an ILWU rush into an employer lumberyard to protect the union’s threatened jurisdiction. Twenty-six years later, when International president, he faced down the police during a particularly tense confrontation. These incidents and others enhanced McEllrath’s status in the ILWU for the large majority of the union’s members and helped get him elected International president four times.

Robin Lindley: Thanks for that background. How did McEllrath come by his progressive attitudes on race, equality, democracy, internationalism, and social justice issues, and how did he weave those attitudes into his union leadership work?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: The ILWU has a long tradition of support for racial equality, equal access to work, union democracy, internationalism, and social justice going back to its beginning in the 1930s. Harry Bridges, the union’s founder and its president for forty years, was a progressive who was long identified with the left. He seemed a radical in his time and, because he was an Australian immigrant, he was threatened with deportation between 1934 and 1955 supposedly as an alien Communist. He survived all of his many legal cases, including two that reached the United States Supreme Court. Bridges, and the many ILWU people who supported him, put their progressive stamp on the ILWU and it is still there. Last year Robert Cherny published a great new biography of Bridges.

For his part, McEllrath joined a union that had an established progressive legacy. He came from a small Pacific Northwest port that did not have many minority group members. Regardless, he had a powerful sense of fairness that governed his thinking and served him well throughout his career. He encountered a few challenges over minority issues early on but worked to overcome them.

McEllrath also respected the union’s tradition of union democracy throughout his long service as International president. He consistently avoided forcing his own views on delegates from different locals during the union’s crucial Longshore Division caucuses held before ILWU negotiating demands were voted on and finalized. McEllrath had the power to sway people, but typically only commented at any length on issues when he felt it was absolutely necessary after all attending delegates had spoken. He then accepted the results of union votes, regardless of his preferences.

McEllrath’s support for internationalism followed in Bridges’s tradition, although his focus was a bit narrower since it prioritized cultivating close alliances mainly with overseas waterfront labor organizations. McEllrath was not always seen as a fiery social justice activist, but here again his sense of fairness came into play. Like most ILWU leaders, he sometimes turned out to support the picket lines of other unions and occasionally went to jail briefly for his actions. Basically, he succeeded in working within the union’s legacy.

Robin Lindley: Fellow union officials and others interviewed for your book praise McEllrath’s leadership and offer mostly positive comments on his charisma, calmness, thorough preparation, strategizing, ability to unite workers, loyalty to workers, courage, toughness, and more. How do you see his strengths and weaknesses as a labor leader?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: We have touched on a number of McEllrath’s strengths already. Regarding preparation, Rob Remar, the union’s longtime lawyer, describes McEllrath’s unusual strength in that regard vividly in Labor Under Siege.

Concerning weaknesses, or at least criticism, while McEllrath was generally viewed as a strategic negotiator who was good at anticipating employer moves, a few people have questioned some of McEllrath’s compromises in certain contract negotiations and his reluctance to take big, expensive, multi-year gambles in organizing beyond the union’s core entity, its Longshore Division. But in his time in office, before there appeared to be a resurgence of American labor, he made decisions he viewed as necessary to preserve the ILWU in an anti-union era when hardline corporate executives, numerous politicians, most police authorities, many vocal representatives of the media and the public, American labor law, and even a few other unions were arrayed against him.

Robin Lindley: You detail many situations where McEllrath’s canny leadership worked to the benefit of fellow ILWU workers as the union’s membership and influence expanded. I was struck by his dealings in 2009 with the employer Rio Tinto, a large international firm with a record of human rights violations, environmental disasters, and brutal suppression of union activities. Despite the company’s tenacious resistance, McEllrath was eventually able to bring into the union Rio Tinto employees who were borate miners in rural California. How do you see this difficult situation and McEllrath’s strategy to achieve an agreement with this intransigent employer?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: The Rio Tinto miners came into the ILWU in the mid-1960s. They were already members of the union when Rio Tinto locked them out for 105 days in 2010.

In any case, your characterization of the company is quite accurate. During 2009-2010, Rio Tinto offered the union a contract with drastic takeaways it could not accept. When the miners resisted, the company hired strike breakers, secured police protection, and blocked the ILWU workers from entering its facility. As local negotiations dragged on, the ILWU International office sent its dynamic organizing staff to Boron, the mine’s isolated location in the Mojave Desert, to help fight the lockout. McEllrath monitored field operations from the ILWU International office in San Francisco. Meanwhile, the ILWU enlisted aid from other unions and community organizations to put pressure on the company.

Late during negotiations, when the timing was right, McEllrath went to Boron. He had to negotiate with his union’s local leadership and with Rio Tinto’s people as well to get a contract, but he succeeded. The contract was not perfect, but it was far better than no contract or what the company had initially proposed. The whole story is more colorful than I am making it sound. I think it is better told in the words of McEllrath and others in the book, but you get the general idea.

Robin Lindley: McEllrath also demonstrated savvy and courage in 2011 during the extremely contentious and prolonged dealings with Export Grain Terminal Development (EGT) in Longview, Washington. In an effort to unionize granary employees, McEllrath led worker protests including blocking a grain train from its destination. Police violently attacked protesters, and the press and local officials as well as the US Coast Guard in southwest Washington aligned against the union for disruption of EGT’s work. Union members and protestors were arrested and jailed. Eventually, McEllrath was tried and briefly jailed. Why did this labor dispute become so vitriolic, violent, and prolonged? What was McEllrath’s strategy to eventually attain an agreement that was mostly favorable to the ILWU?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: EGT is a powerful multinational joint venture. In 2011, it opened a new 200-million-dollar grain terminal in the Pacific Northwest port of Longview, Washington. Grain handling is big business. A third of all U.S. grain exports go through Northwest ports.

The ILWU maintained a contractual relationship with long-established Northwest grain companies dating back to the 1930s. This contract was important to the union’s whole Longshore Division. Anticipating good union jobs, ILWU waterfront workers in Longview initially lobbied for EGT to come to town. Later EGT refused to recognize the ILWU. Instead, it ignored the ILWU’s historic role in the grain industry and gave a contract to a rogue local of another union.

Incensed, Longview ILWU workers and their supporters demonstrated against EGT and actively resisted its behavior. McEllrath, who knew bulk grain work from his days on the Vancouver, Washington, waterfront, took a brave stand in personally confronting the police during a day when officers savagely attacked ILWU demonstrators. For weeks afterwards, the police in Longview terrorized and detained ILWU members. Throughout the whole EGT struggle, police officers manhandled and injured a number of people, including some women seniors who backed the union.

The EGT confrontation was long and bitter because the union battled back against a company it saw as grossly unfair and a threat to its jurisdiction in the Northwest grain industry, and because EGT enlisted the police and other authorities on its side and doggedly dug in its heels. Six months into the struggle the Coast Guard threatened to open fire on ILWU pickets if they blocked a grain ship headed for EGT’s terminal on the Columbia River. Catastrophic violence was avoided when the Washington State governor brokered a deal between McEllrath and the company. The deal covered EGT production and maintenance people, but it also set up a pool of employees who would work incoming vessels and trains as needed for twelve-hour shifts. McEllrath said, “EGT got some employer rights, how they can hire you, which sticks in my craw.” Still, the rogue union’s workers were dismissed and ILWU employees entered the EGT plant. Although the agreement was not perfect for the ILWU, the union gained jurisdiction at EGT and shored up its position in the Northwest grain industry.

Robin Lindley: You bring this intense situation with EGT to life in your book. You also point out that many disputes between the ILWU and employers involved automation and modernization in the workplace. And, for decades, employers have had the right to implement “work-saving” machinery and technology. How do you see these concerns as unions are dealing today with developments at warp speed with automation, robotics and even internet technology? How can unions continue to keep members as technology threatens many positions?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: Historians are trained not to predict history because no one can. There are generally too many unknown variables in play. Of course, automation can hurt unionized and other workers who lose decent jobs to “the machine” and never get them or anything similar back despite promises from various quarters.

Unions can fight technological change. The Luddites did so, sometimes violently, in the early nineteenth century, but as the great English historian E. P. Thompson wrote, “Luddism ended on the scaffold.” Fifty years ago, the East Coast-based International Longshoremen’s Association resisted containerization when it was new. But the ILA could not forestall the “container revolution” and ultimately accepted the new cargo handling method. The West Coast–based ILWU, on the other hand, negotiated to accept containerization in 1960 in exchange for various concessions, including job guarantees and inducements for early retirement.

The union’s first contract in 1934, granted through federal arbitration of the great strike of that year, said the employers could introduce labor-saving devices. No one then could imagine what that precedent might mean decades later. Regardless, since the 1960 contract was signed, the ILWU has steadfastly held that when technological change threatens jobs, the union will negotiate to get what it can while the getting is good and will insist that any new jobs created in the place of old ones remain ILWU positions. There are critics of that approach as not doing enough, although McEllrath employed it consistently with some success when computerization and mechanization threatened certain waterfront jobs. Maybe this approach could work for other unions seeking to hold on to members in the face of anticipated technological upheaval. Admittedly, it is a partial solution to what seems poised to become a major social problem, but perhaps it can help in the right cases.

Robin Lindley: McEllrath and other union officials stressed the ILWU’s commitment to advancing social justice. A good example you share is the union’s support of Indigenous Americans at Standing Rock, North Dakota, who were opposed to completion of the Dakota Access Pipeline that threatened Native natural and cultural resources. How did the union become involved in this protest and what assistance did the union provide? What was McEllrath’s role?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: The ILWU’s celebrated support of social justice causes goes back to its beginnings in the 1930s. During the great West Coast maritime strike of 1934, Harry Bridges famously insisted that the union local in San Francisco, then the coast’s biggest port, commit to the hiring of Black workers on an equal basis with whites. This was a unique stance then.

Despite some early local resistance, the union has continuously championed Black rights and the rights of other non-white workers over the years. Since 1969, the membership of the union’s local in San Francisco has been more than fifty percent African American. This is all well documented and reasonably well known. Recent examples exist in the writings of historians Robert Cherny and Peter Cole.

When I conducted interviews for the McEllrath project, the Standing Rock protest movement emerged. It was the biggest gathering of aggrieved Indigenous Americans in years. I decided to ask questions about the union’s support for Standing Rock as a good example of the continuation of the union’s legacy of backing social justice causes. When I asked McEllrath about this, he said, “We’re still social justice, absolutely. We’re always trying to help, especially, you might say, the underdog.”

It was other people in different ILWU locals who took the first steps toward aiding the Indigenous Americans by going to Standing Rock to join the protest there, bring in supplies, and help build shelters in cold conditions. The ILWU International Executive Board and the union’s Coast Longshore Committee donated thousands of dollars. Finally, at the union’s International Convention in 2018, with Standing Rock in mind, McEllrath introduced a resolution to streamline how the union could more quickly allocate substantial donations to worthy social justice causes. It passed easily.

Robin Lindley: Although some unions are gaining ground today, it seems that most unions are facing innumerable challenges from modernization to anti-union sentiment in many parts of the country. What lessons can workers and other unions take from the story of the ILWU and the leadership of Big Bob McEllrath?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: In Labor Under Siege, I wanted to use the ILWU’s experience to show how much and for how long American unions have been under attack and forced into a defensive position. When the book was in press, it was not clear that there would soon be a labor organizing upsurge in the United States. There were a few stirrings in 2020-2021, but something like the organizing progress and union militancy of “Solidarity Summer 2023” could not be predicted.

In Siege, I emphasized obstacles to organizing that faced the labor movement, including how labor law has favored anti-union employers since the passage of the 1947 Taft-Hartley amendment to the 1935 National Labor Relations Act. An August 2023 decision by the National Labor Relations Board should make it easier for unions to organize. That kind of progress did not seem likely just two or three years ago. But even if it becomes harder for employers to resist organizing drives, under current labor law they can still indefinitely refuse to agree to contracts. And under the current US labor relations system, getting a contract remains where the rubber meets the road.

Certainly, the organizing sweep of the last few years has been inspiring. But so far, the many newly organized workers across the country have been unable to convince recalcitrant executives in powerful corporations like Amazon and Starbucks to concede contracts. Yet there remains a chance that this could change for the better. After firing unionists and stalling for a long time, in early 2024 Starbucks officials finally said they would talk to their organized employees. That could hold some promise.

As to lessons for other workers and unions, I think the ILWU’s tenacity and perseverance can be an inspiration. I submit, too, that the ILWU can serve as a model of how a historically progressive union with a strong tradition of union democracy, inclusiveness, and social justice can carry on even under adverse conditions. I argued this position fifteen years ago in the introduction to the oral history of the ILWU I published then. I still believe that.

As to organizing, after the ILWU lost an NLRB certification election in 2008 at a big California agricultural processing company following an intense four-year campaign, McEllrath decided that costly, long-term organizing drives would not be undertaken again while he was president. McEllrath made that decision during the anti-union years that may have ended shortly after he retired from office. Now that the atmosphere for organizing has changed, with a large majority of Americans favoring unions for the first time in years, more ambitious approaches to organizing seem called for. Yet McEllrath’s careful attention to the preservation of his organization in dire times still holds valuable lessons for us all.

Robin Lindley: Is there anything you’d like to add about your work as a historian or about your new book or anything else for readers?

Dr. Harvey Schwartz: I think we’re good. Thank you very much for inviting me to answer your questions.

Robin Lindley: Thank you, Dr. Schwartz for your thoughtful comments on your life as a historian and your recent book, Labor Under Siege. Congratulations on this fascinating and detailed look at one of America’s most progressive and effective unions and the work of longtime union leader Big Bob McEllrath. I appreciate your illustrious career sharing the history of workers in America, and I think all citizens should learn about labor history to better understand working people and the benefits we’ve all gained from the labor movement that we often take for granted today. Best wishes on your book and your future projects Dr. Schwartz.

Author

-

Robin Lindley is a Seattle-based attorney, writer, and illustrator. He was features editor for the History News Network. His work also has appeared in Writer’s Chronicle, Bill Moyers.com, Re-Markings, Salon.com, Crosscut, Documentary, ABA Journal, Huffington Post, and more. Most of his legal work has been in public service. He served as a staff attorney with the US House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations and investigated the death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. His writing often focuses on the history of human rights, social justice, conflict, medicine, visual culture, and art. He is currently preparing a book of selected past interviews. Robin’s email: robinlindley@gmail.com.