In the United States there exists today, and has existed since at least the 1950s, a dominant political narrative according to which most Americans, indeed the very history of the country, exemplify a kind of ideological “moderateness.” Democratic Party operatives and sympathizers constantly preach the virtues of occupying the political center, where most of the population supposedly resides. If the party caves in to its “extremist” left wing, it faces electoral annihilation.

This narrative echoes, in a vulgar and opportunistic way, the postwar “liberal consensus” school of thought among social scientists and more generally the political culture, that the U.S. has historically been an exceptional country in its relatively middle-class and Lockean-liberal character, its individualism, its relative absence of dramatic ideological clashes, of class conflict and class consciousness. Louis Hartz’s The Liberal Tradition in America, for example, published in 1955, was a classic expression of this “centrist” interpretation of American history, an interpretation that tended to explain away and criticize what dissent there was—on the left and the right—as consisting of fringe movements of status anxieties, maladjusted psychologies, anti-intellectual impulses, hysterical moralism, and the like.

For the centrist establishments, then, of both the Cold War and today, left-wing (and right-wing) dissidence is simultaneously pathological and, in the broad sweep of American history, aberrational. The U.S. is essentially a middle-of-the-road, bourgeois country, which is why radical movements have usually failed and are doomed to failure in the present and future.

Since the 1960s, scholars have subjected this liberal creed in its various facets to devastating criticism, but it continues to hold sway, in some form, even among sophisticated academics who ought to know better. An early critique was given by Michael Paul Rogin in his brilliant The Intellectuals and McCarthy: The Radical Specter (1967), which systematically exposed the flaws in liberal analyses of “protest politics” (notably their assimilation of McCarthyism to an earlier tradition of agrarian radicalism, as if “irrational” left populism was to blame for McCarthy). Later scholars have shown that U.S. history contains just as much class conflict and class consciousness as the history of Western Europe; Sean Wilentz’s 1984 article “Against Exceptionalism: Class Consciousness and the American Labor Movement, 1790–1920” is a compelling statement of this point of view.

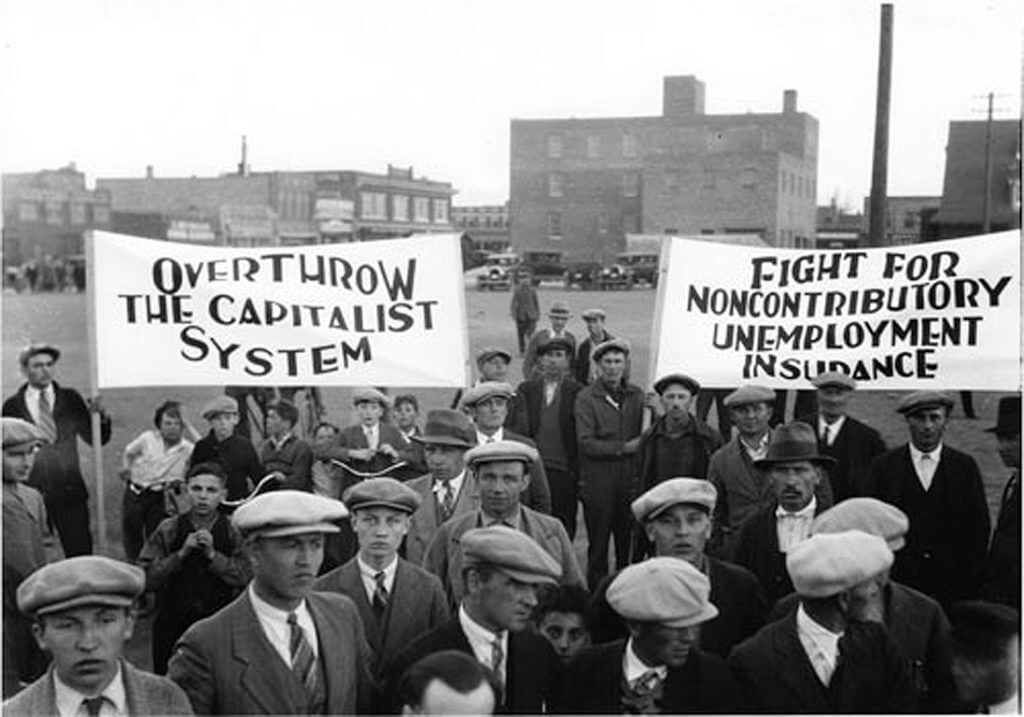

Recently, my own book Popular Radicalism and the Unemployed in Chicago during the Great Depression (2022) has criticized liberal analyses of the 1930s, which tend to dismiss the idea that there was much radical potential—socialist yearnings or revolutionary sentiment—in popular collective action of the time. Supposedly even in the 1930s, the quintessential “collectivist” decade, the American masses remained broadly subject to the hegemony of bourgeois culture, loyal to the distinctive U.S. political economy, and uninterested in radical social change. After all, they adored Franklin Roosevelt and rushed into the open arms of the Democratic Party in 1936.

Given that the political economy of the U.S. today has ominous parallels with the economy that eventuated in the Great Depression—including extreme income and wealth inequality, limitless aggrandizement of big business, and weakness of organized labor—it might be of interest to challenge such interpretations of American history, borrowing from my book. There is in fact an enormous base of support for truly radical change today, and there certainly was in the 1930s.

Historians influenced by the liberal tradition, such as, for example, the late Alan Brinkley, Jill Lepore, and Jefferson Cowie, tend to adopt a somewhat “idealistic” (anti-materialistic) perspective on society, to some extent abstracting from class conditions and class conflict in favor of an emphasis on culture, ideas, ideologies, and discourses. “The United States is founded on a set of ideas,” Lepore writes in her defiantly anti-leftist bestseller These Truths: A History of the United States (2018)—and of course the ideas in question are noble ideas: “a dedication to equality… [and] a dedication to inquiry, fearless and unflinching.” This is the way of the liberal (and many a conservative as well): to ground society in abstract ideas, preferably lofty ones, prioritizing “consciousness” over “social being,” as if Karl Marx hadn’t already shown in The German Ideology (1846) that the former is largely a sublimation (often obfuscation) of the latter. The idealistic method typically implies an ahistorical essentialism: the U.S. is “essentially” committed to equality and democracy, however rarely it may live up to “its” ideals—or it is essentially individualistic or anti-statist or capitalist or whatever other idea is favored. In abstracting from class conditions, idealism usually has conservative implications, which is doubtless why it has always been preferred by ruling classes and the intellectuals who speak for them.

Jefferson Cowie is more sophisticated and less propagandistic than Lepore, but he too, like many other excellent historians, is not always sufficiently materialistic. For instance, in The Great Exception: The New Deal and the Limits of American Politics (2016) he insists that Americans remained very “individualistic” even in the depths of the Great Depression, and that traditions of so-called individualism have contributed significantly to vitiating collectivist radicalism in the United States. Like other liberal scholars, Cowie seems to prefer explaining the defeats of the American left in terms of the stubbornness of various popular ideologies and cultures, including divisions among the working class (between race, ethnicity, skill, gender, etc., as if such divisions haven’t existed elsewhere), rather than the more basic and “material” fact that America’s capitalist class has historically been unusually ruthless, class-conscious, repressive, resourceful, and dominant over the state. This fact, indeed, is the real American “exceptionalism,” and it is the primary explanation for the failures of the left in the U.S.

As a case-study of popular consciousness, we might consider the remarkable nationwide support given to two famous left-wing “demagogues” of the 1930s, Huey Long and the “radio priest” Father Charles Coughlin. (Coughlin is sometimes called a fascist, but respected scholars have argued that this label isn’t appropriate for him until after 1937, by which time his popularity was vastly diminished.) Historians commonly interpret the massive popularity of these two figures as, ironically, proof of the relative conservatism of Americans. Cowie, for example, in a vague and idealistic formulation (disregarding class) characteristic of liberal historiography, states that these men and their following were very individualistic: they merely hoped “to restore the republic to the little man, resurrect some version of traditional values, and deliver the individual from the crush of mass society.”

Cowie’s interpretation echoes that of Alan Brinkley’s Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression (1983):

The failure of more radical political movements to take root in the 1930s reflected, in part, the absence of a serious radical tradition in American political culture. The rhetoric of class conflict echoed only weakly among men and women steeped in the dominant themes of their nation’s history; and leaders [such as Communists] relying upon that rhetoric faced grave, perhaps insuperable difficulties in attempting to create political coalitions. The Long and Coughlin movements, by contrast, flourished precisely because they evoked so clearly one of the oldest and most powerful of American political traditions [namely, “opposition to centralized authority and demands for the wide dispersion of power”].

But what did Long and Coughlin actually say? It is revealing to look at their words. While they both denounced Socialism and Communism, Coughlin thundered that “capitalism is doomed and not worth trying to save.” A journalist wrote in 1935 that he “talk[s] about a living wage, about profits for the farmer, about government-protected labor unions. He insists that human rights be placed above property rights. He emphasizes the ‘wickedness’ of ‘private financialism and production for profit.’” The principles of Coughlin’s National Union for Social Justice, founded in 1934, included the following: a “just and living [i.e., not market-determined] annual wage which will enable [every citizen willing and able to work] to maintain and educate his family according to the standards of American decency”; nationalization of such “public necessities” as banking, credit and currency, power, light, oil and natural gas, and natural resources; private ownership of all other property, but control of it for the public good; abolition of the privately owned Federal Reserve and establishment of a government-owned central bank; “the lifting of crushing taxation from the slender revenues of the laboring class” and substituting for it taxation of the rich; and the guiding value that “the chief concern of government shall be for the poor.”

Huey Long, similarly, made fairly radical proposals, as we can read in his whimsical retrospective account of his First Days in the White House, a book completed shortly before he was shot. A reviewer summarized Long’s post-presidential self-description as follows:

He was the man of action who in rapid succession launched a stupendous program of reclamation and conservation, who planned for scientific treatment of criminals, cheaper transportation and popular control of banking. Higher education for all became fact. Tell every parent, he said to his advisers, “I will send your boy and girl to college.” There was much more, but all was overshadowed by legislation for the redistribution of wealth [by means of confiscatory taxation on the wealthy].

These are hardly ideas that shun class conflict. Nor are they obviously “individualistic.” Insofar as Coughlin and Long’s tens of millions of fans, in the working and middle classes, agreed with these political programs, they certainly can be said to have desired fundamental reforms in American capitalism, reforms that would have ushered in a much more collectivistic and socialistic society. It requires the impressive intellectual acrobatics of liberal historiography to differentiate these messages from a class-based populism and claim they can be largely reduced to an “opposition to centralized authority” or a “resurrection of traditional values.”

There is more truth to the way Eric Leif Davin frames the matter in his article “Blue Collar Democracy: Class War and Political Revolution in Western Pennsylvania, 1932–1937” (2000): “Fundamentally, the political mobilization of the working class in the thirties was a class war for political and economic equality.” It is suspicious, after all, that intellectuals are often so determined to deny that the ideal of socialism—workers’ democratic control of their economic life—has much appeal to working Americans. Why wouldn’t it, inasmuch as people obviously want control over their lives and livelihood? Indeed, Brinkley admits as much when he says that Long, Coughlin, and their followers called for “a society in which the individual retained control of his life and livelihood; in which power resided in visible, accessible institutions; in which wealth was equitably (if not necessarily equally) shared.” The obvious reply to this characterization is that it is little but a watered-down definition of socialism!

If American workers don’t always flock to the banner of socialism or communism, the most plausible explanation, prima facie, isn’t that they are deeply attached to some traditional ideology or are the benighted victims of bourgeois hegemony but simply that they understand it is hopelessly unrealistic, for now, to try to achieve a democratic economy. As Vivek Chibber has recently argued, it is their rationality, not their ideology, that generally keeps working-class Americans from throwing themselves into the profoundly difficult (and frequently criminalized) project of building a nationwide class movement that can overthrow the structures of capitalism.

As historians, rather than endlessly investigating “ideology,” we might do better to, say, follow Noam Chomsky’s practice of foregrounding brute repression and censorship. These factors have overwhelming explanatory value.

As historians, rather than endlessly investigating “ideology,” we might do better to, say, follow Noam Chomsky’s practice of foregrounding brute repression and censorship. These factors have overwhelming explanatory value. This is illustrated by a forgotten incident that occurred in the spring of 1936: CBS invited Earl Browder, head of the U.S. Communist Party, to speak for fifteen minutes (at 10:45 p.m.) on a national radio broadcast, with the understanding that he would be answered the following night by zealous anti-Communist Congressman Hamilton Fish. Browder seized the opportunity to reach a mass audience and expounded the Marxist analysis of capitalism and prescription for a better society.

Reactions to Browder’s talk were revealing: according to both CBS and the Daily Worker, they were almost uniformly positive. CBS immediately received several hundred responses praising Browder’s talk, and the Daily Worker, whose New York address Browder had mentioned on the air, received thousands of letters. The following are representative:

Bricelyn, Minnesota: “Your speech came in fine and it was music to the ears of another unemployed for four years. Please send me full and complete data on your movement and send a few extra copies if you will, as I have some very interested friends—plenty of them eager to join up, as is yours truly.”

Evanston, Illinois: “Just listened to your speech tonight and I think it was the truest talk I ever heard on the radio. Mr. Browder, would it not be a good thing if you would have an opportunity to talk to the people of the U.S.A. at least once a week, for 30 to 60 minutes? Let’s hear from you some more, Mr. Browder.”

Springfield, Pennsylvania: “I listened to your most interesting speech recently on the radio. I would be much pleased to receive your articles on Communism. Although I am an American Legion member I believe you are at least sincere in your teachings.”

Harrold, South Dakota: “Thank you for the fine talk over the air tonight. It was good common sense and we were glad you had a chance to talk over the air and glad to hear someone who had nerve enough to speak against capitalism.”

The editors of the Daily Worker plaintively asked their readers, “Isn’t it time we overhauled our old horse-and-buggy methods of recruiting? While we are recruiting by ones and twos, aren’t we overlooking hundreds?” One can only imagine how many millions of people in far-flung regions would have flocked to the Communist banner had Browder and William Z. Foster been permitted the national radio audience that Coughlin was.

It is true that ruling-class propaganda, constantly flooding the visual, auditory, and print media, can have a major influence on popular attitudes, manipulating the public into “conservative” political positions. But this doesn’t imply the typical Democratic argument that Americans are naturally moderate or centrist, nor does it mean that because they are somehow “steeped in the dominant themes of their nation’s history” they tend to reject left-wing ideas. Indeed, the very fact that it is necessary to deluge the public with overwhelming amounts of propaganda, and to censor and marginalize views and information associated with the political left, is significant. Why would such a massive and everlasting public relations campaign be necessary if the populace didn’t have subversive or “dangerous” values and beliefs in the first place? It is evidently imperative to continuously police people’s behavior and thoughts lest popular resistance overwhelm structures of class and power.

When we consider the findings of polls, we can see why the ruling class devotes such colossal spending to “manufacturing consent.” A few examples may suffice. In 1935, a Fortune magazine poll found that 41 percent of the upper-middle class, 49 percent of the lower-middle class, and 60 percent of the poor thought the government should not allow a man to keep investments worth over $1 million. As late as 1942, 64 percent of people thought it was a good idea to limit annual incomes to $25,000. That same year, another Fortune poll found that almost 30 percent of the nation’s factory workers thought “some form of socialism would be a good thing for the country as a whole,” while 34 percent had open minds about it—which means only 36 percent thought socialism would be “a bad thing.” Given the resources and energy the business class had dedicated to vilifying socialism, these findings are striking.

They may bring to mind more recent findings. Gallup polls have found that 40 percent of Americans (and a majority of Democrats) have a positive view of socialism—which is a remarkable fact, considering that the mass media’s coverage of “socialism” is almost uniformly negative. For a similar reason, the 68 percent approval rating of labor unions is also noteworthy. According to the Pew Research Center, 59 percent of Americans are bothered “a lot” by the feeling that corporations and the wealthy don’t pay their fair share of taxes. Sixty-four percent of people think that protecting the environment should be a top policy priority. As usual, then, the populace is largely to the left of the two major political parties, even after being continually inundated by anti-left propaganda. In fact, a large number of people come very close to believing in communism: according to a poll in 1987, 45 percent of Americans thought the Marxist slogan “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need” is so morally obvious it is enshrined in the Constitution!

But—to return to the 1930s—what about the fact of Roosevelt’s great popularity? He was hardly a revolutionary figure. Given the enormity of the economic crisis, doesn’t his popularity suggest that most Americans are indeed basically “liberal” at heart, congenitally averse to radical social change?

Well, the fact that he was popular doesn’t mean he wouldn’t have been more popular if he had pursued more transformative change. This is suggested, after all, by the stunning success of Coughlin and Long, who in 1934 and 1935 vehemently denounced Roosevelt and the New Deal for their conservatism. Historian Charles Beard observed a “staggering rapidity” in the “disintegration of President Roosevelt’s prestige” in early 1935, while journalist Martha Gellhorn wrote, “it surprises me how radically attitudes can change within four or five months.” Correspondents wrote to Roosevelt that he had “faded out on the masses of hungry, idle people,” had served only the “very rich” and proven to be “no deferent [sic] from any other President.” “Huey Long is the man we thought you were when we voted for you,” a man wrote from Montana. The so-called Second New Deal, which signified a left turn, shored up Roosevelt’s popular support, but it was not nearly as radical as many millions would have liked.

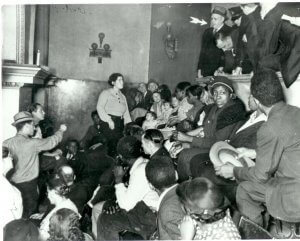

Communists, too, were more popular at the time than we might think in retrospect, despite their self-sabotage by speaking in an alien jargon and consistently praising the Soviet Union’s tyrannical regime. Millions of people passed through the party and its many auxiliary organizations (Unemployed Councils, the Young Communist League, the John Reed Clubs, the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, etc.)—again, in spite of the savage police repression and media censorship to which Communists were subjected. The party even had great success agitating for its remarkable, socialistic Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill between 1930 and 1936, which would have created a social democracy in some respects more expansive than that which any Western European country enacted after the Second World War. Historians have sadly neglected this bill and the nationwide wave of mass support that developed behind it, which led it to be the first federal unemployment insurance bill in U.S. history to be reported favorably out of a congressional committee (the House Labor Committee, in 1935).

In short, a case can be made that, for the sake of both advancing left-wing political goals and highlighting essential historical truths, historians ought to embrace a self-consciously materialistic method that emphasizes above all else the ubiquitously ramifying class struggle. Julie Greene has acutely remarked that even “struggles over environmental justice, human rights, anticolonialism, welfare rights, or women’s reproductive rights” are forms of class struggle. Class is fundamental, as Marx saw, and working people even in the “conservative” U.S. are and have been in many respects very leftist underneath all the ruling-class indoctrination to which we have been subjected. Left intellectuals ought to constantly expose this popular radicalism in public forums and never stop repeating the “reductivist” refrain that the defeat of the left has been a product of ruling-class violence and repression more than anything else. Reductivism has its virtues.