Nat LaCour connected civil rights unionism to teachers’ struggle to build union democracy. A remembrance and evaluation.

The United Teachers of New Orleans (UTNO) defy assumptions about anti-union right-to-work Louisiana. As a small, mostly segregated Black local, in 1966, they held the first teachers strike in the South. In 1974, they won one of the first collective bargaining agreements for teachers in the region. And, by the mid-1980s, with paraprofessionals (school aides) and clerical workers joining their ranks, they became the largest local in Louisiana. Why was UTNO successful when so many other southern teachers unions remained mired in racial strife, unsupported by local communities, and unable to win collective bargaining?

Certainly, part of the answer is the brilliance of union president Nat LaCour, who passed away on October 10th in New Orleans. LaCour won the union presidency in 1971 and went on to lead the local for 27 years, until he was promoted to a position with the national American Federation of Teachers (AFT) in 1998. Though LaCour was a beloved figure, the union’s success came not from his charisma but from his firm grounding in civil rights unionism and his deep commitment to building union democracy.

LaCOUR’S EARLY DAYS

LaCour was born in New Orleans in 1938. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s from Southern University, an HBCU in Baton Rouge, and was attending the school in spring 1960 when Southern students held desegregation sit-ins at department stores and lunch counters in Baton Rouge. Governor Earl K. Long was unsympathetic to the protesters: “I don’t think the colored people of this state have anything fundamentally to complain about,” he told a reporter. “I would suggest those who are not satisfied—like the seven at the lunch counter—return to their native Africa,” and the Southern administration decided to suspend or expel 18 students who were involved in the sit-ins.[1]

LaCour participated in campus protests that emerged in response to the administration’s actions, which became known colloquially as “The Cause.” After earning his degree, he returned to teach in Orleans Parish in fall 1960. However, he could not secure a permanent position because, in an attempt to obstruct federal desegregation orders, the Louisiana state legislature had stripped the Orleans Parish School Board of its authority. He worked as a substitute until he was hired full-time the following semester. As soon as he was hired, LaCour joined the union, then known as AFT Local 527.

The local had a long civil rights history of its own, most famously winning a battle for racial salary equalization in 1943. Throughout the 1960s, Local 527 combined their economic justice demands—primarily for the school board to hold an election for collective bargaining—with explicit calls for racial justice. They demanded desegregation throughout the district, including the hiring of more Black maintenance, custodial and supervisory staff, and aligned themselves with Black students and parents who experienced discrimination when they desegregated formerly white schools. In these tactics, the local positioned itself in the tradition of other civil rights unions, such as the famous Memphis sanitation workers or, closer to home, the International Longshoremen’s Association, who used workplace activism to push for racial equity.

THE COLLECTIVE BARGAINING CAMPAIGN AND THE FORMATION OF UTNO

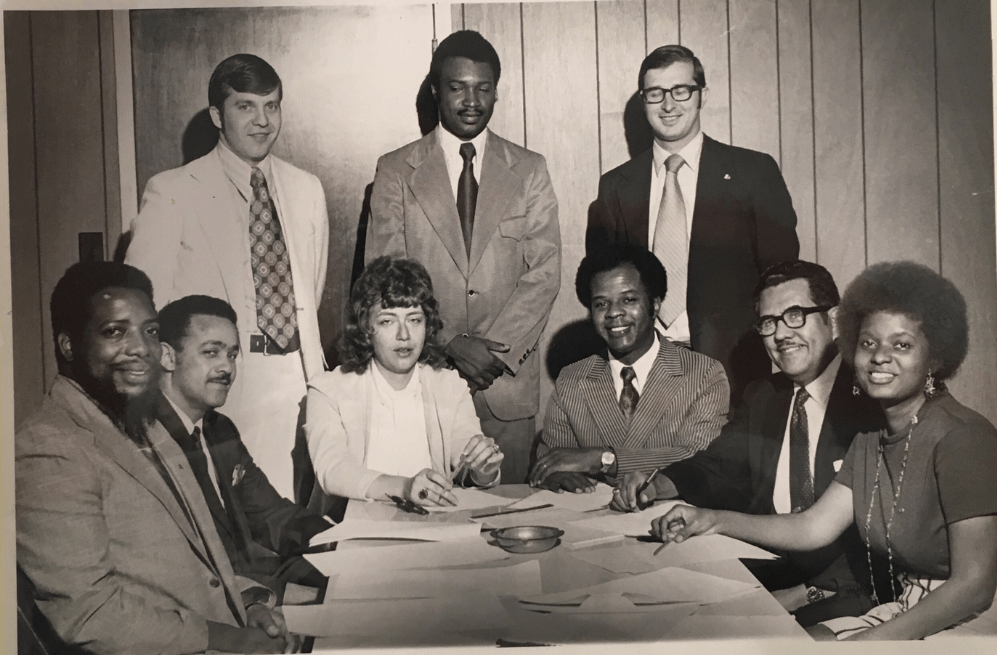

When union membership elected LaCour president in 1971, he had participated in two unsuccessful strikes for collective bargaining and understood that the union needed to build its membership in order to win tangible gains. The following year, threatened with the loss of federal funds, the district administered a top-down program of faculty desegregation intended to create a Black/white balance in every school. Amidst this backdrop, LaCour helped orchestrate a merger between the mostly-white NEA (National Education Association) local and Local 527, which formed UTNO. LaCour continued as president of the new organization, with a white woman from the NEA local, Cheryl Epling, serving as vice president:

“I think UTNO was really the first institution in New Orleans to merge where whites joined a majority Black organization,” explained LaCour. “That had not happened. Integration in the South had been a movement where Blacks integrated into white situations. Blacks went to white churches, Blacks moved into white neighborhoods, Blacks went into white restaurants, but it was never whites moving into a majority Black setting. I think UTNO was the first institution I know where that happened, and that was because people understood that race was not the big factor in our progress, that we needed to be together. So, we didn’t have to love each other, socialize with each other, but we could come together and campaign for our mutual interests. And that’s what happened.”

Now unified, UTNO embarked on a simultaneous community campaign and membership drive. Drawing once more on strategies from the civil rights movement, they worked to engage churches, political groups, and neighborhood associations. Much of this labor was done by member leaders, as UTNO staffer Connie Goodly explains, “Because so many of our teachers and members belong to sororities and fraternities and churches…. Sometimes they would allow us to go into the churches and talk, if you were a member of Greater St. Steven’s Baptist Church, sometimes the reverend would let you stand up and say, ‘This is why we’re doing this.’ If you were a member of Alpha Phi Alpha sorority, you would explain to your sorority girls, this is what we’re gonna do and this is why we’re gonna do it.” By the time they won collective bargaining in 1974, the union had overwhelming community support and represented the vast majority of the teachers in the district.

UNION DEMOCRACY

UTNO’s reliance on member activism, and their extensive leadership development, also drew on the civil rights ideas about effective organizing. Years prior, movement leaders such as Ella Baker and Septima Clark developed theories of power and democracy staunchly opposed to the status quo, pushing for working class leadership, consensus-building, and mass mobilization. Ella Baker and SNCC used non-hierarchical participatory decision making to ensure members were willing to (literally) put their bodies on the line, demonstrating that strong, male, autocratic leadership is not the only “efficient” way to run an organization. [2] Similarly, UTNO developed an internal structure that created numerous pathways to active participation and helped train and uplift women, working class, and Black leaders. The union’s commitment to democratic decision making created an organization that empowered workers and developed the type of transparent and participatory system union members hoped to see in the school board and the city.

LaCour himself promoted democracy and collaboration within the union. Teacher and UTNO staffer Joe DeRose explains how LaCour worked to gain consensus: “Even at executive council meetings, [Nat] made a point of never speaking first. He would lay out the situation, allow everybody who wanted to have their input, he said, ‘Because you never know what ideas are going to come, even from the person who you think is least likely to have a good idea.’” Though these meetings sometimes stretched long into the evenings, LaCour made sure that everyone participated, clearly prioritizing democracy over efficiency.

“What I admired most about [Nat],” reflects UTNO lobbyist Joy Van Buskirk, “was that he took his opposition and embraced them and made them part of his executive board. He never surrounded himself with ‘yes’ people… You know a good leader when you see a leader who understands he or she doesn’t have all the answers to the problems you face. That’s why you have a group surrounding you that will help you when you don’t have those answers. Nat had that group of people. We were all very different. We had different points of view. He had white board members and Black board members… Everything we did emanated through the core of our membership. It wasn’t top down, it was more bottom up. That’s why he was able to build the union he did.”

INSTITUTION BUILDING

Over time, UTNO grew and became more bureaucratic. Yet LaCour remained focused on fostering participatory democracy and creating new paths for leadership development. They developed a state-of-the-art teacher center, which provided resources, training, and mentorship to new and struggling teachers, and hired master teachers to lead classes and serve as mentors. They opened a credit union which allowed many UTNO members to purchase their first cars and houses and created new opportunities for members to serve on the credit union board and educate their peers about banking and finance.

They also built a mighty political machine that focused on electing labor-friendly and progressive candidates and running elaborate Get Out the Vote campaigns, often in partnership with the A. Philip Randolph Institute. Members who served on the Political Action Committee interviewed candidates, joined “Flying Squad” buses to canvas for those the union had endorsed, monitored polls, and even helped develop campaigns. UTNO was able to fight powerful business interests because of their reach, both in New Orleans and throughout the state, and in doing so they built community and member loyalty. According to executive council members, most candidates seeking office in New Orleans solicited UTNO’s endorsement. In one of their more significant political mobilizations, the union played a large role in defeating David Duke, former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, in his 1991 gubernatorial run.

In 1990, the union held another strike, this time to demand raises for low-paid paraprofessionals. Demonstrating their faith in LaCour, picketers chanted: I pledge allegiance to the strike of the United Teachers of New Orleans / and to the cause for which we stand / One union, under Nat, indivisible / with dignity and justice for all.

Members trusted LaCour and he was highly respected in the city and the state. “Nat was always issue oriented, problem-solving oriented,” remembers teacher Mike Stone. “He was the least personally ambitious person. He was always interested in serving the rank and file, improving education, those kind of things.” But members were loyal to the union not because of LaCour’s personality, but because they were deeply involved in union activities and felt like they helped direct its path.

UTNO was not perfect. Critics accused them of protecting bad teachers, fighting too passionately against teacher evaluations, and enforcing arcane contract provisions that did not always prioritize children’s needs. They also endorsed harsh discipline procedures, in the 1990s, that played some role in pushing Black students out of school. By this time, the class divisions in the Black community had grown and most teachers sent their own children to private or parochial schools. Yet through it all, UTNO remained an active, progressive and democratic organization with widespread community support.

HURRICANE KATRINA AND THE MASS DISMISSAL OF EDUCATORS

Seven years after LaCour left for the National, in 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck the city. LaCour’s successor, Brenda Mitchell, had been less committed to the democratic processes at the core of LaCour’s ethos, as she was suspicious of her opposition and questioned their loyalty. Yet she maintained the institutions that LaCour had set up—she herself had been the longtime director of the teacher center—and the union had not seen declines in membership.

Katrina, and the disastrous recovery process, transformed the union’s strengths into liabilities. With their members displaced throughout the country, many without internet or cell phones, there was no possibility of participatory democracy and leadership chains broke down. Just two months after the storm, policymakers fired nearly 7,500 educators, including every UTNO member. “The union is made up of people,” long-time teacher Gwendolyn Adams explains. “The union is not a building, the union is not a name, the union is people. And at that point, when they fired all the teachers, people were displaced all over the country. So there really wasn’t a union, because people were not back home yet, and they took advantage of that.”

New Orleans now is the only major city in the United States composed entirely of publicly funded and privately governed charter schools. There has been an obvious loss of democracy for the citizens of New Orleans, whose elected school board provides only limited oversight. Instead, charter management organizations are governed by appointed boards and hold fragmented meetings across the city. Though teachers are—sometimes—welcome to attend their school’s board meetings, they have little power to influence the board’s decisions or play a role in the appointment of new members.

The New Orleans school privatization saga makes clear that charter schools are, among other things, a tool for union busting. Though it is perhaps strategic for the AFT to tread a careful line without officially opposing charters, the schools, at least in their current incarnation, directly threaten teacher power and the rights of working people. When UTNO was destroyed, policymakers also privatized school custodial and maintenance workers, who had been organized with AFSCME, and bus drivers, who were with the Teamsters. School reformers want charters to be evaluated narrowly on the basis of student test scores and graduation rates, but the city has yet to reckon with the violence that was done to the Black middle class and the Louisiana labor movement.

According to the Education Research Alliance, the percent of Black teachers in New Orleans went from 72% in the 2004-05 school year to 49% in 2013-14. Teachers are also less experienced, less likely to be from Louisiana, and less likely to be certified.[3] The sense of community, democracy, and civil rights history that the union provided are gone.

LESSONS FOR TEACHERS AND ORGANIZERS TODAY

As teachers today look to build power, especially in states traditionally hostile to collective bargaining, they would do well to learn from the example of UTNO and the legacy of Nat LaCour. UTNO achieved success by drawing on four key civil rights tactics:

- Prioritizing disruption: they held four strikes from 1966-1990 as well as other walkouts, pickets, and protests;

- Combining demands for racial and economic justice;

- Developing deep community connections, buy-in, and respect, both on social and on political levels;

- Building a culture that fostered internal participatory democracy and leader development.

“Nat’s attitude to us was that we deserved as much as the teachers in New York deserved. So we fought to get whatever they had in New York,” recalls teacher Grace Lomba.

LaCour’s vision was radical at the time and remains radical today: teachers in the South, Black teachers, deserve the benefits of the United Federation of Teachers, a voice in school decision making, and equitable, well-resourced schools. Most southern schools remain far from this standard, but, as LaCour shows us, organizing has the potential to dramatically change the status quo—especially when it is democratic, collaborative, and prioritizes racial justice.

[1] M’Lean, James. (1960, March 29). Sitdown move is hit by Long. New Orleans Times Picayune. P. 32.

[2] See: Charron, K. M. (2009). Freedom’s teacher: The life of Septima Clark. Univ of North Carolina Press.; Polletta, F. (2012). Freedom is an endless meeting: Democracy in American social movements. University of Chicago Press.; Ransby, B. (2003). Ella Baker and the Black freedom movement: A radical democratic vision. Univ of North Carolina Press;

[3] Barrett, N. and Harris, D. (2015). Significant Changes in the New Orleans Teacher Workforce. Education Research Alliance. https://educationresearchalliancenola.org/files/publications/ERA1506-Policy-Brief-Teacher-Workforce-Cover.pdf