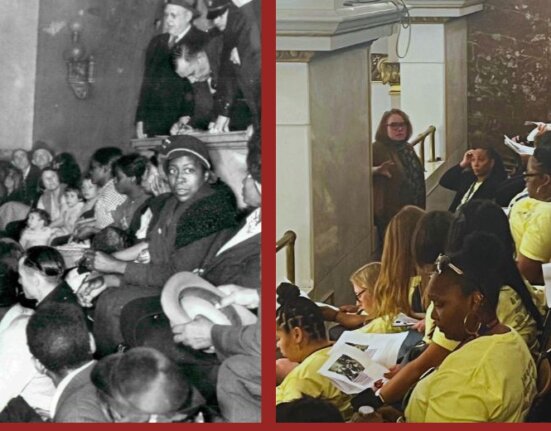

One of the first principles of critical disaster studies is that disasters exist not as time-out-of-time, but as embedded in the times and places that produce them. Because disasters are part of history, not outside of it, they can bring into relief structures of society that were always there. Covid-19, and the economic crisis that surrounds the public health crisis, have revealed much—or rather, made inescapable that which should have been evident before. A crisis in how we pay for health care, such that even in the middle of an unprecedented public health crisis, hospitals furlough workers and cut their pay for fear of going bankrupt. A crisis of home care workers who care for the vulnerable, disabled, and elderly but without their own occupational safety and health protections. A crisis from making food workers, delivery workers, and care workers precarious, underpaid, and often excluded from labor law. A crisis for families forced to rejigger their domestic labor arrangements in the absence of schools. In short, a crisis of care.

This post was originally posted on the University of Illinois Press Blog, where Disaster Citizenship is available as a free download during May 2020.

When a munitions ship exploded in Halifax Harbor the morning of December 6, 1917, it created its own crisis of care. As I describe in Chapter 1 of my book Disaster Citizenship: Survivors, Solidarity, and Power in the Progressive Era, the electronic version of which is a free download this month from the University of Illinois Press, first came the medical crisis, as Haligonians sought treatment for wounds from flying glass, falling timbers, and spreading fires. Hospitals were soon overwhelmed with patients. Many uninjured women, many of them college students, rushed to hospitals as volunteers. While they performed gendered care work, in their own descriptions, they made it clear that what they were doing was new, not simply a familiar extension of the familial care for which patriarchy trained them. In their own descriptions, they repeated emphasized that they were novices and often that they were afraid of or had no experience with sickness. One of them said that when she first arrived at the hospital, her “first impulse was to flee.” And yet by the end, she praised her fellow volunteers: “It was amateur work, but they used judgement and common-sense, which took the place of training.” Indeed, with untrained volunteers outnumbering trained medical workers, they needed to negotiate new social relations. Some chafed at being told what to do by other volunteers; others were glad to find useful work even amid confusion. One medical student described it as “organization without any organization.”

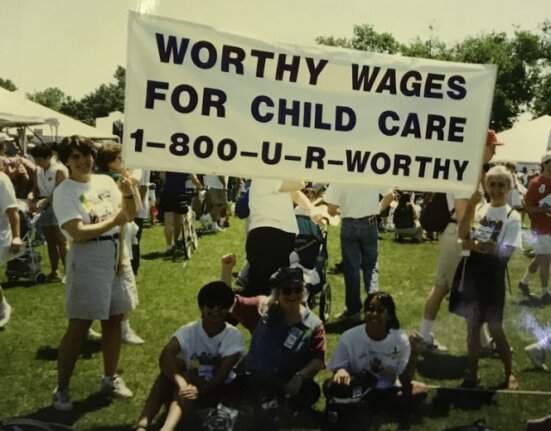

But Halifax’s crisis of care extended beyond medical care. As I detail in Disaster Citizenship’s fourth chapter, working-class Haligonian families relied on complex family economies of paid and unpaid labor. The explosion disrupted that careful balance. The Halifax Relief Commission took over the workman’s compensation program and paid cash to disabled workers or to the survivors of dead workers. But when an unpaid domestic worker—that is, usually, a wife or a daughter—died or was disabled, their families found they had to either have to keep home another, potentially wage-earning family member, or they would have to hire a domestic servant for cash. Either way, women’s domestic labor became financially visible once it could no longer be performed.

To solve this problem, the Relief Commission granted pensions to housewives. In families where husbands earned less than $20 weekly, the policy said, “his wife should be regarded as practically a wage-earner, by reason of the fact that she does all the work of the household and indirectly contributes to the maintenance of the family, and therefore there should be some compensation for that partial disability.” These pensions were small and arbitrary, and many women who should have been eligible were denied them. And yet their very existence shows that in the midst of crisis, some Haligonians, including those in power, were able to see better what had always been there: the crucial importance of care to the functioning of society and the economy.

In our own extended crisis, we too can take the opportunity to see what has long been present: the fundamental inequities that make the most essential of workers also the most vulnerable. What Covid has revealed is that the truly essential work of society is care: care for the sick, care for the young and the old, the care work of food production, the mutual care that allows any of us to function in the world. We are all mutually dependent on networks of mutual care. And yet that work—if it is paid at all—is often ill paid and performed by marginalized workers. Thanks to Covid we can see more clearly the harm caused by the fantasy of the independent individual; when we emerge from this crisis, we must place care at the center of our society.