The attacks on labor these days take many forms. Some are straight-forward and brutally confrontational—the Janus ruling or the state legislation in Iowa and Wisconsin and elsewhere that follow a similar script in their attack on labor’s position of strength in the public sector. Others are somewhat more subtle, masking their intent in a veneer of praise and hand-wringing. Such is the case with the University of Iowa’s announcement (without prior consultation) that it will close the UI’s long-standing Labor Center, because of supposed financial exigencies beyond its control.

First, a little background. The UI Labor Center, like similar institutions at many public universities, has been around for more than 60 years. It was created when labor had considerable strength in the postwar years and when public universities, with strong support from state governments, were expanding their size and mission. The idea that a “public” university should serve a broad public seemed natural, even normal. So, the Labor Center at Iowa did what many labor education programs did, and more. It taught short courses for trade unionists, helped them increase their bargaining skills, learn the basics of labor law, master the intricacies of health and safety legislation, public relations, labor journalism, civic engagement skills, and learn some labor history. It met a real need. Workers responded with enthusiasm, felt empowered, humanized, and bolstered in their work lives and their work as local leaders, whether as shop stewards, union officers, or labor educators in their own local realms of activism.

With changes in the labor force and new organizing strategies, the Labor Center has broadened its mission and moved to document and provide training to low wage and contingent workers, many of them immigrants and people of color, around issues of wage theft, the right to organize and engage in collective action, and their very right to citizenship. In doing so they have opened opportunities for undergraduate internships and faculty research on issues facing these vulnerable workers.

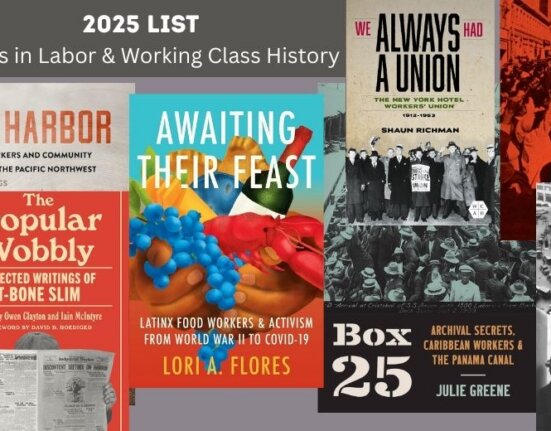

But the UI Labor Center has done more. In support of the ideas of progressive leaders like Jim Wengert, a packinghouse worker, union activist, and eventually President of the AFL-CIO Iowa State Federation, and Mark Smith, a teachers’ union activist, labor educator, and AFL-CIO Iowa State Federation Secretary/Treasurer, they helped craft a pioneering oral history program that was uniquely funded by union members’ per capita dues; this put trained oral historians in the field to collect and process what became an unprecedented collection of 1500 oral histories, ranging in length from 2 to 8 hours. A sampling of those remarkable interviews in a book I edited, Solidarity and Survival: An Oral History of Iowa Labor in the Twentieth Century (U Iowa Press, 1993) has been read by thousands of workers (and their children as UI undergraduates) across the state. (I’ve seen dog-eared and well-worn copies that have been passed from hand to hand on the shop floor.)

Now, a little context for the current attack on the Labor Center. After a deeply-flawed and much-criticized hiring of a new university president, Bruce Harreld, a businessman with no academic credentials, the university has proceeded down a path of draconian budget cutting in line with the Republican-dominated legislature’s mandate to gut the “public” funding of the “public” universities in the state. By raising tuition and recruiting larger numbers of full-paying out-of-state and foreign students, the university has willy-nilly acquiesced to its own “privatization.” While wringing his hands about lower levels of state government funding, Harreld and the administrators around him have talked increasingly about a “generational” change in state higher education, a code word for their fundamental acceptance and even consent to these changes.

This is not surprising. Many of us believed that this was precisely why Harreld was hired—to carry out the Republican mandate to starve the public universities. It is also not surprising that the impact has been applied disproportionately to the humanities and the liberal arts, where a years-long defacto hiring freeze has been effect, and whose disciplines often foster deeper understanding and critical engagement with history and public life. Not surprising as well is the university’s rhetoric about justifying programs in terms of their contribution to the state’s economic development, a rhetoric that has escalated in the current crisis.

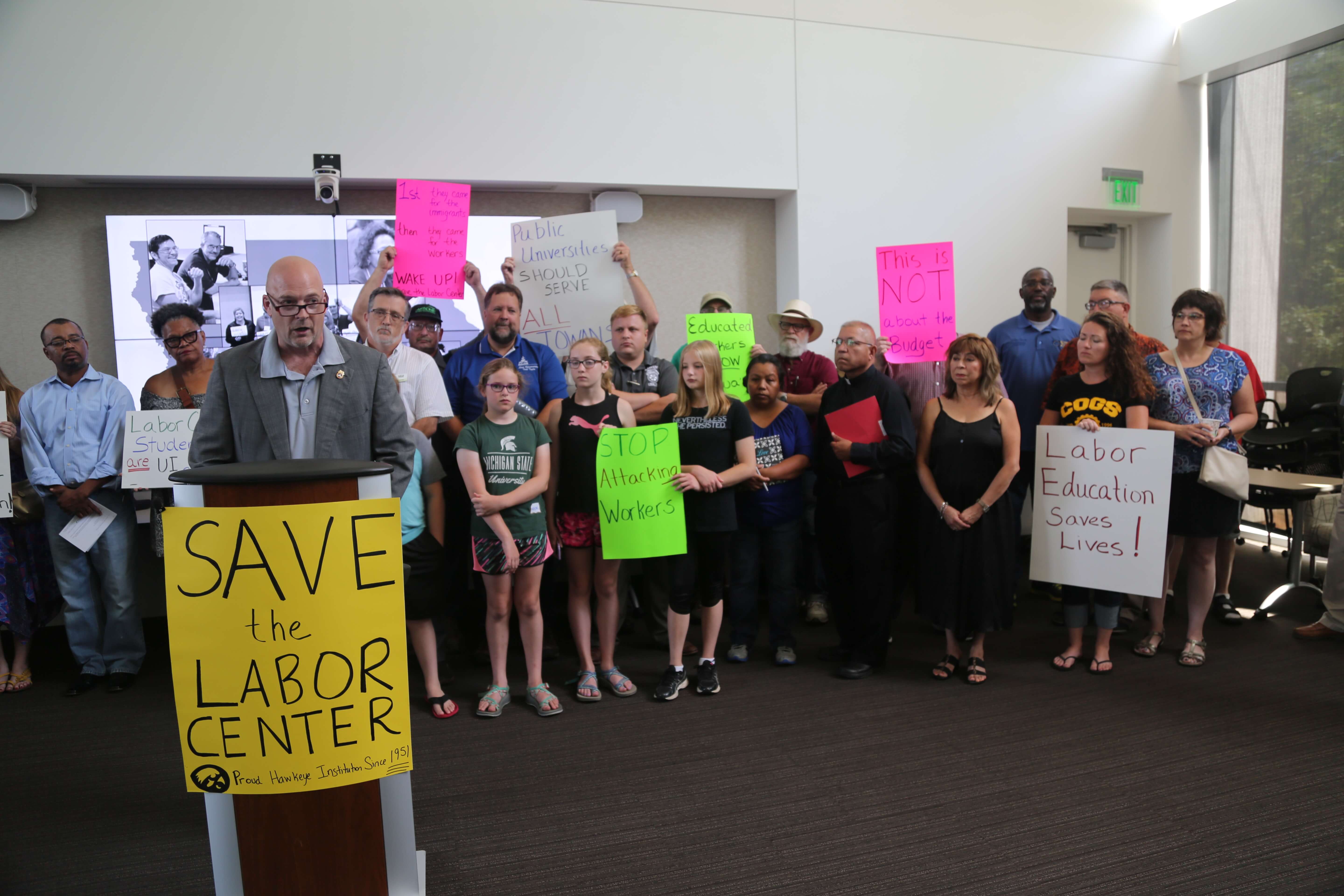

Clearly in the present political climate, any program that serves workers (or their children) becomes a prime target. Having hoped to emasculate the state’s public-sector unions through new draconian legislation in 2017 (but thanks to workers’ commitment to their unions this is not turning out quite the way they hoped), it is only logical that they would move against labor education programs that serve to empower workers with skills and knowledge that strengthen their ability to fight for their rights and negotiate effectively on their own behalf. But, unexpectedly for the university administration the news that the university was summarily closing the Labor Center has brought forth an unprecedented wave of public support for its exemplary work that has university officials back on their heels. The struggle remains very much ongoing and additional support from Iowans and their allies around the country is essential.

LAWCHA members and allies, we need your voice. Please send an e-mail to President Bruce Harreld (bruce-harreld@uiowa.edu); Law School Dean (who supervises the Labor Center) kevin-washburn@uiowa.edu; and let Jennifer Sherer (labor center director and past LAWCHA board member) know about your support: Jennifer-sherer@uiowa.edu.