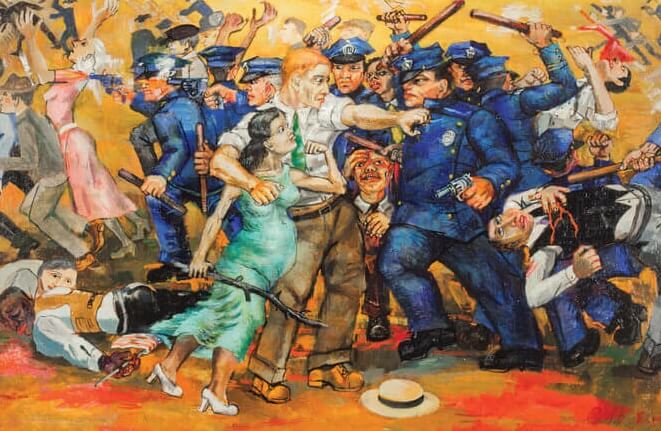

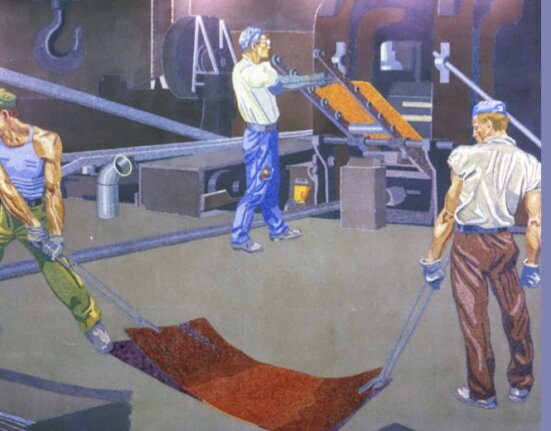

On the afternoon of Memorial Day, 1937, at least 1,500 striking steel workers and their supporters marched across a sun-drenched field in the southern reaches of the City of Chicago, intent on vindicating their right to set up a large picket line the main gate of a plant owned by the Republic Steel Corporation and thereby pressure that company to recognize and bargain with their union. The demonstrators were intercepted by 250 city police who, with little provocation, opened fired on them, killing or mortally wounding ten and injuring dozens of others with gunfire and blows they rained down with night sticks and hatchet handles. This infamous event, known as the Memorial Day Massacre, is only one of many episodes that defined one of the most tragic and widely misunderstood labor conflicts in American history: the Little Steel Strike.

The strike involved over 70,000 workers at nearly thirty mills. It occurred immediately after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Wagner Act, the legislative centerpiece of the Second New Deal, which purported to grant workers the right to strike and picket, to form unions of their own choosing, and to compel employers to bargain with those unions. The Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC), part of the new renegade federation, the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO) seemed poised to break through the anti-union strongholds. At the center of that stronghold was a consortium of powerful steel companies—Little Steel— that were, with the backing of powerful industrial and political interests, intent on defying the Wagner Act, resisting the SWOC’s organizing efforts, and undermining the CIO and blunting the push for industrial unionism.

Practiced in labor repression and well-armed, the Little Steel companies were led by Republic Steel. In the course of the strike, company agents and their allies killed at least sixteen workers and seriously injured several hundred others. Despite the steel workers’ remarkable courage and determination, the companies broke the strike, relying on a combination of repression, political and legal manipulations, and raw economic power to do so. They also effectively fired 8,000 strikers. The drive to organize Little Steel collapsed. The CIO itself was seriously weakened. And in the months and years that followed, the movement for industrial unionism in steel was nearly destroyed.

Many historians fail to recognize that this was no mere temporary setback for labor. The Little Steel Strike was a test of the Wagner Act. It exposed the statute’s flaws, including its failure to deter labor repression and to support mass picketing and other forms of militancy that offered the strikers their only hope of countering employers’ economic and political power. The strike undermined the CIO’s alliance with New Deal liberalism and politicians who claimed to be labor’s friends. The strike’s failure led the CIO and the SWOC to redouble their embrace of a model of unionism that relied on the support of the state, rather than strikes and other forms of direct action, as the primary means of advancing workers’ rights.

In all these ways, the epic struggle at Little Steel that summer was a crucial moment in American labor history. The story of the strike brings to light dysfunctions in the labor law that have burdened the labor movement and the cause of workers’ rights since the 1930s. It exposes both the promise and the limits of labor militancy. And it is also offers a crucial occasion to reflect on labor’s political situation today, including the roots of the labor movement’s fraught relationship with mainstream liberalism and the Democratic Party.

This is the story I tell in The Last Great Strike: Little Steel, the CIO, and the Struggle for Labor Rights in New Deal America, recently published by the University of California (2016).