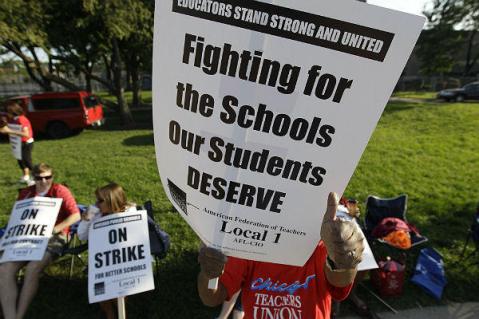

June’s LAWCHA conference was my first. I had an excellent time, presented my work on a successful panel about blue-green alliances, and a chaired a really great panel on the 100th anniversary of the Paterson textile strike of 1913. But the most important panel I attended was on the Chicago Teachers Union struggle. This roundtable, consisting of a broad array of scholars and activists, focused on the CTU’s 2012 strike and victory over Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel’s attempts to gut the teacher union and reduce teachers’ job security through an emphasis on teacher evaluations and other “reforms” that privatize education and undermine teachers actually teaching. Led by president Karen Lewis, the CTU struck in September and forced Emanuel to heel, negotiating a deal with that pleased no one, but was better for teachers that what the mayor wanted. CTU militancy in standing up to Emanuel inspired unionists around the country, leading some to see the union as a potential model of democratic unionism able to maneuver through the difficult waters of the early twenty-first century.

A single panel on such a complex situation allowed for only a relatively brief discussion, but the panelists all provided valuable points. Steven Ashby provided an excellent and useful introduction discussing the important issues at play. Particularly memorable was New York teacher Megan Behrent’s discussion of the struggles of her and other reformers to turn their union into one with the kind of militancy and solidarity the CTU has displayed. Unfortunately, the entrenched leadership of many teachers’ unions, as well as a long history of member apathy and a dispiriting political situation have made it hard to organize around the recent attacks on teacher unions. For many teacher union activists, the CTU remains closer to an aspirational model than something their colleagues are ready to replicate.

The panel’s real highlight was hearing CTU member Becca Bor talk about the struggle she and her fellow teachers face. Bor told great stories of the terrible conditions of the schools that make teaching and learning almost impossible, building the union up at the school level, the joy and strength found when different schools got together. The CTU’s democratic unionism also played a major role in the discussion, particularly the time CTU leadership took to give teachers a chance to read, discuss, and vote on the contract, much to Emanuel’s chagrin who wanted the strike to end immediately. However, Bor stated the CTU struggle was far from over. That preliminary victory has been followed by Emanuel closing fifty Chicago schools and using Teach for America as a union-busting force rather than find positions for some of the laid off teachers. The 2012 strike was a huge win, but really more the first round in a struggle that will last for years.

In thinking about the CTU’s meaning for the labor movement writ large, one panelist briefly mentioned how it might make us rethink labor’s long-standing relationship with the Democratic Party. I tried to follow up on this thought with a question, but no one quite wanted to say (or did say anyway) that in the short term, this might be the biggest lesson we can learn from the struggle. While the labor movement has good reasons to support Democrats, when union-busters like Emanuel win office, I see no reason to worry about embarrassing the national Democratic Party by holding back. Some argued that the CTU should not strike in 2012 because Emanuel’s ties with Obama meant it could embarrass the president in his reelection campaign, potentially helping an anti-union Republican win the presidency. That’s a terrible argument showing labor as its most timid. Ultimately, labor needs to stand for its own principles outside of the party system. This doesn’t mean a return to Gompers-era nonpartisanship, but it does mean picking allies carefully and having a willingness to hurt the Democratic Party if it does not support the needs of labor, whether locally or nationally.

The CTU panel was one of many LAWCHA panels that focused on the present rather than past. This opens up important questions about the relationship between ourselves as historians and current struggles. As labor historians, we really want the CTU to be the harbinger of a turnaround for organized labor. But I think we have to create some critical distance between our work and our hopes that any given workers’ movement will finally be the spark that revives the labor movement. I’ve recently read historians who wrote about contemporary struggles following the WTO protests in Seattle, Occupy Wall Street, and the rebellion against Wisconsin governor Scott Walker. Each of these incidents led historians to predict a resurgence for labor. Unfortunately it hasn’t happened, making some of this work dated mere months after its writing. I have no idea whether the CTU is an isolated case or the beginning of a more militant teachers union movement willing to push back against the bipartisan project of undermining teachers. The panel certainly didn’t help me decide this question. But it did provide valuable context and first-hand accounts of the struggle that we can hope becomes a model for other public sector unions across the country.

Given the two months that has passed since the original panel, if anyone has anything they would like to add about the panel, I urge you to do so in comments.

4 Comments

Comments are closed.