Produced in 1958 by the National Right To Work Committee, the 26-minute film …And Women Must Weep tells the story of a small, working-class Indiana town in crisis, a community that was brought nearly to ruin by an aggressive, brutish union and needless labor unrest. It is a classic cultural text that deserves our notice for its role in reflecting and constructing anti-union culture.

Presented in vivid color, many employers of the 1960s, 1970s, and even the early 1980s, showed And Women Shall Weep in workplaces to unorganized workers – hoping to dissuade them from supporting or joining the labor movement. Based on events surrounding the 1956-1957 International Association of Machinists (IAM) strike at the Potter-Brumfeld Company in Princeton, Indiana, this industrial propaganda film editorializes that organized labor’s brutality, foreignness, and authoritarianism justified states’ anti-union measures and validated industrial workers’ skepticism toward the labor movement.

…And Women Must Weep remains a historically significant and rich (though perhaps forgotten) cultural text of the 1950s and 1960s. For labor and working-class historians, it serves as a helpful and accessible primary source on anti-union culture in the United States, post-Taft-Hartley Act; and works as an excellent undergraduate teaching tool for many of the arguments employers used to de-legitimize organized labor in the post-World War II period.

The film begins at a Protestant church in the southern Indiana town of Princeton, the home of an unnamed industrial firm that employs a large number of the town’s residents. Along with his spouse Winnie, whose voice narrates the film, Reverend Ed Greenfield greets the parishioners who all work at the local plant. It was supposed to be a quiet, typical Sunday: attendance at church, helping neighbors with household projects, time spent with family. However, insidious trouble lurks in the form of a surprise union meeting that had been called by the local’s leader, Halley Thompson. As worker Clark Jones arrives at the meeting, he watches and listens as Halley looms over the assembled union members, haranguing them about the company’s alleged plan to get rid of him. (Halley had skipped some shifts at work and thus violated the union’s contract with the company.) “The only thing they [management] understand is a strike,” Halley shouts at the union members. When the workers tried to question Halley about what happened, why management had fired him, the union boss shouts that “it don’t mean a thing.” Halley forces the assembled workers to authorize a strike.

The sudden strike proceeds to divide Princeton into two camps: the strikers, whose ranks are augmented by mysterious outsiders who sow violence and discord in the town; and the “splinters,” those residents of the town who are (rightly) suspicious of the union and want to see the strike brought to a conclusion immediately (in order to guarantee the townspeople access to the jobs upon which their whole lives depend). “On the side of law and order,” the splinters try to cross the picket line, only to be met with violence and intimidation by “strong-arm toughs.” Moreover, mysterious strangers “from out of state” begin to harass and threaten the locals who oppose the strike: they make threatening phone calls to splinters’ homes; slash car seats and pour paint on cars; bomb a worker’s home; and fire gunshots into a couple’s trailer, seriously wounding their infant child.

Only then, after a baby had nearly been killed, did the strikers in the Princeton begin to realize the foolish trust they had placed with the underhanded “union bosses” and “goons” who had spread division and hate in the town. But thanks to the principled efforts of local minister Ed Greenfield and his wise allies in the “splinter” cause, the state of Indiana passes its “right-to-work” law that would now protect workers’ right to say no to the labor movement’s interference in their lives. Simultaneously, “almost through some miracle,” the injured infant recovers.

…And Women Must Weep is bookended by first-hand testimonials intended to lend authenticity to the film.The National Right To Work Committee also made available a collection of fabricated documents to accompany the film. First, Anne Stewart, who is a former union official (a “vice president of the union staff” at the IAM local), speaks to the audience, and she twice claims that the film is “absolutely true.” She concedes the argument that craft unions are valid institutions since they once accomplished so much for American workers, but admits that she opposes the “corrupt” practices which now overshadow the labor movement: such as unions’ use of workers’ dues to support unpopular candidates and causes; the closed shop; the calling of “cruel” and unwanted strikes; and the rise to power of dishonest and aggressive leaders. Second, the actress who plays Winnie Greenfield introduces the real minister’s wife, who claims the residents of Princeton, Indiana, came “face to face with tyranny” during the Potter-Brumfeld strike. “Freedom is everybody’s business,” she concludes, cautioning that “your town might be next” to confront industrial unions and their destructive strikes.

As the above synopsis suggests, there are three principal arguments the film emphasizes: (1) The labor movement is a belligerent institution, populated by ill-intentioned leaders and a bullied, quiescent rank-and-file membership; (2) organized labor readily uses violence to intimidate its own members and achieve its nefarious goals; and (3) the labor movement’s use of terror is a fundamental and real threat to the domestic tranquility of the 1950s home, as labor’s inclination toward violence dangerously bleeds over into workers’ personal lives.

First, the film uses the brief appearance of local union leader Halley Thompson to illustrate its main argument that unions are combative and ill-intentioned institutions. At the Sunday union meeting that begins the strike, the imposing Halley lords over the rank-and-file, shouting about how he had been mistreated by the company and that the only course of action was to strike. Despite workers’ misgivings, Halley and his committee of leaders in the union “ramrodded a wildcat” and “workers never got a chance to open their mouths.” The film emphasizes that rank-and-file union members too often accept the unjust demands of their slapdash leaders, thereby allowing needless strikes to occur. As the strike begins, rank-and-file workers such as Clark Jones shake their heads and resign themselves to the conclusion that Halley must “know what he is doing.”

Second, this union militancy rests upon needless violence and sinister intimidation. As Winnie Greenfield’s narration claims, “Violence – dirty and utter – was the goon’s method of subduing Princeton.” The onset of the strike, according to the film, brought with it intense violence: overturned cars at the plant; vandalized property; “psychological warfare” in the form of harassing phone calls; and two cases of attempted murder. This violence results not only from the actions of the local union, but from the actions of shadowy outsiders – dangerous allies of the union’s wicked cause — who were “strangers” to Princeton. …And Women Must Weep very powerfully envisages for audiences the equation of violence with the politics of the labor movement.

Third, the film creates a heightened sense of urgency for the viewer by framing labor’s violence within the spaces of the community and the family. The labor movement’s strike violence brings “hate, despair, and fear” to the families of Princeton; it even takes casualties. “Oh Lord, protect the children against this evil,” prays Winnie Greenfield as the strike’s violence stalked her family. “Home was to become a barricade against the menace outside,” but nothing could protect Princeton’s families from the violence of the strike. Even the most innocent, such as the Cartwrights’ newborn daughter, were vulnerable to the danger. How could good people ever support an institution that causes such wanton violence and threatens wholesome communities and families? The film argues that organized labor works against the sensibilities of good families and communities, as its leaders pursued strikes that were brazenly violent and so damaging to families’ safety.

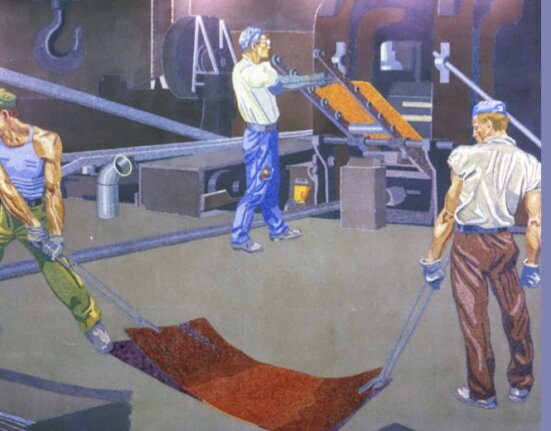

Much of …And Women Must Weep, however, is completely untrue – an artful cinematic distortion of the facts. In 1961, the International Association of Machinists released a brief film of their own, the 18-minute Anatomy of a Lie, which refutes many of the claims made in the National Right to Work Committee’s story. Working systematically on a point-by-point basis, the producers of Anatomy of a Lie visited the actual town of Princeton in order to discuss more fully and accurately the circumstances surrounding the strike at the Potter Brumfeld Company. For example, the IAM’s filmmakers found that the majority of the workers who went on strike were women. (…And Women Must Weep implies that the workers at Potter Brumfeld and the strikers were all “big,” “burly” men, suggesting an untrue gender division of labor at the plant among the men who “must work,” as the lines of Charles Kingsley’s 1851 poem states, and the women who remain at home to “weep” for them.) (1) In addition, the real leader of the IAM local was a sight-impaired woman named Ruth Monroe; she did, in fact, lose her job. (Potter-Brumfeld’s management fired her when she missed several days of work in order to visit an eye specialist in St. Louis, Missouri.) The strike itself resulted not from the actions of a pushy male union leader, but from many working women’s frustrations with new company management that had turned the firm upside down, introducing many unpopular work rules and intrusive time studies of work processes. Ruth Monroe claimed she told the mostly women workers not to strike, but a majority of the workers at a public meeting voted to walk off the job. Anatomy of a Lie also disputes the National Right to Work Committee’s claim about the baby that had been supposedly wounded by a union sniper’s bullets. The film explains that while an infant had been accidentally shot in Princeton, there was no known evidence that actually connected the incident to the strike.

Despite the film’s severely flawed treatment of the Potter-Brumfeld strike, employers regularly screened …And Women Must Weep for captive audiences of workers, as Anatomy of a Lie pointed out. For example, several National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) cases of the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s referenced the power of film to influence workers’ opinions before union elections, citing …And Women Must Weep as a frequent and potent anti-union showcase. (2) While the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 guaranteed employers’ free speech rights during unionization campaigns, the NLRB nonetheless believed that propaganda films gave too much weight to management’s point of view: that workers should reject unions in representation elections. Throughout the 1960s and into the early 1970s, the Board ruled that the showing of the film constituted a violation of the National Labor Relations Act (the Wagner Act), citing in particular “the conditions under which it had been exhibited”: especially employers’ “captive-audience showing[s]” during those periods that preceded union representation elections.(3) Later decisions, however, revealed that the NLRB would reverse course, finding that the mere screening of propaganda films such as …And Women Must Weep did not interfere with the National Labor Relations Act’s promise to workers of the right to organize unions and choose representatives for the purpose of collective bargaining. The Board members concluded that the National Right To Work Committee’s film, on its own, was not “so overpowering as to justify, per se, an election set-aside.”(4)

While the National Labor Relations Board became ambivalent about the cultural power of film in the workplace over the course of the 1970s,(5) today’s labor and working-class historians (and their students) will surely be very impressed as they reconsider …And Women Must Weep. The enduring quality of the film’s production (and its accessibility), as well as its richly told political arguments, make it possible for students and scholars to consider the role of film in shaping post-World War II anti-union culture in the workplace and beyond.

- For more information on the gender division of labor implied in the lines of the poem, see “The ‘Three Fishers’ Song,” New York Times, 24 January 1904, 5.

- Joseph A. Pilcher and H. Gordon Fitch, “And Women Must Weep: The NLRB As Film Critic,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 28:3 (April 1975): esp. 395, 399. On the showing of the film as late as the 1980s, see Purolator Products, Inc. & United Paperworkers International Union, AFL-CIO, 18 May 1984, 270 NLRB 87, p. 709, https://www.nlrb.gov/cases-decisions/board-decisions

- Pilcher and Fitch, “And Women Must Weep,” 399.

- Pilcher and Fitch, “And Women Must Weep,” 404.

- Pilcher and Fitch “And Women Must Weep,” 404-405.

Acknowledgements

For their comments on this paper, I thank Mihaela Wood and Mary Jane O’Rourke; I also thank Jared Ritchey for his help with the still footage images that accompany this paper.