In This Issue

Editor’s Introduction

- Leon Fink, “Editor’s Introduction“

The Common Verse

- Jason Allen, “Where All His Time Was Spent“

LAWCHA Watch

- Julie Greene, “Building the Center for Global Migration Studies“

Up for Debate

- Eric Arnesen,”Introduction“

- Suzi Weissman, “One Hundred Years since October“

- Tony Michels, “The Russian Revolution and the American Left: A Long View from the Twenty-First Century“

- John D. French and Alexandre Fortes, “Jacobins, Bolsheviks, and the Dream of Revolution: October 1917 in the Trajectory of a Brazilian Metalworker of African Descent“

Articles

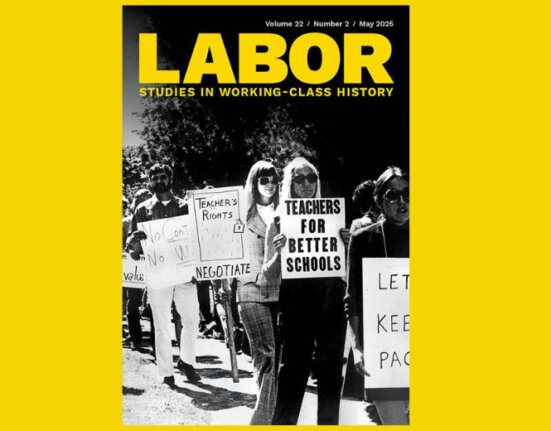

- Diana D’Amico,”An Uneasy Union: Women Teachers, Organized Labor, and the Contested Ideology of Profession during the Progressive Era”

During the early years of the Progressive Era, women teachers in urban centers across the United States bound their fight for equal pay and voice within the schools to a broader social and political activism, each propelled by an image of the professional woman: independent and autonomous in and outside the schools. Without the right to vote, these women turned cautiously toward organized labor to achieve their goals. However, the union between labor associations and organized teachers was troubled from the start and complicated by gender and class. As this article chronicles, affiliation with labor brought increased power and visibility to teachers nationwide but also thwarted the aspirations of early teachers as it severed the connection between teachers’ labor organizations and women’s political activism.

- Janine Giordano Drake, “War for the Soul of the Christian Nation: Christian Socialists versus the Federal Council of Churches, 1901–1912”

Social Gospel ministers fought bitterly with labor leaders over who was better suited to lead the working classes. Christian Socialists upheld a radical Christ who defended unions. They defined a Christian republic through its cooperative ownership and management of industry. The Federal Council of Churches, and specifically the ministry of Rev. Charles Stelzle, identified this working-class Christianity as misguided. Stelzle upheld a politically neutral Christ and a network of American churches that refused to take sides in debates over the ownership of industries. Stelzle’s work within the Men and Religion Forward Movement of 1912 was not simply aimed at organizing by the AFL and neutralizing the appeal of socialism. Rather, through this movement and those that followed, Stelzle sought to undermine the appeal of radical, working-class churches and replace the moral authority of Christian workers with that of Protestant ministers and social services experts.