Many of the more than 150 million migrant workers around the world endure abusive conditions—and one of the most exploitative phases of transnational labor migration takes place before migrants even leave their home country: recruitment for work abroad.

Forced to take on debt to pay the exorbitant fees labor brokers charge to secure a job, migrant workers often cannot repay it even after working for years. Trapped in debt bondage, a situation further exacerbated when workers’ visas are tied to employers and employers confiscate workers’ passports, they have no means of escape when employers abuse them or withhold wages.

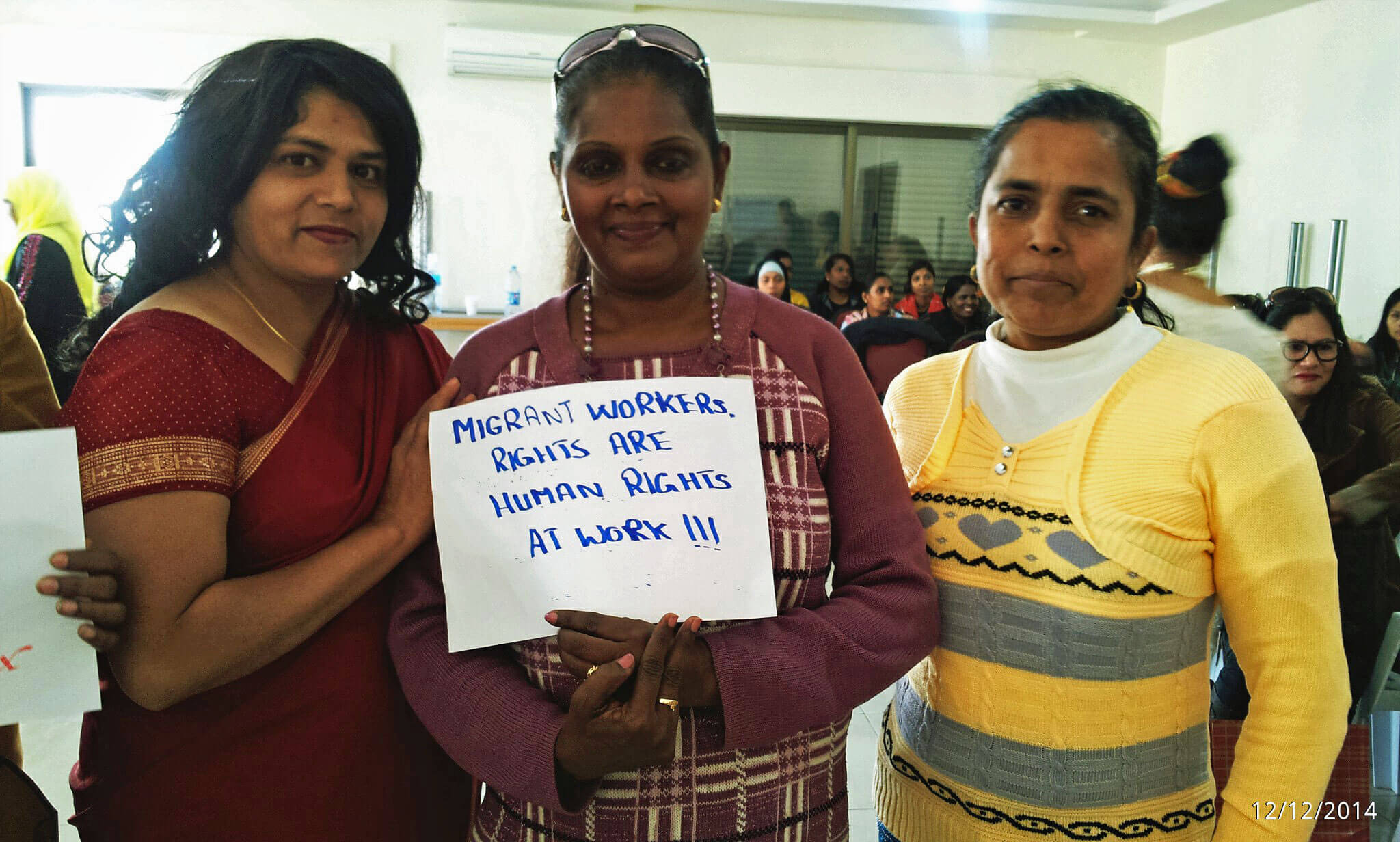

“Labor recruitment fees can lead to debt bondage and should be eliminated,” says Sonia Mistry, senior program officer for Asia at the Solidarity Center, an international worker rights organization. Mistry took part in Civil Society Days, a series of panels and events by nongovernmental organizations leading up to the December 10–12 Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD) meeting. Participants in Civil Society Days presented recommendations to representatives of the more than 100 governments meeting at the annual GFMD conference.

GFMD events, which took place this year in Bangladesh, coincided with Human Rights Day December 10. Commemorated annually, Human Rights Day marks the date in 1948 when the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which includes the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

‘Multinationals Must Hold suppliers Accountable for Forced Labor’

Mistry, who spoke on the Civil Society Days panel, “Protecting and Empowering Migrant Workers in all Global Supply Chains,” says multinational corporations have not done enough to prove to consumers that their supply chains are not tainted with forced labor.

“Multinational corporations need to exert their significant power as buyers to hold suppliers accountable for supply chains free of forced labor,” she says. Companies argue that it is too difficult or expensive to completely map their supply chains.

The recruitment and placement industry is a $464.3 billion-a-year industry.

During the recruitment process, it is routine for recruiters and their agents to make false promises about the jobs on offer, charge would-be migrants fees that exceed their annual income and offer loans at usurious rates, demanding property deeds as collateral.

Mistry and co-panelist Anup Srivastava from the Building and Wood Workers International (BWI) say promoting the rights of migrant workers in supply chains requires a multifaceted approach that can be undertaken even in difficult environments—“so there is no space for ‘it’s too hard’ excuses by employers or governments,” Mistry says.

At the panel, Mistry will recommended:

- All workers have equal access to internationally recognized labor standards, regardless of where they are.

- Workers—who are the best workplace monitors—have the freedom of association rights they are due and are protected to raise and help address workplace safety, health, legal and rights violations. “At all points in the supply chain, unions serve as key partners in promoting decent work and addressing some of the most egregious rights violations, including child labor, forced labor and gender-based violence,” says Mistry. “No auditing system or third-party verification scheme can replace the role of unions.”

- Binding and enforceable agreements be struck to enforce and protect worker rights. These can take many forms, from an International Labor Organization (ILO) standard to a collective bargaining agreement.

Unions Call on GFMD to Take Action to Protect Migrant Worker Rights

Participants at the GFMD’s ninth meeting considered how member states can design a “Global Compact” to govern the mobility of migrant workers and the possible commitments by stakeholders to create a comprehensive global framework and follow-up mechanism. The Solidarity Center, along with the Council of Global Unions (CGU) and the AFL-CIO, is calling for recognition in the Global Compact negotiations of the “vital role of the ILO, founded on a mandate of social, justice, peace and democracy.”

As noted by the CGU, the “ILO has important standards related to labor migration and a robust system to supervise those instruments. It is also the institutional protector of other workers’ rights that also apply to migrant workers, such as trade union rights (including freedom of association and collective bargaining), forced labor (including trafficking) and child labor, occupational health and safety protection, social security and many others.”

Civil society groups are urging the GFMD to take action to protect migrant workers’ rights by fulfilling the portion of the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 8) that calls for taking immediate measures to eradicate forced labor, end modern slavery and human trafficking, protect labor rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers.

The GFMD is a non-binding and government-led process open to United Nations member states and observers “to advance understanding and cooperation on the mutually reinforcing relationship between migration and development and to foster practical and action-oriented outcomes.”

Unions and other civil society organizations have been advocating for a stronger role for civil society in the GFMD.

A version of this article originally appeared at the Solidarity Center website.