Six weeks following the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri Emerson Electric Chairman and CEO, Michael Farr, unveiled the corporation’s $1.5 million “Forward Program,” a multifaceted five year education and employment package to support “renewed community enrichment and development in Ferguson and the North County area.” A response to the continuing civil protest and unrest following Brown’s death, Farr’s announcement was received with applause by civic leaders, corporate heads and the media while eliciting “Don’t Hold Your Breath” skepticism from the protestors in Ferguson.

When measured against the contrasting realities of Ferguson and the location of Emerson’s world headquarters (about a mile from where Brown was shot) the socio-economic disparity could not be greater. Since 1970 the racial composition of the city has altered radically from 99% White and 1% African American to 31% White and 65% Black in a population of 21,203. Yet all of the elected officials are White as are all but one of the police officers in the city. Young Black males are routinely stopped, searched, arrested, fined and sometimes jailed, mostly for misdemeanors or other minor offenses. The unemployment rate in Ferguson lingers at 12% (6.7% for Whites but 19% for Blacks) and the poverty level stands at 18% (25% for Blacks; 11% for Whites). (1)

A global manufacturing and technology corporation with 150 of its 200 industrial sites located abroad, Emerson has been located in Ferguson for seventy years, first as a major manufacturing plant, then as the national and international headquarters of the firm. Ranked number 121 in Fortune Magazine’s list of 500 companies, 1300 are employed at the Ferguson headquarters. The corporation has a total of 32,000 workers in the United States but nearly 100,000 at plants around the world. (2)

The company’s history is a stunning example of St. Louis’s reach for empire and the paradox of imperial vision in the name of worker and community welfare. Founded in 1890, Emerson had in fact a troubled and conflicted labor-management relationship for much of its history. It had vigorously combated unions during the early years of its existence. During the early New Deal, it ignored Section 7A of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 and refused to recognize or negotiate with the United Electrical Workers (UE) under the terms of the 1935 Wagner National Labor Relations Act.

But well- disciplined and nearly 100 percent organized, Emerson workers retaliated with a sit-down strike lasting fifty-three days, the second longest occupation of a factory in American history. The hard fought strike ended with a union victory in May 1937.

Emerson then brought Stuart Symington, a rising corporate leader, to St. Louis in 1938, to revamp company operations and to streamline Emerson’s management infrastructure and labor relations.

A New Deal supporter, Symington endorsed the Wagner Act, accepted union representation, agreed with minimum wage-maximum hour legislation, favored unemployment compensation and approved the new social security act. He was one of several industrialists and financiers casting themselves as “reform” capitalists who accepted parts of the New Deal political agenda and vigorously backed and participated in Franklin Roosevelt’s international economic foreign policy and the administration’s national defense program.

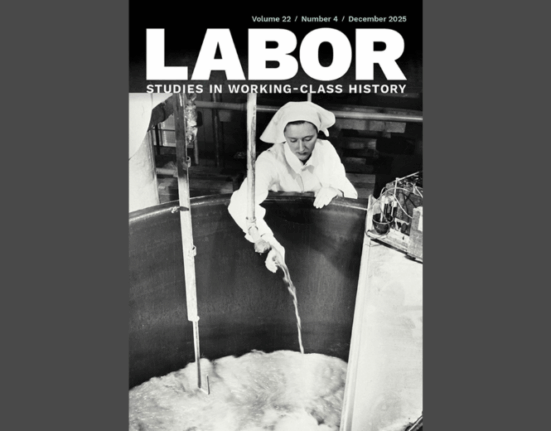

Under Symington’s direction, Emerson built a new state-of-the-art manufacturing facility in Ferguson which opened in 1940. Well-connected in Washington through James Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy, Symington signed on to War Department defense contract offers. Within months, Emerson converted the Ferguson factory to military production. By early 1941 Emerson was fully engaged in the nation’s armaments build-up. As the country’s largest producer of airplane gun turrets, among its defense output, Emerson expanded “from a regional electrical manufacturer into one of the country’s industrial giants.” (3)

During the Second World War, the company’s workforce grew from 1500 in 1941 to over 12,000 employees by 1945. Emerson was among the largest one hundred firms in the country receiving defense contracts. Its trajectory illustrated the dynamics of the developing symbiotic relationship between corporate capital, labor production and the national security state. Stuart Symington transitioned from his corporate defense industry position in St. Louis to become the first Secretary of the Air Force under the National Security Act of 1947 in Washington as a member of President Harry Truman’s foreign policy establishment during the early years of the Cold War. As a consequence of Symington’s position, Emerson was assured of competitive bidding for lucrative defense contracts.

The Cold War also influenced the company’s labor policies and increasing international profile. Emerson adopted a more confrontational approach to UE, exploiting the security and anti-radical provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act, enacted in 1947, and it collaborated with anti-communist, conservative union members to purge UE’s ranks of communist and leftist sympathizers. The company ultimately recognized a rival organization, IUE, in 1949.

As Rosemary Feurer has recounted, Emerson manipulated the division in labor’s ranks to weaken the union’s bargaining power in contract negotiations. It also diminished the union’s presence in the corporation by establishing branch operations outside of St. Louis, in states where “a non-union environment” prevailed. Emerson also greatly enhanced its presence overseas. By 1990 the firm made and sold 25% of its goods outside the United States and in 2007 more than half of its revenues were generated abroad. Emerson had become a multinational corporation. Charles F. Knight, the company’s CEO from 1973 to 2000 was committed to the geographical decentralization of Emerson’s production and weak or non-existent unions in the company’s operations. The company was among the firms moving its corporate production facilities out of the St. Louis region in the last decades of the Twentieth Century. In 1997 Emerson shut down the last of its manufacturing plants in the city and county while retaining its international headquarters in Ferguson. (4)

Today, the corporation’s revenues total nearly $25 billion. Asia is the most lucrative foreign market for sales, production and investments. “Operationally,” David Farr recently reported to Emerson’s stockholders, “we closed 2014 with a strong finish, as profitability earnings growth and cash generation met or exceeded our targets communicated at the start of the year.”

The irony of Emerson’s proximity to Ferguson’s social and economic crises was captured by St. Louis Post Dispatch columnist Kevin Horrigan. His piece, “Two Worlds, A Mile Apart: Ferguson’s Global Giant and Those Left Behind,” was published between the protests which followed Michael Brown’s death and David Farr’s announcement. Horrigan recounted in some detail Emerson’s national and international prominence, its fifty-seven consecutive years of dividend payment increases, its enormous corporate success and the company’s vaunted charitable reputation. Horrigan ended the article with an insipid suggestion that Emerson “could do more” to “reach out to its neighbors left behind by the globalization, automation and computerization that has enriched its shareholders and executives.”

Emerson’s overture, however, may be too little and most certainly way too late. The intense poverty in sections of Ferguson is not separate from Emerson’s fortunes, but a part of the same story.

(1) United States Census Bureau, 2010; Constantine Von Hoffman, CBS Money Watch, “Hit by Poverty, Ferguson Reflects the New Suburbs,” August 19, 20114; Teresa Wiltz, “Poverty is Rapidly Increasing in Suburbs Like Ferguson,” The Huffington Post, August 27,2014. .

(3) James Olson, Stuart Symington: A Life (Columbia: University oif Missouri Press, 2003), pp. 42-23.

(4) Rosemary Feurer, Radical Unionism in the Midwest, 1900-1950 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006), pp.231-232. David Dyer and Jeffrey Cruikshank, Emerson Electric: A Century of Manufacturing, 1890-1990 (St. Louis: Emerson Electric Co., 1990), pp. 1; 28-37; “Emerson Electric, 1999,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, November 3, 1999, pp. 1C-2C. “Emerson Reports Full Year and Fourth Quarter Results.”