In honor of its centennial the Department of Labor began posting a list of “Books that Shaped Work in America”. What does it say about the value the Department of Labor places on labor history when it doesn’t even ask labor historians for input for such a list? As far as I can tell, they list no labor historian on their list of “notable contributors.” Such a list will, of course, vary depending on the specific interests of the compilers, but this one includes titles that have nothing to do with labor, including Madeline Albright’s rationalizations for U.S. military actions in recent history. Or the pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps fairy tales of Horatio Alger’s Mark the Match Boy, the oddly selected third in his rags-to-riches Ragged Dick series.

Three nineteenth century labor titles of immense importance are particularly conspicuous by their absence from this list, especially given that they had far more influence on workers and public opinion about the role of work in American life than most of the other books in the list, as measured by numbers of books sold, effect on public discourse, and long term influence on the direction of the labor movement.

Written by a working printer, Henry George’s Progress and Poverty (1879) offered, as its subtitle suggested “An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth.” Resurrecting old land reform social criticisms, George argued that inequalities would foster even greater inequalities. George’s brilliant explanation of how “poverty” paradoxically grew from “progress” under the existing social and economic inequalities sparked a serious labor party movement, not only in New York where George ran for mayor, but in a number of cities across the country. Moreover, it became incredibly widely-read, influencing the course of labor history throughout the English-speaking world. Nothing over the subsequent generations has made George’s critique anything but more relevant, which makes the absence of his book all the more peculiar–or it may just explain its absence. Most of the other books on the list don’t make such inquiries, but assume that the system is natural, just needing a few tweaks here and there.

Less widely read, but clearly of deep significance was Timothy Thomas Fortune’s Black and White: Land, Labor, and Politics in the South (1884). The son of a black political leader in Reconstruction Florida, Fortune came north as the prospects of black liberation faded. His book rooted the failure of the country to assure justice for African Americans in the obvious unwillingness to disrupt the relations of power and property in the South–or acknowledging that government had the right to do so anywhere in the country. The National Afro-American League, which Fortune had launched in upstate New York during 1890, reorganized into the National Afro-American Council in 1898, laying the foundations for the later Niagra movement and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Fortune’s emphasis on the socio-economic foundations of race remains a terribly useful.

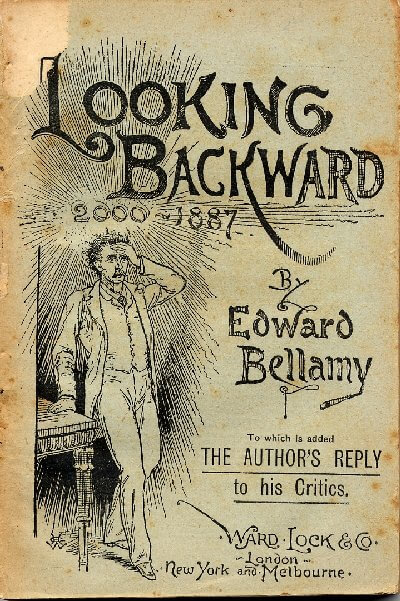

Last, but not least, Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward: 2000-1887 (1888) offered a fictional account of the journey of Julian West from the America of Haymarket Square into an enlightened, genuinely democratic civilization.The novel galvanized middle class concerns about the anti-republican and undemocratic implications of class inequalities. It inspired not only a number of publications, but also the formation of small but influential Nationalist Clubs across town and country in every part of the nation. These, in turn, exercised some influence in the Populist Party, and helped detonate what became the Socialist Party at the close of the century. Bellamy’s concerns turned not only on the unethical nature of capitalism but its ultimate irrationality. His cousin and cothinker, Francis Julius Bellamy wrote “The Pledge of Allegiance,” that remarkable declaration of anticapitalist values to which “under God” was added in the Cold War and has since become, rather bizarrely a designated mantra of those for whom capitalism can do no wrong.

The absence of the classic bestsellers by George and Bellamy–and Fortune’s vital insight into the association of landlessness and racism–tells us nothing little about the importance of those titles, while it reveals much about very much about the process of compiling the list. Perfectly legitimate, widely shared criticisms of work, class and capitalism in America are invisible. Their absence hardly matters, while their presence would be disconcerting. Like great-grandma showing up for the holidays and reminiscing about the Rosenbergs or Gene Debs.

Very disconcerting.

9 Comments

Comments are closed.