The Plenary session of the New York conference of LAWCHA featured an impressive panel of speakers, ticking off a succession of depressing observations about the state of the labor movement, and suggesting some issues and ideas for improving it. We heard little discussion as to why AFL-CIO officialdom has failed to take up any of the good ideas and issues. Nor did we hear any reason to think that they would. Much of the subsequent discussion seems to have continued along these lines.

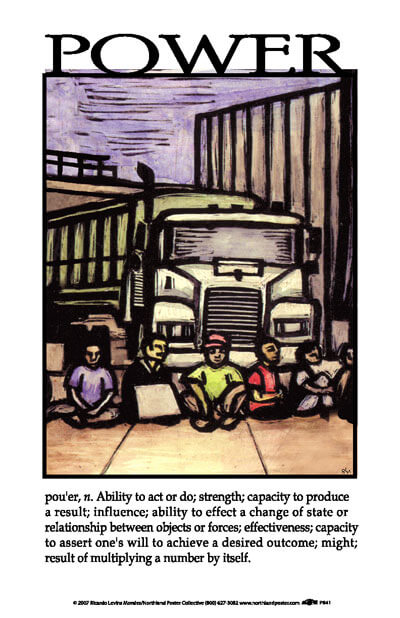

Historians regularly discuss the great ideas, insightful proposals, workable solutions, and moral righteousness of people in the past, knowing full well that, in terms of causing change in the real world, none of it matters until there is power behind it. That is the lesson conspicuous by its absence.

This is certainly not to disparage ideas or morality, but to put them in their proper context. Social security was an excellent idea in the eighteenth century when Tom Paine raised the essential idea, but generations passed before the people who stood to benefit had enough strength to tip the balance in favor of it. The critics of slavery were always right, but nothing changed until they found a way to put power behind it.

Working people do have the option of making our case in a venue where the rules are not written for us and the deck stacked against us. When we are organized and mobilized we have a power “greater than their hoarded gold.” Indeed, that long list of achievements—decent pay, unemployment benefits, retirements, weekends, a livable work week, and more—came down to the fear the owning class have for our numbers and what they can do. What is a labor movement that places no priority on moving laboring people—lots of them—and continuing to move as many of them as you can?

Scholars of American labor history should know this very well. Over a century ago, Jack London’s Iron Heel dropped its worker protagonist before millionaires of San Francisco’s Philomath Club, where, he bluntly laid out for them their own ineptness and greed. The shortcomings of capitalism, he told them, would force workers to take the power necessary to save themselves. “It is true that labor has from the beginning of history been in the dirt. And it is equally true that so long as you and yours and those that come after you have power, that labor shall remain in the dirt. . . Power will be the arbiter, as it always has been the arbiter.”

This need for numbers ties the idea of a labor movement inextricably to a wider democratic sensibility. Is democracy is to be nothing more than the periodic expression of a passive consumer preferences based on whatever regulated insights into our alternatives we are permitted? Nothing more than a popular ritual validation what the rulers want to do anyway? It is ultimately only by mobilizing those numbers and engaging them with us in shaping our future that we can make democracy more than a rhetorical appeal or a utopian vision.

The tried and true idea that expresses this is Solidarity. It provides the qualitative dimension of this observation about numbers. The lesson is that an injury to one ultimately does become an injury to all. In the end, solidarity for any particular workplace, industry or sector of the work force is a sad illusion when it’s not part of the broader solidarity of all who labor. This includes—and always has—issues of institutionalized racism, sexism, or homophobia. These represent class issues, not in the sense that saying this settles the question, but underscoring the responsibility to do all we can to make solidarity the practical touchstone of a labor movement. Union officialdom has translated this into a gentlemen’s agreement not to criticize each others’ policies, but that’s not really “solidarity,” which aims to win by learning from mistaken strategies and tactics and avoiding their repetition.

For generations, the official labor movement in the U.S. has opted for a series of what looked like shortcuts to bypass the entire messy process of building and sustaining a labor movement. We can, of course, do as we have done, playing a game of throwing our weight to one candidate or another or hiring lobbyists or advertising firms to persuade officeholders or aspiring officeholders. In those venues, to state the obvious, money buys the power and we never play such a game on anything like an equal playing field.

The efforts to protect public employee unionism in Wisconsin or Ohio were touted as great victories against the reactionaries. However, even the relatively smaller labor movements that exist in those states, such initiatives as those of Governors Walker and Kasich represented a great overreach beyond what even their self-described conservative base wanted. They should never have taken place, because the movement should have been flexing its power enough to keep anyone depending on public support for their jobs far too terrified to launch a corporate yuppie holy war on the standards of living and job security of working people. And after this attack began, the most effective response might have involved mobilizing unionists and their supporters in the largest, most visible, noisiest venues possible.

In the end, though, these governors and legislators happily functioned on behalf of the Koch Brothers, in full confidence that the AFL-CIO would do nothing to carry these issues beyond electoral politics. And that it would do nothing there that would jeopardize its involvement in that abusive plural marriage with the corporate Democrats. At no point did the labor movement in Wisconsin make any real attempt to mobilize anything like its memberships on behalf of anything other than getting out the vote. In Ohio, the unions relied almost entirely on lobbying, with periodic token mobilizations. The largest never brought a tenth of their total membership to Columbus.

The Ohio strategy centered on the petitioning campaign strategy aimed simply at repealing SB-5, the law attacking the bargaining rights of public employee unions in the state. At the end of the day, even success at putting such an effort into repealing what a reactionary state government does still leaves that government pass something just as objectionable, with a fraction of the effort you’ve had to put into repeal. Indeed, the fruits of this “victory” in Ohio left us with periodic talk of a new right-to-work law bouncing around the legislature. And, of course, the only way to protect public employee unionism is to replace the politicians who have been so responsive to corporate pressures unchecked with other politicians who are going to face the same pressures.

Worse, the AFL-CIO consciously chose to ask Ohio workers to protect only the right of public employees to collective bargaining. Even within the framework of a statewide petition, the campaign could have made an issue of the rights of ALL workers in the state to organize and exercise bargaining rights. I saw this idea of a petition to amend the state constitution come up several times—once from a Democratic member of the state legislature—only to be either ignored or shouted down. When they bothered to respond at all, union officials complained that it would take too many signatures (they wound up with more than enough).

They also argued that an attempt to make union membership a right for every worker in Ohio risked failure. Presumably Ohioans voting to sustain collective bargaining for public employees would vote against protecting such a right for themselves.

The key point was that in economic hard times, placing the idea of this right before voters across the state would have been a victory in and of itself. Getting unionism and its potential back in the public discussion could spark real struggle and significant membership growth. When the only labor historian in our little local of university faculty raised some very moderate suggestions about coupling the campaign to demonstrations, one of the state officers banged his hand on the table at me, and accused me of understanding nothing because I just didn’t respect all those heroic people in Cairo (who were presumably staying off the streets and meekly petitioning Hosni Mubarak).

The union leaderships did call rallies at Columbus, because they supplied a little media wallpaper for their work among the politicians. Although their largest demonstration claimed 20,000, they rarely needed more than 5,000 for these limited purposes. Simply put, this strategy relegated almost all of the 647,000 union members in Ohio to observer status. Under this strategy, unions continued to lose membership, including 43,000 gone since this much ballyhooed “victory” over SB-5. That meant that they had lost about 30% of the membership in a decade.[1] The citizens of a city that had lost that much population would be well justified in insisting upon rethinking the municipal priorities.

Again, a labor movement that goes for the numbers and the strength will find all sorts of things coming its direction. If Ohio unions had their emphasis on doubling their size, it’d find all sorts of “friends” in office, who are now weighing big contributions from corporations against and quietly deferential shrinking labor movement. And we’d have much broader choices as to how to deal with the likes of Governors Walker and Kasich.

I do not even venture into the despicable way in which union officials strove to squelch the Occupy movement in the interests of minimizing what it saw as “distractions” to the “pragmatic” preoccupation with reelecting Barrack Obama and legions of even more Nixonesque Democrats. Occupy militants talked excitedly when “the unions” started showing up, but it was only a few token souls led by their business agents sniffing for anything that needed to concern them.

As I pointed out at the time, if “the unions” really started showing up, Occupy wouldn’t have been camping in a park but actually occupying the entire city center. And this would have done so much more than focusing on the corporate intramural electoral games.

Rest assured. Hard times are coming and the present course of American union officialdom is adequate neither to save the standard of living of the American worker nor even to protect its own memberships. There will be no salvation in any amount of brainstorming for good ideas. Nor in any militant-sounding talk at whatever the decibel level. Nor in any of the delusional doubletalk blaming Republicans for policies that the Democrats voted for and are implementing. The more we persist in the attractively easy shortcuts and nostrums that have failed repeatedly, the more ground we lose that will have to be retaken at some point.

In the end, we will have to turn towards the prospect of building a genuine movement capable of mobilizing the masses of working people and grounded in a practical genuine sense of solidarity. That alone provides us the means not only to defend what we have won but hope for a better tomorrow.

The sooner the better. And that is where those who understand these lessons and are permitted to share them could make an important contribution.

[1] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union Membership in Ohio—2012,” http://www.bls.gov/ro5/unionoh.htm

1 Comment

Comments are closed.