Here are the most read essays of this year for the journal Labor: Studies in Working Class History. They are available for free until January 26, 2026. Check all of these out.

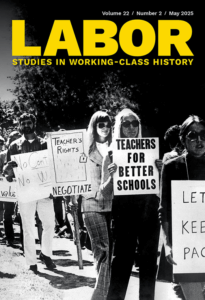

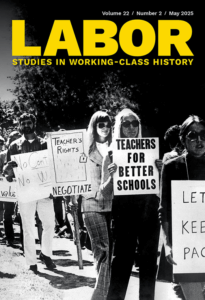

1. “Illinois Teachers and the Fight for Labor Rights: A Path Beyond the Liberal Order, 1966–1984” (vol. 22, no. 2) by Joseph Rathke

see the Labor Online blog about this essay

As US industrial unionism fell into crisis and the expansion of public sector unionism stagnated nationally in the 1970s, downstate Illinois teachers built a worker movement that only accelerated in the late 1970s and well into the 1980s, culminating in the passage of one of the strongest public sector collective bargaining laws in the United States in 1984. To understand the success of this campaign at such a dire moment, this article reexamines the geography of politics and class in Illinois in this era, centering the downstate industrial towns and cities that became the heart of the Illinois teachers’ movement amid deindustrialization. Influenced by the civil rights movement, the New Left, and legacies of radical industrial unionism in downstate Illinois, Illinois teachers seized control of the Illinois Education Association (IEA), a top-down professional advocacy organization, and transformed it into a rank-and-file union. They then pursued an aggressive, class-conscious political agenda culminating in statewide labor rights for teachers. This teachers’ movement emerged not as part of, but in opposition to, the declining liberal political institutions that scaffolded the labor establishment of the mid-twentieth century, which is why the IEA’s 1984 labor rights law succeeded in the same moment that labor liberalism crumbled.

2. “Mike Davis: The Road to City of Quartz and Beyond” (vol. 22, no. 2) by Nelson Lichtenstein

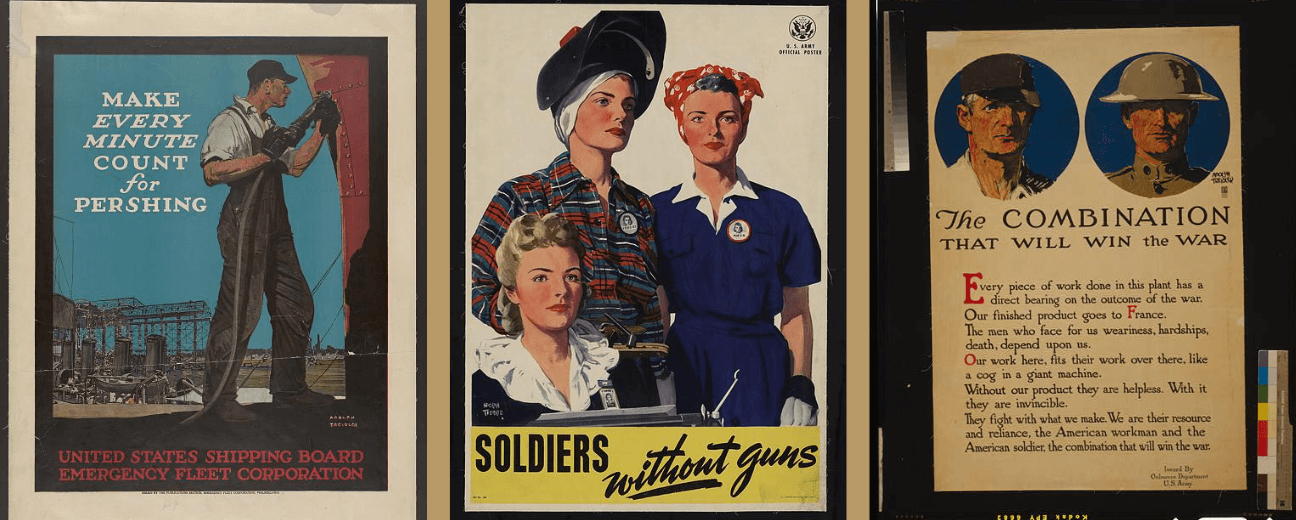

3. “Gotta Study War Work More” (vol. 22, no. 3) by Tejasvi Nagaraja

This essay is part of a roundtable on the subject of military and labor history, along with Justin Jackson’s essay listed below

Tej joined the recorded forum on the roundtable featuring all the authors as well for Labor Online

“How can we interpret the relationship between military history and labor history, between warfare and workers? To glimpse this terrain, we might consider a few reference points from the World War II period, involving Ronald Reagan, Claudia Jones, and Bertolt Brecht. Just before becoming a labor union president, Reagan was a captain in the Army Air Force’s First Motion Picture Unit. He narrated an Allied propaganda film about the Stilwell Road across the China-Burma-India Theater. US and UK footage showed African American, white American, British, Irish, African, Bengali, Kachin, and other workers “side by side,” building the vital supply route from Ledo to Kunming. The Allied workforce brought people “of all nations to work together.” Reagan noted that “men, women and children” were involved in strafing ops and guarding materiel, clearing land and driving trucks; from British pilots to Calcutta dockworkers and Assam farmworkers. US and UK empires relied on a multiethnic workforce of conscript and colonized servicemembers and employees. In this war of maneuver, military labor was the beating heart of waging and winning war.”

4. “Relitigating the New Deal: The Stakes of Current Constitutional Challenges to the NLRB” (vol. 22, no. 1) by Diana S. Reddy

“Is American labor law constitutional? The US Supreme Court resolved this question almost ninety years ago: yes, Congress can use law to promote worker power; and yes, Congress can entrust the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) with the authority to make labor law’s promises real. Today, however, twenty-first-century employers are reviving the lost constitutional claims of their twentieth-century counterparts, with shocking success, given how settled the law has been. According to employers in a spate of recent suits, the NLRB is rife with constitutional infirmities, afflicting its judges, its remedies, and potentially its inherent structure. In the conservative Fifth Circuit, courts are already ruling in employers’ favor. Ironically, these attacks can be seen as a testament to labor’s recent successes. The suits are defensive as much as offensive: a frenzied response by employers unnerved by labor’s political momentum and the Biden Board’s efficacy in making labor law work for workers again after decades of quiescence. What does the future hold for the Board? This short essay gives context and clarifies the stakes.”

5. “Class/War: Do Labor and Military History Work Together?” (vol. 22, no. 3) by Justin F. Jackson

Justin Jackson initiated this compelling forum, and this essay opens the discussion.  See Justin’s blog about his essay and the forum

See Justin’s blog about his essay and the forum

See Justin in the recorded forum with all the authors as well for Labor Online

“War was present at the making of the working class. It is thus no accident that modern theorists noticed affinities between labor and warfare. Famously, the Communist manifesto of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels popularized historical materialism by likening “class struggle” to armed conflict. Describing factory workers as “privates” of an “industrial army” serving under “a perfect hierarchy of officers and sergeants,” they implied that the bourgeoisie failed to realize that their command over the proletariat was actually preparing this new class for mutiny. A parallel paradox haunts what an expanding coterie of academics now describe as “military labor.” Some, deploying French philosopher Michel Foucault’s metaphysics of biopower, or how Cameroonian historian Achille Mbembe applies them in his critique of sovereignty as the power to kill, characterize soldiering as “necropolitical” work. Military laborers, argues literary scholar Jin-kyung Lee, become both agents of state violence and its “potential victims.” Yet historians’ multiplying discussions of military labor have not moved much beyond metaphors. If the lexicon of the labor movement betrays residues of martial culture, from terms such as rank and file to picket lines, acknowledgment that troops casually refer to combat and its terrors as “work” remains gestural.1 Nor has labor scholars’ interest in warfare as work inspired military historians to contemplate war as labor.”