To protest the ongoing genocide in Gaza, dockworkers in Genoa, Italy attempted to convince their fellow workers in ports across Europe and North Africa to join them in boycotting all Israeli cargo, including but not limited to military cargo. Theirs was among the boldest and potentially most effective actions that can possibly be taken by civil society in shaping international politics. It should come as no surprise to labor historians that there’s a history to that.

My article, “’Scrap Iron Becomes Bullets’: When Dockers Fought Fascism with Direct Action,” in the September issue of Labor explores dockworkers long history of solidarity activism in support of peoples fighting authoritarianism, fascism, imperialism, and racism. Since dockworkers labor at “choke points” in the global supply chain, they–and other workers in the transportation industry but especially shipping–can interrupt trade and, thus, the world economy itself.

Since their founding in the 1930s, the International Longshore & Warehouse Union (ILWU), and particularly its San Francisco Bay Area branch, Local 10, has periodically injected its radical, working-class perspective into global politics. They have done so in various ways but especially by refusing to unload cargo from or load ships intended for fascist, imperialist, and racist regimes. Having written extensively about ILWU Local 10’s longest campaign, against apartheid South Africa, my latest article examines two other, far less well known, efforts.

In 1937, imperial Japan launched the Second Sino-Japanese War, expanding the invasion of China that Japan had begun in 1931. Chinese and Chinese Americans in San Francisco, long the US Pacific Coast’s biggest and most important port, responded with a series of protests including at piers where the loading of metal and other materials aboard ships intended for Japan. The ILWU had just been officially born, out of the fires of its successful coastwide Big Strike in 1934.

Many founding members and leaders of the ILWU, including its legendary president Harry Bridges, were Communists, Socialists, Trotskyists, Wobblies, and other sorts of leftists; hence they paid attention to international affairs and sought to shape them via their own workplace activism. In 1936, in their first such action, they refused to load cargo aboard an Italian vessel to protest fascist Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia the year prior. Similarly, some SF longshoremen traveled to Spain to volunteer in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade which had been founded to support the Spanish republic against a military coup d’etat that had expanded into a civil war that foreshadowed World War II.

In 1938 and on several dozen occasions over the next few years, Local 10 refused to cross Chinese pickets, in effect boycotting all cargo slated for Japan. Similar actions occurred at least a few times at other ILWU-controlled ports including Los Angeles and Seattle. San Francisco longshoremen did so despite their overwhelmingly white membership and, fascinatingly, with a Japanese Communist rank-and-filer, Karl Yoneda, coordinating these boycotts with Chinese Americans. At the time, the ILWU, including Yoneda, were fiercely criticized for mixing politics and work. After the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor in 1941, however, the ILWU had proven that being prematurely antifascist was, in fact, the way.

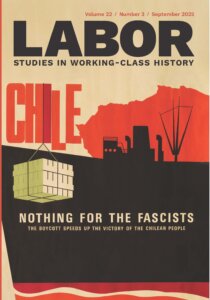

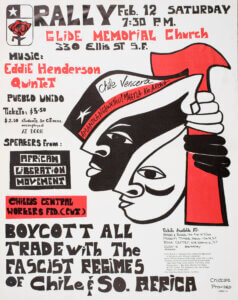

In the 1970s, the ILWU took a principled stands against authoritarianism in Chile where, in 1973, a coup d’etat led Augusto Pinochet had overthrown the democratically elected socialist government led by Salvador Allende. Before that coup, which had the active support of the U.S. government and tacit support of the AFL-CIO, the ILWU had begun developing friendly relations with the Chilean labor movement. The ILWU condemned this shocking coup—as did many unions, civil society groups, and governments around the world. In 1978, after a member discovered U.S. military supplies intended for Chile on a San Francisco pier, Local 10 activists built a coalition to support the union’s successful boycott of those US military supplies. In coordination with Chilean and other solidarity activists as well as Democratic Party allies in Congress, the ILWU ultimately helped push U.S. foreign policy away from further military and economic aid for Chile.

In both campaigns, rank-and-file activists led the fight, pulling the international leadership of the ILWU to become more radical. As has occurred in other struggles, in retrospect Local 10’s actions have been deemed effective and even noble; accordingly, after the fact a great many praised actions that—at the time—were controversial and quite bold. In particular, the union’s anti-apartheid activism has become part of its lore.

These dockworkers, and others like them in ports around the world, demonstrated their commitment to labor internationalism through work stoppages—what the Wobblies called direct action at the point of production.

These historic actions share much in common with today’s dockworkers in Genoa who have led hundreds of thousands of other Italian workers to engage in several general strikes in solidarity with Palestine. The Genoese also are working in concert with dockers from Livorno, Marseilles, Piraeus, Barcelona, Gothenburg, Casablanca, Tangier, and other Mediterranean and Northern European ports.

Conspicuously absent is the ILWU. Impassioned attempts by activists in Local 10 and some other locals failed to pass a resolution in solidarity with Palestine at last year’s International Convention. (Far less surprising is the silence of their sometime friend/sometime rival, the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), which represents dockworkers on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of Canada and the United States.) For now, at least, the ILWU—including its most activist local in the San Francisco Bay Area–has passed the baton to their fellow (dock)workers on the northern and southern coasts of the Mediterranean.

The campaigns of dockworkers to oppose imperialism by Japan and fascism in Chile resonate today, as they did in the past. They speak to how ordinary people, when organized on the job, can shape their world.