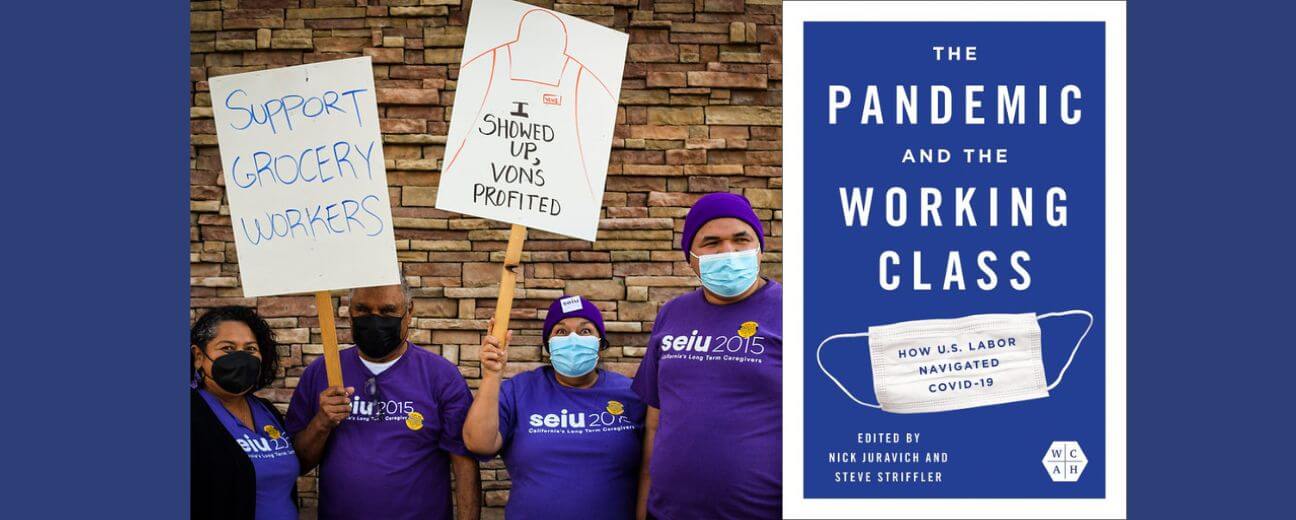

As part of our ongoing series of interviews with authors and editors of books in labor and working-class history, Jacob Remes spoke to UMass Boston professors Steve Striffler and Nick Juravich, the editors of The Pandemic and the Working Class (University of Illinois Press).

Your book captures some of the political hope a lot of us felt during the height of the pandemic – the idea that different and better things were possible, and that the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter uprisings, and the “Great Resignation” had given workers more power. One of the things I’ve been wrestling with — I wrote about it on this very blog — is how to account for the loss of that moment. Do you think you and the authors in your book have ways for us to understand?

Steve: The pandemic was a “moment” in a couple senses, which the book captures. It became clear very quickly that government — at local, state, and national levels — was not capable of dealing with a crisis of this magnitude. Decades of neoliberalism, which had gutted the state in general and public goods like healthcare and education in particular, ensured that government would not be able to respond in a satisfactory way to this level of health and economic crisis — and this would leave working people horribly exposed. Alongside this failed response was the extent to which the pandemic revealed (or reminded us) how little many employers actually cared about their workers. This was in sharp relief during the pandemic, as was how effective the rich were at insulating themselves from the health crisis while expanding their wealth. The book captures this in that it explores the impact of the pandemic on different groups of workers, including those who were quickly laid off en masse, losing not only their livelihood but their health insurance, as well as those who remained in workplaces run by employers who seemed remarkably unconcerned with worker safety. And yet, at the same time as working people were experiencing government incapacity and employer callousness, they also learned how much the government could do once mobilized on behalf of working people. This came not simply in the form of cutting checks to keep people afloat during the pandemic (where did all the money come from!!), which started under Trump, but continued during the first years of the Biden administration when we saw some remarkable shifts in policy making approaches. Landmark legislation — the American Rescue Plan, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, etc. — made it seem like policies were (or could be) guided by the goal of rebalancing power in the economy in a more equitable way. At the very least, it was in strong contrast with neoliberalism’s main dogma that the government should not intervene in the economy (at least not to help working people). There was, in this sense, a shift in how people understood what government can do. And there was also a shift in how they understood their employers, their own relationship to work, and even inequality — which partially explains the significant expansion of work-related organizing during and after the pandemic, even if all of this was building for some time.

Following from this, I would say the book has two takeaways that are suggestive about that moment going forward. First, to the extent that the Biden presidency is now looking like nothing more than some sort of brief blip between two Trump terms, it seems that the Democrats once again showed us who they are in the sense of not having the political orientation/will to seize a moment when it falls right into their laps. Despite all the government spending under Biden, and not insignificant support for organized labor, the Democrats really did not go after the rich and their wealth in any significant way during a moment when public support for such a redistributive project was significant. This partly accounts for the “loss of the moment” in the sense that working people, and the labor movement, did not have the capacity to force the Democrats in a direction that they have no inclination in going towards on their own. Second, and following this, although it is unclear how much of a moment the pandemic ever really represented (at least in terms of producing a real political break that would shift the balance of power in our favor), it definitely played a role in encouraging workers both within and beyond labor unions to take the fight to their bosses and demand more from government. What I take from the book, and its focus on organizing, is that much of this will continue, and no doubt evolve in unexpected ways, even during what promises to be a politically bleak period.

Nick: There’s no way to sugarcoat how bad things look right now, and yet, to answer your question, I actually do take a lot of hope both from what’s in the book and from where it has directed my attention. To give two examples:

Kathryn Meyer has a great chapter in the volume, “Disability Justice and the Education Labor Movement during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” that looks at the Boston Teachers Union’s efforts to prioritize the needs of students with disabilities and their families during the pandemic, both in the immediate moment when the closure of school meant the loss of key services and interactions, on up to the way BTU fought for what they term “inclusion done right” in their 2021 contract. It’s a fascinating, detailed look at the nuts-and-bolts specifics of how BTU has embraced these larger trends in educator unionism: bargaining for the common good and social movement unionism.

Educator unions were on a roll in the years immediately before the pandemic, as LaborOnline readers will know, including the remarkable #RedforEd wave of 2018 and the successful strikes of both United Teachers Los Angeles and the Chicago Teachers Union in 2019. In 2019, we also had our first teachers’ strike in Massachusetts in 12 years, when Dedham educators walked out and won a great contract. The bipartisan world of neoliberal education reform seemed to be crumbling, both under pressure from unions and the left and because the first Trump administration, with Betsy DeVos at the helm, had taken so many of these “market-based” ideas to their ugliest extremes.

But then, as school closures became a pandemic reality, an elite narrative quickly emerged among the same centrist pundits and politicians who’ve spent the past couple of decades trashing teacher unions and extolling “ed reform”: educator unions were to blame for school closures! Surely, these folks presumed (and still do), the public would learn to hate teacher unions all over again, as they did during the onslaught of anti-union messaging that accompanied the rise of choice, charters, and high-stakes testing in the aughts. All the kids whose high school experiences were disrupted, all those parents forced to juggle school-and-work-from home … none of them would ever support educator unions again, would they?

Except here in Massachusetts — where there is plenty of deep-pocketed anti-union messaging — that just hasn’t been true. Our union, the Massachusetts Teachers Association, has had locals out on strike every year since 2019, and they’ve won huge gains, often for the educators and students who need them most. Building on Meyer’s chapter, many of these campaigns have focused on winning living wages for paraprofessional educators (known, in NEA contexts, as education support professionals, or ESPs), and they, in turn, serve students with disabilities and other “special needs” (this is also an area or scholarly interest for me). The “greedy selfish teachers” narrative just doesn’t land when the people on the picket lines are asking to make just $40,000 a year in Greater Boston, and when the students and families they serve are standing side by side with them.

In 2019, when Dedham went on strike, most of my students didn’t know much about teacher strikes, and they definitely didn’t expect to learn about one so close to Boston. By 2022, I had a student stand up in lecture to say “I’m a graduate of Malden High School, I’ve been on those picket lines with my high school teachers, let me tell you all about it.” This past fall, I had another student in that same big lecture class talk about joining his sister — one of those paraeducators fighting for living wages and respect — on the picket lines up in Beverly. To return to the focus of Meyer’s chapter, the BTU just settled its 2024 contract (it took until April of 2025) with 23-31% raises for paras, all of whom will make over $40k/year by 2027.

I know Massachusetts is a very particular place, and I don’t mean to suggest it’s representative of the entire nation. Still, despite every effort on the part of our centrist punditry and politicians to “not let the crisis go to waste” (to paraphrase that failed mayor and school privatizer Rahm Emmanuel), they’re still losing. Meyer’s chapter helps us understand why.

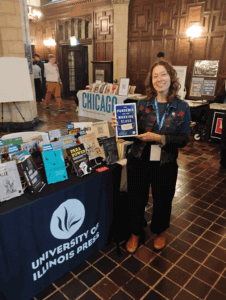

To broaden the scope, the chapter right before Meyer’s is by Kathleen Brown, a graduate student, worker, and organizer at Michigan. It’s titled “No Cuts–No Cops–No COVID: The Graduate Employees’ Pandemic Strike at the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor.” I saw Kathleen at the LAWCHA conference this past June, and even snapped a picture of her with the book. More importantly, she shared just how significant the 2020 strike she chronicled remains for graduate workers (and all workers, really) at Michigan, both in how it informed their 2023 strike and how it continues to shape their organizing and sense of what’s possible. It’s worth noting here that both the Massachusetts strikes I mentioned and the Michigan strikes are illegal under state law, but that’s not stopping the MTA and it’s not stopping the Michigan graduate students, either.

Kathleen was at LAWCHA, in part, to connect with grad workers organizing across the country, and their session on Thursday, as I understand it, was one of the most important parts of the whole conference (it feels pertinent, here, to note that Kathyrn Meyer, too, is a graduate student/worker/organizer). Whether in their particular actions on campuses all over or in publications like Long Haul, these graduate workers/organizers/scholars/ theorists are leading the way for us as all of higher education comes under attack.

One other question: What are your current research and writing projects? Do you think your scholarly or teaching interests – your work as academic workers – have been shaped by Covid?

Steve: I am working on a history of food activism that deals entirely with time periods prior to the pandemic. However, the pandemic reinforced a direction I was already headed in — and that is to expand my own understanding of what constitutes food-related work to include not only field labor and restaurant workers, but all the other work/workers involved in getting food from the fields into our homes, restaurants, cafeterias, food trucks, etc. That work, and those workers, became much more visible during the pandemic.

Nick: I’ve been working closely with the Boston Teachers Union for a number of years now on a public history project that’s taught me a great deal, not just about the BTU and educator unionism but about the possibilities and power of doing public history with working people and their unions. This actually links to the ideas and observations in the third chapter in our section on “The Education Industry” in the volume, which is Lia Warner’s essay on “Archival Labor and Labor Power: Using COVID Collections to Rethink History Making and the Labor Movement.”

Lia does a wonderful job of reflecting on the ways that in-the-moment archival work took different directions for different groups of people depending on their positions and processes, and how that, in turn, shaped the way she and her colleagues thought about their own work and their role in struggles to come. I’d like to imagine that I’ll manage to put together a proper book from the BTU work at some point, but in the meantime, I’m hoping to gather my thoughts on the work we’ve done in an essay or two, much like Lia’s.

Authors

-

Jacob Remes is a historian of modern North America with a focus on urban disasters, working-class organizations, and migration. He is a founding co-editor of the Journal of Disaster Studies, the co-editor, with Andy Horowitz, of Critical Disaster Studies (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), and a series co-editor of the Penn Press book series Critical Studies of Risk and Disaster. His first book, Disaster Citizenship: Survivors, Solidarity, and Power in the Progressive Era (University of Illinois Press, 2016) examined the working class response to and experience of the Salem, Massachusetts, Fire of 1914 and the Halifax, Nova Scotia, Explosion of 1917. He has also written scholarly articles on a variety of other subjects ranging from interwar Social Catholicism to Indigenous land rights to transnational printers in the 19th century. His popular writing on subjects relating to his research has appeared in the Nation, Atlantic, Time, Salon, and elsewhere. Before coming to Gallatin,

-

Nick Juravich is an Associate Professor of History and Labor Studies and the Associate Director of the Labor Resource Center at UMass Boston. He is the author of Para Power: How Paraprofessional Labor Changed Education (Illinois Press, 2024) and the co-editor, with Steve Striffler, of The Pandemic and the Working Class: How U.S. Labor Navigated COVID-19 (Illinois Press, 2025). He is a member of the Faculty Staff Union, a local of the Massachusetts Teachers Association.

-