A much-overlooked part of the rise of the Communist Party as the leading Left organization in the mid twentieth century is that it produced a robust network of schools for workers. An overview of these schools conveys the effort to instill in workers a class-conscious education. These schools countered dominant pedagogy and traditional education.

Early in its history the Party argued that traditional schools were agents of indoctrination, designed to instill quiescent, interchangeable workers. “The primary motive of the institutions of so-called free education is to turn out as large a number of obedient patriotic wage slaves …” the Daily Worker argued in 1925.

To counter that trend, the Party established a network of “people’s universities”: workers’ schools that, as the Chicago’s Workers School announced, would, “equip the workers with the knowledge and understanding of Marxism-Leninism” so that worker-students could engage in “militant struggle … toward the decisive proletarian victory.” New York’s Jefferson School and Chicago’s Abraham Lincoln School taught some of the country’s first courses in African American history and labor and working-class history. They championed a humanistic form of adult education for “workers of hand and brain.”

The flagship was the New York Workers School, which offered courses in the Principles of Communism, Marxism-Leninism, and Historical Materialism, and saw its mission as preparing pupils for their role in bringing about the workers’ state. School Director Bertram Wolfe in 1925 declared his school was “a part of and subordinate to the political agitation and propaganda of the party, to be designed to definitively serve the party’s needs in its major campaigns. … This is the spirit in which we must approach our work.” Nine years later, the School’s new Director, Abraham Markoff, noted Earl Browder “emphasized the importance of bringing about a real Bolshevik result in the teaching of Marxism-Leninism in our schools.” General theory in courses, he stressed, “must be linked up with the immediate problems and developments of today.”

While the class struggle remained front and center, already by the mid-1930s schools were expanding in two ways: the curricula soon offered many courses in the broader humanities. And workers schools taught children and adults not just in large cities but in many smaller places as well.

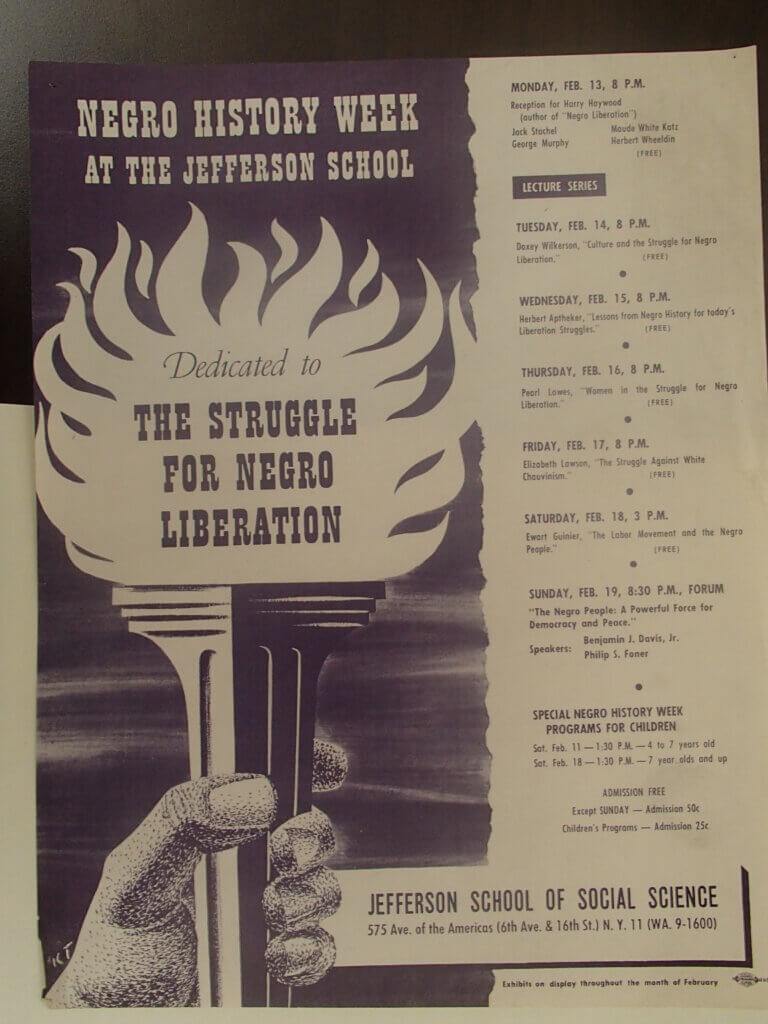

A weekly Daily Worker column, “What’s Doing in the Workers Schools of the U.S.” demonstrated the depth of offerings, pedagogical and geographical. Already by 1934, recent Communist Vice-President Candidate James Ford and James Allen were offering a course on “Problems of the Negro Liberation Movement,” which covered “Negro” history from colonial times to the present, highlighting “the revolutionary traditions of the Negro people which have been buried by bourgeois and reformist historians.” The schools offered a mix of ethnic culture, training in public speaking and union organizing, and history lessons from America’s submerged ethno-racial and working-class past. The Harlem Workers’ School in 1934 offered a course on “History of the Negro in America,” with lectures on “What has Capitalism Done for the Negro?”

As early as 1934, similar courses on Black history as well as anti-colonial history were taught at workers’ schools in Saint Louis; Brownsville, Brooklyn; Los Angeles; Detroit; Buffalo, even Newport, Illinois. The valorization of African American history continued in the schools as the Party swung into its Popular Front period. Schools after 1935 claimed prominent historical figures as progressive icons; they were urged in 1936 to stress “the revolutionary historic role of Lincoln” and to “link up their present struggle with its revolutionary traditions and past” lest “fascist falsifiers” claim “all that is valuable in the historical past of the nation,” so “that the fascists may bamboozle the masses …” Workers’ Schools embraced Lincoln, as well as “that great liberationist son of the Negro people, Frederick Douglass,” as part of a progressive American genealogy.

This emphasis on progressive Americanism led to some unintended ironies. Popular Front Communists at New York’s Jefferson School celebrated both Thomas Jefferson and “Negro slave revolts” as progressive history. What was unusual, though, was that schools offered courses by historian Herbert Aptheker on “Negro Slave Revolts” at all. Elizabeth Lawson’s 1939 course on the “History of the American Negro People” offered some of the first rejoinders to the dominant public-school canard on Reconstruction as “the Era of Negro Misrule.” Likewise, she presented Gabriel Prosser and Denmark Vesey as heroes, surely a dissenting view in the 1930s.

Other innovative humanities courses, while anchored in a Marxist perspective, expanded workers’ horizons. New York’s school in 1934 offered courses in “Social Forces in American History;” “History of Science and Technology;” “Origin of Man and Civilization;” “Colonial Questions,” and “Revolutionary Interpretation of Modern Literature.” Los Angeles students could take “Emancipation of Women,” taught by “a specialist in social medicine and women’s hygiene.” At Chicago’s Workers School, courses in art and literature were hosted in 1934; drawing and illustration and dramatics were already proving popular with children and adults enrolled in Cleveland, although that school also offered Russian History. Workers schools in Queens; Crown Heights, Brooklyn; Harlem, and Detroit had drama and art courses. At Cleveland’s Workers School, the library contained many novels such as Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones to enhance courses in literature, but no works, Markoff lamented, by Lenin or Engels. Some students evidently gravitated to workers schools for expanded horizons in literature, art, or the theater. The schools already offered a proto-course in adult education.

This was a new direction from the 1920s, when New York Workers’ School instructors derided “so-called workers’ education movements that wish to bring bourgeois ‘culture’ to the working class through the aid of bourgeois professors,” mocking “courses in appreciation of music, literary criticism and aesthetic dancing” as irrelevant to the proper training for revolutionary workers. Michael Denning has noted that during the Popular Front, culture was reconceived by the left as a force for progressive political change. From the mid-1930s, workers’ schools abandoned earlier fixation on praxis-driven Marxist courses, and offered a broad array of courses in music, literature, and art.

The Party’s workers schools were capacious, too, in their geographical reach. The largest number of courses were offered at the New York school, and course material was available to interested parties elsewhere if they contacted Markoff at 35 East 12th Street. But workers schools operated in industrial centers such as Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and Los Angeles, but also in Eugene, Oregon; Sacramento; Jersey City and Bayonne; Oklahoma City; Lancaster, Pennsylvania; Worcester, Massachusetts, and New Brunswick, New Jersey. Most intriguing was the announcement in May 1934 of a “Farm School on Wheels,” to offer classes on organizing and rural problems in North and South Dakota and elsewhere. A similar course had already been offered in Arkansas.

By World War II, the schools were part of a left-wing network, which served as “a people’s university,” as the Polish newspaper Głos Ludowy labeled Chicago’s Abraham Lincoln School. In 1942 more than 4,000 black, white and Hispanic men and women flocked to classes at Lincoln, taking courses in “The People’s War; Structure of Fascism; Propaganda Analysis; Spanish; Basic English; Russian; French; Economics; Philosophy; History; Psychology; Art; Music; Writing for Short Story; Newspaper and Radio; Public Speaking; Labor Problems; History and Culture of Racial and National Groups.”

By World War II workers’ schools refashioned themselves as advocates of a progressive Americanism, with talk of revolution downplayed. Chicago’s Abraham Lincoln in 1944 now advertised its goal as “For a national unity and a united world through people’s education.” Education, the school argued, must be “a truly American method of preserving and extending our democracy through frank, objective discussion.” This was a far cry from “the decisive proletarian victory” the school’s predecessor had demanded less than a decade earlier. Still, courses in Negro Liberation taught by William Patterson remained revolutionary in their content, as arguably were courses in the lessons of the Four Freedoms, anti-colonialism, and the necessity for an enduring Soviet-American friendship. Lincoln School by war’s end offered courses in progressive humanities including “Art as a Weapon;” and “How Writers Fought for Freedom,” which examined Rabelais, Cervantes, Shakespeare and Milton. Proletarian novelist Jack Conroy taught “Problems of the Individual Writer.”

After 1944 the Jefferson School of Social Science in New York became the premier workers’ school. It offered courses in African American, Latin American, and U.S. labor history by scholars such as Aptheker, Lawson, and the Foner brothers, leftist professors fired from the City College of New York in 1941 for their political beliefs. Aptheker and Philip Foner’s emphasis on the salience of slave revolts and Frederick Douglass to America’s freedom story was certainly a counterhegemonic pedagogy at a time when public schools persistently cast abolitionists as unstable, dangerously violent extremists–and claimed slavery was a benign institution.

This mixing of progressive culture with Marxist analysis continued into the 1950s. Jefferson did not hide its aim. The school’s capstone was the Institute of Marxist Studies, and history classes used a counterhegemonic analysis of workers’ militancy and anti-racism. But Jefferson and other schools also brought literature and art to “workers of hand and brain.” Jefferson offered a range of non-credit classes in art, literature, music, and sculpture to workers interested in education and culture for their own sake. By 1950 classes included “Mystery Story Writing” with Dashiell Hammett, painting instruction by Philip Evergood or Anton Refregier, and painting and drawing taught by Hugo Gellert and Charles White. Creative fiction classes were taught by Myra Page and Howard Fast. The course catalogue labeled its varied classes, whether in painting, Marxism, Black History, Shakespeare, or creative writing, as “Know-How for Progressives.” The school argued, “Students come to the Jefferson School solely because they believe the school will help them understand the world we live in.”

Socially conscious pedagogy, too, endured at the Jeff, with courses in “The Puerto Rican National Minority” by Jesús Colón; “U.S. History Schools Don’t Teach” by Aptheker; “History of the African Slave Trade” by W.E.B. DuBois, and “China, India and Africa: New Role in World Politics” by Alphaeus Hunton. The Jefferson School catered to workers interested in education for education’s sake.

These “People’s Universities,” as the Jefferson’s directors called the school, helped workers “achieve that education which can enable them to change their world through ever better understanding of it.” Three years later, the school reiterated its commitment to educate “workers of hand and brain – for it knows that these are not only the most numerous group in our society, but also that in their thought and struggles lies the promise of the future.” At a celebratory banquet on its fourth anniversary (attended by Paul Robeson, W.E.B. DuBois and others, the school proclaimed, “Ideas – when the people take hold of them – can change the world!”

For a time, it seemed progressive pedagogy was a growth industry. The Jeff developed annexes in Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens, and made its course outlines in anti-colonialism, Black history, and labor available to Newark’s Walt Whitman School and White Plains’ Tom Paine School. The moderate Republican New York Herald Tribune in 1945 approvingly reported the Jefferson School had annually enrolled 14,000 students and that the “Leftist School [was] Copied in Seven Other Cities.” The “experiment in adult education” was, the paper noted, regarded by the Jeff’s directors as “a strong trend … toward realization of the dream of a ‘people’s university’ – an educational forum geared to the ‘needs of citizenship in a democracy,’ rather than to ‘self-development’ or ‘heightened individual awareness.’” The bemused Herald Tribune wondered, “Does this mean that a new educational yeast is beginning to leaven in the nation?”

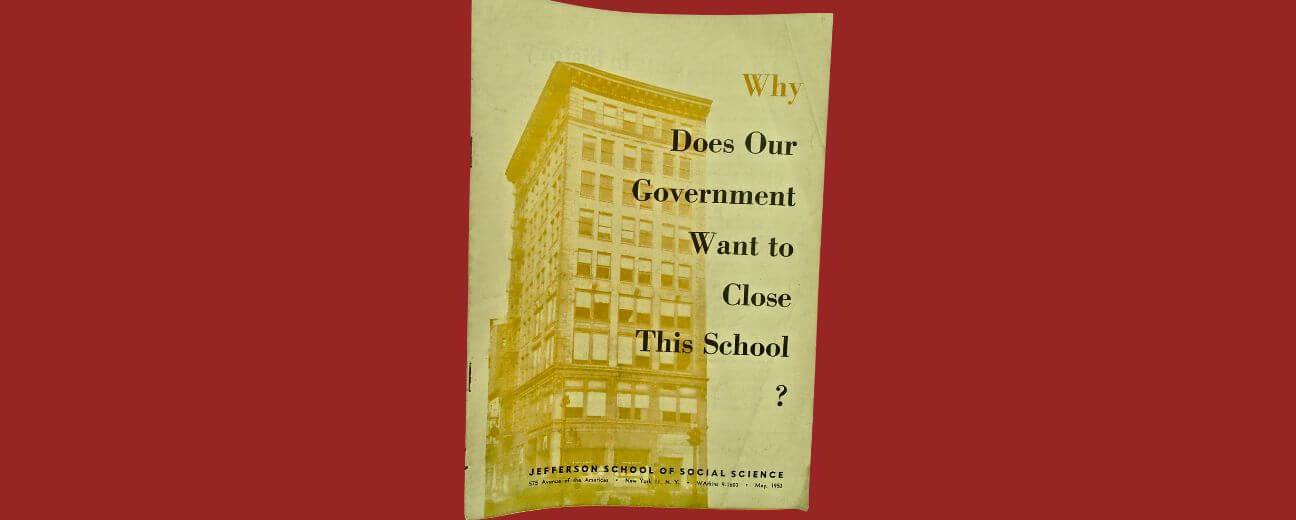

Within a few years, the paper had its answer. Progressive schools were targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee and the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations. Schools were stigmatized for preaching such heresy as anti-colonialism or scientific Marxism but also for teaching racial equality. The Jefferson School and other “people’s universities” faced declining enrollments and crushing legal bills. The school’s directors pleaded with the public, “Don’t Let McCarthyism Darken the Halls of Learning,” but it closed by the end of 1956. In announcing its demise, Jefferson’s board was “confident the understanding and inspiration provided by the School will live on in the minds of its many thousands of students, and will continue to be reflected in their daily lives.”

Many school alumni indeed continued espousing civil rights, peace and other causes, and alternative schools rose again through the efforts of SDS, the Mississippi Freedom Summer and other liberationist organizations such as New York’s 1965-68 Free University. The Workers’ Schools then offer a liberating, pedagogical genealogy to counter contemporary privatized, marketized education mania. In a neo-Dickensian era where monetization has infested the liberal arts, we must look to an earlier era’s “people’s university” for instruction.

Sources

Daily Worker.

Michael Denning, The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Verso, 1997.)

Głos Ludowy.

Library of Congress, CPUSA microfilm collection.

Ľudový denník.

New York University, Tamiment-Wagner Library, CPUSA collection.

New York University, Tamiment-Wagner Library, Jefferson School of Social Science Papers.

New York University, Tamiment-WGNER Library, Printed Ephemera Collection.

Clarence Taylor, Reds at the Blackboard: Communism, Civil Rights, and the New York City Teachers Union (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 42, 223.

Author

-

Robert Zecker is a Professor of History at St. Francis Xavier University. His research and teaching focus on US immigration history. He is the author of America’s Immigrant Press: How the Slovaks Were Taught to Think Like White People (New York: Continuum, 2011).