Co-authors: James Barrett, Shelton Stromquist

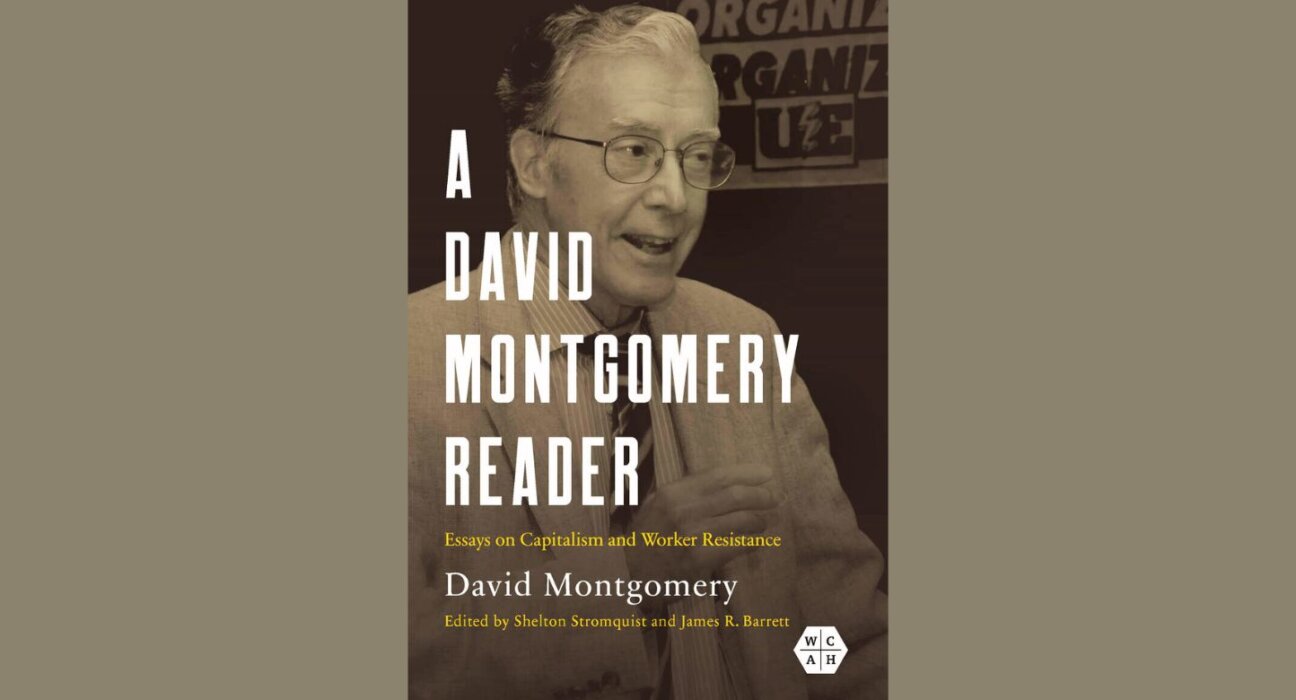

David Montgomery was a founder of the modern field of labor history. Even long after his death, the field remains molded by his methodologies and insights. So John Enyeart was pleased to interview two leading scholars of the field, Shelton Stromquist and James Barrett, about their new edited collection of David Montgomery. Shelton Stromquist and James R. Barrett, A David Montgomery Reader: Essays on Capitalism and Worker Resistance, University of Illinois Press, 2024 The collection comprises both published and unpublished essays. These essays trace “Montgomery’s distinct voice and approach while providing a crucial window into an era that changed the ways scholars and the public understood working people’s place in American history. “

Q and A with Shel Stromquist and Jim Barrett

Why do the book at all? What does David’s legacy seem to be?

David Montgomery was a key architect of the “new labor history” and a “bottom, up” approach to the social history of the working class which transformed our understanding of workers’ lives in the broader sweep of American history.

The essays, which span the period from the early 1960s to the time of his death in 2011, allow the reader to gauge Montgomery’s impact, but also to trace the evolution of the field. A David Montgomery Reader: Essays on Capitalism and Worker Resistance combines many of David’s most important journal articles with a selection of his unpublished pieces and some essays that appeared in more obscure locations. (A comprehensive bibliography provides a list of his publications in scores of venues.) Four broad themes emerge in Montgomery’s work: class formation from the colonial years through the postwar era; the social relations of production in many different workplace settings; the diversity of working-class experience and the ways in which that diversity shaped collective action and politics; and above all, the pervasiveness of class experience in the lives of working people. Taken together, the essays convey a remarkable tableau of a beleaguered but resilient and creative working class across the generations.

We have tried to assess Montgomery’s legacy in our introduction and a series of headnotes that frame the essays. That legacy turns out to be broader than many of us might imagine. On the one hand, he did indeed focus on the social relations of production, but he saw the experience of class going well beyond the workplace into communities and family spaces. It was a pervasive influence on the lives of working people. “If all we see,” he told interviewers more than forty years ago, “is what’s going on in the workplace, we are going to miss a great deal.”

Although the connections in his work between race, ethnicity, gender, and other forms of social difference have not always been recognized, documenting the extreme diversity of class experience was a major project in his own work and that of his students. His interest in race and racism was abiding and shows through in much of his work over the years. Documenting this diversity and these divisions in detail lent his work what we might see as a “pointillist” quality. No one who has read Montgomery or listened to his syntheses of papers at conferences could fail to be impressed by his ability to stitch the pieces together and to generalize at a level that escapes most of us, yet these broad syntheses were never unqualified or without contradiction. History yielded no “typical” working-class experience for Montgomery; the story was never simple.

David’s roots were in the postwar labor and socialist movements. He spent many years as a skilled machinist and local union activist, and he remained politically engaged throughout his life. This experience grounded and enriched his research and writing. A biographical sketch in the book lays out some of this activism, and the volume includes several of David’s more political essays, including his classic Radical America pamphlet “What’s Happening to the American Worker” (1970), part of his conversation with New Left activists many of whom joined him in the field of working-class history in the 1970s and 1980s.

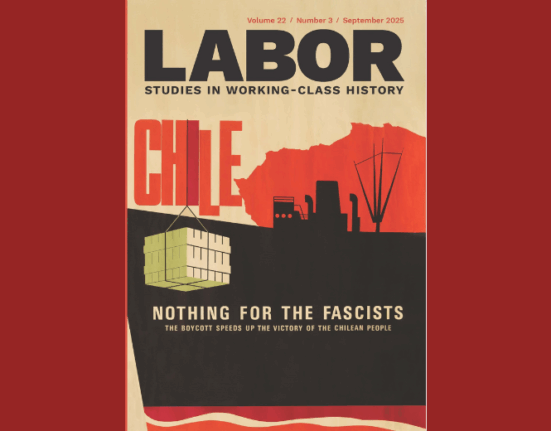

Owing in part to his early exposure to Marxism, Montgomery always wrote and taught in a broad, comparative framework. His seminars at Pittsburgh and Yale incorporated readings from various societies, and he maintained contacts with working-class scholars around the world. In his research and writing he took an explicitly global turn in some of his last essays. As Julie Greene notes, “he turned sharply toward a more rigorous exploration of global labor history and the ways that empire and global capitalism intersected with US labor and working-class history.”

How and why did this book happen?

After Dave Montgomery’s sudden death in 2011, we both realized that he had some unfinished academic business with which we might help. We and others had encouraged him over the years to publish a collection of his essays. And although he expressed some interest, other academic projects always seemed to be more pressing. So, beginning in 2014, with encouragement from his wife Marty, we began to think more seriously about what a volume of his essays, published posthumously, might look like. Shel spent some time reviewing his collected papers at the Tamiment Institute/NYU in early 2015 and found a number of fascinating papers and talks that had never been published. Although we both had many ongoing academic projects distracting us from pushing ahead with the project, we managed to pull together a preliminary table of contents, ran the idea by others, and contacted the University of Illinois Press about its interest in publishing such a volume. Given David’s role as a founding editor of “Working Class in American History” book series, Illinois seemed the obvious choice, and Laurie Matheson and the editors of the series were receptive.

Beyond selecting the essays (a combination of many of his most important published essays and a few of the unpublished ones) and crafting an evolving table of contents, we faced the technical challenge of creating a unified manuscript in digital form from a variety of pre-digital formats. With technical help at various stages from UI Press staff and staff of the University of Iowa History Department, we managed to create serviceable scans that nevertheless required more rounds of editing than we ever imagined. With generous help of many, we gathered permissions to republish the previously published work and collected photographs and their permissions that brought us to this cusp of publication.

What were some of Montgomery’s key conceptual insights?

The book examines the arc of his scholarship and the evolving nature of his engagement with the American working class. His powerful insights into the ways in which skilled workers contested for “control” over the social relations of production at key junctures in the evolution of capitalism drew inspiration from his encounters with British shop stewards during his two-year sojourn with E.P. Thompson at Warwick University. Those insights blended with his own work experience as a skilled machinist in a very different time and gave him a conceptual framework for challenging the rigid Commons/Perlman naturalization of what they understood to be skilled workers’ “scarcity consciousness” and the narrow and defensive trade unionism it bred. He understood “workers’ control” to be an open-ended, ongoing struggle, one central arena of which was skilled workers’ contestation with F.W. Taylor’s “scientific management.”

He understood from his own investigations of the ante-bellum world of working-class formation how disruptive ethno-cultural divisions could be to the often-transitory periods of working-class mobilization. The gradual emergence of a system of wage labor from a diverse and unstable labor market in early cities provided for him the setting for class formation in the decades between the Revolution and the Civil War.

Montgomery’s appreciation of the powers of the state at all levels as an agent and ally of capitalist accumulation and its capacity to disrupt working-class mobilization through injunctions, labor market regulation, and outright military intervention helped establish a historical context for understanding the capacity of capital to reinvent itself in the face of workers’ determination to assert their interests. But, likewise, workers in the interwar years drew on their own traditions of organization and collective action and on new cultural currents to set the stage for and then defend an enhanced state that would represent the closest approximation of social democracy American workers might achieve.

How does what we called “the new labor history” still resonate in contemporary working-class history?

It is important for contemporary students of American working-class experience to grapple with the intellectual innovations that Montgomery brought to the field at a crucial moment of its reinvention. In some ways we take for granted the ideas that lay at the heart of the “new labor history” as it emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. The intellectual challenges we face today may be different, but some of the early pioneering work by Montgomery, Gutman, Brody and others, set crucial markers and established new understandings, that have guided us since, whether we realize it or not. In these essays, for instance, we would do well to revisit the worlds of ante-bellum Kensington, PA and the ethno-religious conflicts that shattered emergent class solidarities of the mid-1830s; or to grasp the excitement of rediscovering the Knights of Labor not as some backward-looking, anachronistic movement but as a vibrant social movement of a new working class that crossed traditional lines of skill, race and gender; or to consider the new, if fragile, alliances between skilled workers defending themselves against new “scientific” forms of management and unskilled factory workers seeking to stabilize their wages and the market for their labor. Like others—his contemporaries Hobsbawm, Perrot, Tilly—he asked us to consider more systematically the strikes and other forms of collective action workers undertook to defend their interests or on occasion to expand their rights but to do so by reconstructing the changing historical context of strikes and their impact.

Montgomery had a finely honed sense of historical change over time—in the structures of capitalism and in the forms of workers’ resistance. But he also understood in his bones that neither defeat nor success were permanent. He was impressed with the capacity of workers to invent new forms of struggle appropriate to their circumstances and likewise with the ability of capitalists to marshal their social and economic power to contain, at least for the time being, workers’ power.

What can we learn from his methodology?

Montgomery offered us a model for engaging the gritty realities of work on the shopfloor. He paid close attention to the details of work processes and the shifting power relations of the workplace—whether shaped by the aggressive role of shop stewards and a grievance process invented from below, or the codification of work rules that were the byproduct of collective action and negotiation. He was likewise a proponent of closely studying social relations in the community where the home, as both workplace and refuge, incubated and nurtured working-class identities grounded in distinctive class experience, far removed from the polite worlds of middle-class reform or the citadels of elite social power. In their dress, their language, the social relations of family life, and neighborhood sociability, workers cultivated a world of dignity and self-respect apart from the reigning norms of the dominant culture. Montgomery understood this world with an immediacy and a sympathy grounded not just in his scholarship but in his own work experience and the social bonds that he and Marty nurtured.

In sum, as a scholar whose originality provided conceptual guidance for the work of others in the field, as an astute book and journal editor, as a gifted mentor, and as an engaged scholar with a lasting connection to the worlds of organized workers and their politics, Montgomery remains a deeply influential presence in the field more than a decade after his passing.

We hope this collection of his essays will ignite new conversations about both David’s impact on the field and the evolution of the field itself.