Hello. My name is Dr. Michael Pierce, and I am a tenured professor of history at the University of Arkansas. My main research focus is the intersection of labor and race in this state. I am the author or editor of three books, most recently Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta. I was invited here as an expert on the nation’s first “right to work” law, which was enacted in Arkansas in 1944. Technically, Arkansas and Florida enacted “right to work” on the very same day, but historians emphasize the Arkansas measure because it became the model for similar laws enacted throughout the South in the 1940s and 1950s.

My thesis is simple—”right to work” was in no way intended to protect the rights of workers. But rather “right to work” was designed to: 1) keep Black workers powerless and relegated to the lowest paying jobs; 2) keep black and white workers divided and fighting each other for the benefit of employers; 3) promote white supremacy.

The best place to begin to understand the racist origins of “right to work” law is to look at the people who funded the 1944 campaign—cotton plantation owners throughout the Arkansas Delta but centered in Lee and Phillips Counties.[1]

Since the Civil War, planters in Lee and Phillips Counties had employed violence to keep the mostly black labor force working in peonage, a system that a Pulitzer Prize winning historian recently called “Slavery by another name.”[2]

On the two occasions when black workers tried to form unions to improve their conditions, planters responded with mass murder. In 1891, Lee County planters and their allies murdered about 20 men who went on strike to demand higher wages. This violence discouraged any union organizing in the region until 1919, when desperate sharecroppers and tenant farmers in nearby Phillips County formed another union. Planters responded by sending an armed posse to break up the union meeting, sparking an orgy of violence that saw somewhere between 200 and 400 black folks murdered. Called the Elaine Massacre, it is the largest outbreak of anti-worker violence in the nation’s history.[3]

I need to make this clear, the first “right to work” campaign was funded by the same planter class that had earlier employed mass murder to prevent Black workers from joining unions.

In the 1930s, though, Arkansas sharecroppers dared to form a new union—the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union. The fact that this union was biracial—both Black and white workers joined—discouraged the type of violence and murder that the planters had long relied on to keep unions at bay (it was one thing to kill black workers but quite another to kill white ones). Additionally, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union enlisted powerful allies in both the national labor movement that had embedded itself within the Democratic Party and an increasingly potent civil rights movement. These outside alliances also made it more difficult for Arkansas’s planter class to respond as it traditionally had—through violence and mass murder.

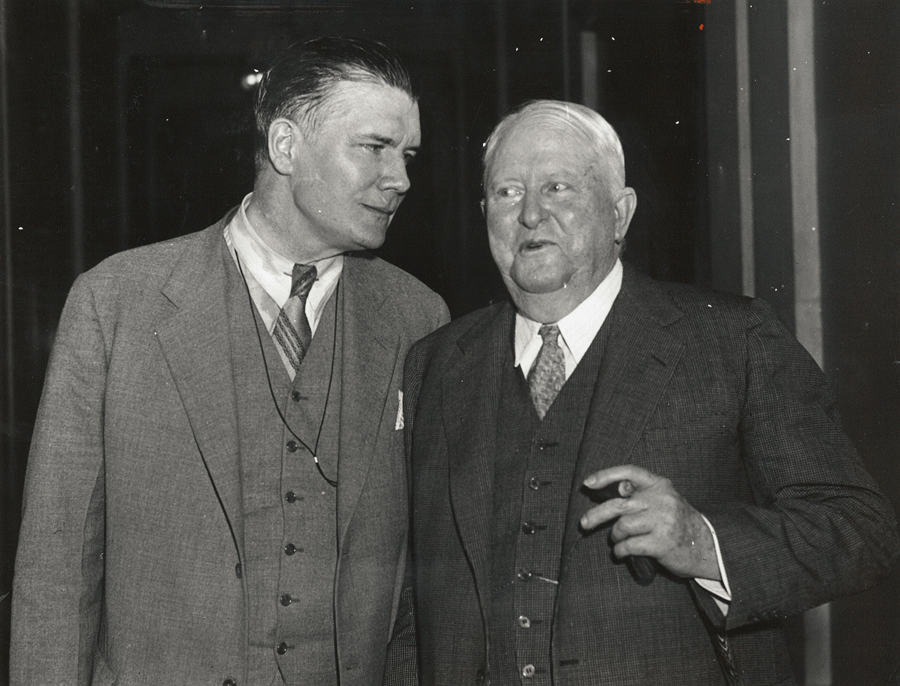

By the late 1930s/early 1940s, Arkansas planters—unable to resort to mass murder that they had long relied on—looked for new tools in their quest to destroy labor organizing. It is at this time that they turned to political operative Vance Muse and his Christian American Association to help them enact a series of laws, including the nation’s first “right to work” law, designed not only to make it as hard as possible for workers to join trade unions but also to prevent the type of biracialism found within the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union that threatened Jim Crow.

Muse had made a lucrative career lobbying for reactionary causes—against women’s suffrage, against a ban on child labor, against the 8-hour day for railroaders—often employing the most vile rhetoric. He was so loathsome that his own grandson described him as “a white supremacist, an anti-Semite, and a Communist-baiter, a man who beat on labor unions not on behalf of working people, as he said, but because he was paid to do so.”[4]

First, Arkansas planters funded Muse’s successful campaign to enact a state “anti-strike” measure that made all strikers (but not scabs or employers) criminally liable for any violence that occurred during a strike. Muse boasted that the law would “keep the color line drawn in our social affairs” and protect “the Southern Negro from communist propaganda.”[5] In effect, the “anti-strike” law gave legal sanction for strikebreakers to employ violence against union members.[6]

The next year, Delta planters funded Muse’s efforts to enact Arkansas’s “right to work” measure, an amendment to the state constitution. Muse warned that if the “right to work” measure failed, “white women and white men will be forced into organizations with black African apes … whom they will have to call ‘brother’ or lose their jobs.”[7] The planter-controlled Arkansas Farm Bureau later justified its support for the “right to work” amendment by citing organized labor’s threat to Jim Crow in the cotton fields.[8]

Shortly after Arkansas enacted “right to work,” Muse half-heartedly defended the measure in a national magazine against charges that it was racist and anti-Semitic: “They call me anti-Jew and anti-black. Listen, we like the n—-r—in his place. Our [“right to work”] amendment helps the n—-r; it does not discriminate against him. Good n—-rs, not those Communist n—-rs. Jews? Why some of my best friends are Jews. Good Jews.”[9]

In November 1944, Arkansas and Florida became the first states to enact “right to work” laws. In both states, few blacks could cast free ballots, elections were rigged by the powerful bosses, and political power was concentrated in the hands of an elite. “Right to work” laws sought to make it stay that way, to deprive the least powerful of a voice, and to make sure that workers remained divided along racial lines.

[1] The eminent political scientist V. O. Key called these Delta planters the “moving spirits” behind Arkansas’s right to work law; Southern Politics in State and Nation (New York: Knopf, 1949), 197.

[2] Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2008).

[3] William F. Holmes, “The Arkansas Cotton Pickers Strike of 1891 and the Demise of the Colored Farmers’ Alliance,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Summer 1973): 107–119; Matthew Hild, “Black Agricultural Labor Activism and White Oppression in the Arkansas Delta: The Cotton Pickers’ Strike of 1891,” in Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta: Essays to Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre, eds. Michael Pierce and Calvin White (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022), 13-28; Grif Stockley, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster, Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919 rev. ed. (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020) is the most comprehensive account of the Elaine Massacre.

[4] Vance Muse [III], “Making Peace with Grandfather,” Texas Monthly (February 1986): 116.

[5] Untitled Christian American Association pamphlet, reprinted in Fort Smith Union News, October 29, 1943.

[6] For an account of how this law was used both to excuse a strikebreaker who murdered a picketer and to convict those union members on picket duty when the murder occurred, see Daisy Bates, The Long Shadow of Little Rock: A Memoir (1962; reprint, Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986), 40-43.

[7] Stetson Kennedy, Southern Exposure (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1946), 84. Also see Fort Smith Union News, February 26, 1943.

[8] “Lastus with the Leastus,” Arkansas Farm Bureau Press, March 1945, p. 2

[9] Walter Davenport, “Savior From Texas,” Collier’s 116 (August 18, 1945): 82.