This is the final entry for a symposium on Steven High’s Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence, and Class (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022). The book tracks what High calls the “structural violence” and “social ruination” involved in the term deindustrialization. It traces the fate of Point Saint-Charles, a historically white working-class neighborhood and Little Burgundy, a multiracial neighborhood that is home to the city’s English-speaking Black community. We started with Lizabeth Cohen, who wrote an appreciation and posed questions. Next Austin McCoy offered reflections aimed at questions of activism and democracy. Then Ted Rutland probed the theoretical considerations that High deployed. Now we have a response to these entries from Stephen High. The symposium was organized by Ian Rocksborough-Smith, assistant professor of history at University of the Fraser Valley.

I want to thank Austin McCoy, Lizabeth Cohen and Ted Rutland for generously reviewing my new book and Ian Rocksborough-Smith for putting this symposium together for LaborOnline. The sightline of each reviewer reflects their intellectual interests and political investments. The same is true of course for my book.I find considerable inspiration in British sociologist Satnam Virdee’s appeal for us to challenge the deepening divergence of class and race analysis and recognize the intimate relationship between capitalism, class struggles, and racial inequality. Deindustrializing Montreal takes a comparative approach to Little Burgundy, one of the city’s first multiracial neighborhoods, and Point Saint-Charles, a historically white working-class neighborhood, which face each other across the Lachine Canal. Once the most heavily industrialized area in Canada, the two neighborhoods were emptied out first by suburbanization in the 1950s and 1960s and then by deindustrialization in the 1970s and 1980s. Over thirty years, the two neighbourhoods lost half of their population and those left behind were amongst the poorest in the city. State-led urban renewal and gentrification displaced thousands more.

Ted Rutland’s critique was in many ways expected. Anti-Black racism is foundational to our understanding of the structural violence of urban renewal in North America. It is the story that I expected to tell in chapter 4. What I found instead was a more nuanced story grounded in the particularities of Quebec. At its peak, Black Montrealers constituted 10% to 15% of the population of Little Burgundy but that was long before urban renewal. Many Black families had moved to newer neighborhoods in search of better housing. After all, 40%+ of the homes in the old neighborhood were still “cold flats” with no running hot water. A sizeable majority of those displaced by urban renewal were therefore white and francophone.

The social profile of the neighborhood mattered as Quebec was undergoing a political “Quiet Revolution” during these years. Quebec nationalists used the power of the provincial state to make French the language of work and to economically uplift working-class white francophones. The struggle was cast as one pitting English-speaking bosses and French-speaking workers – which did not leave much political room to recognize other forms of oppression. This nationalist impulse drove the government’s urban renewal efforts. The media thus universally spoke of the neighborhood as a poor white francophone district in need of immediate improvement. Of course, the invisibilization of Black Montrealers says much about the politics of Quebec nationalism and is, itself, a form of anti-Black racism. But this is not why the neighborhood was targeted for urban renewal unlike other North American cities.

The same could not be said about state-led gentrification in the 1980s. Urban renewal was a social experiment gone wrong, stigmatizing the area. In effect, the building of public housing transformed a white slum into a racial ghetto in the eyes of the media. To counter this, the state subsidized the conversion of adjoining railway and industrial lands into white middle-class housing. Early gentrification was therefore a direct result of anti-Black racism.

It is not a matter, as Ted Rutland suggests, of digging deeper until we find the expected story. As empirical researchers, we need to be open to the unexpected. That is one of the values of thinking about race and class together. But I do take Rutland’s secondary point that I could have engaged with Ruth Wilson Gilmore and more of the interdisciplinary scholarship on policing in a later chapter.

For his part, Austin McCoy’s comments focused on Point Saint-Charles and the politics of place-based activism in relation to the New Left. The neighborhood is home to many Quebec firsts: the first community health clinic; the first community legal clinic; the first housing cooperative; and the first community economic development corporation. Point Saint-Charles is therefore synonymous with neighborhood activism in Quebec. Over time, a comfortable narrative of “the activist neighborhood” has taken hold inhibiting harder questions being asked about the limits of place-based activism. In the book, I argue that the anti-statist politics of the communitarian New Left worked against neighborhood resistance against capital flight. Neighborhood factories therefore closed quietly without fuss. Community activists in the years since have largely accommodated gentrification and growing internal class divisions are effectively submerged in the idea of a single community interest.

As McCoy rightly notes, my argument leans on the idea that the communitarian anti-statist politics of the New Left insulated capital from this culture of resistance. McCoy suggests that I might have missed an opportunity to consider the ways that the anti-capitalist and anti-corporate current within the New Left might have led to a different politics. It is a point that I will take to heart in my next book on the ways the New Left shaped the generational Third Way social-democratic politics of the 1980s and 1990s. This period saw social-democratic parties, and the centrist US Democratic Party, pivot away from the redistributive politics of class to a post-materialist communitarianism and a consensual discourse around social partnership. It could well be that I am over-stating one current within the New Left.

Lizabeth Cohen’s great comments, in turn, got me thinking about the ways that oral history writing differs from more standard academic writing. People’s stories are woven throughout Deindustrializing Montreal, offering readers an embedded sense of how these sweeping changes were experienced, understood and now remembered. This layering process is necessarily less linear than most scholarly writing. But these stories are essential if we are to truly understand the full meaning of dis-place–ment. I see the book as being a history from the bottom-up and the inside-out.

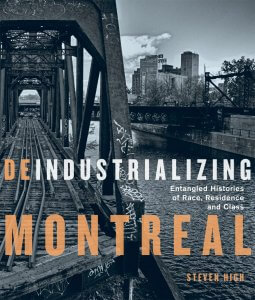

Oral history writing can also differ in tone and authorial voice. My writing style has become more informal than most historians, as I have sought to find middle-ground between the vernacular spoken by my working-class interviewees and that expected in academic analysis. I like to think that there is a reflexive space in-between the two that works for academic and popular audiences. Certainly, the book was written for both audiences. Thanks to McGill-Queen’s University Press, the book’s 205 photographs – a few of which are reproduced here — also act to bridge residents into the academic text and readers from outside the city into these two neighborhoods.

Lizabeth Cohen does express some discomfort at my taking sides. She writes “what I think is sometimes missing is a more even-handed discussion of what other options decision-makers might have had.” Cohen refers specifically to my critique of the dominant discourse of “social mixité” in housing policy as an example of one-sidedness. In this, I disagree. Just as meritocratic thinking has provided ideological cover for the structural violence of capitalism, the idea of social mix serves to legitimate gentrification in the name of breaking up pockets of poverty in order to prevent a “culture of poverty” from taking hold. In both cases, the poor are blamed for being poor. As I argue in the book, the best working-class defense against residential displacement is social housing (cooperative, non-profit and public housing), and a lot of it, or still active industrial sites located nearby.

That said, I think Cohen’s point is an important one. In these polarized times, it is essential that we listen across political difference to better understand the politics of our time. My purpose in writing the book was not to judge but to understand. Readers therefore encounter the life stories of gentrifiers as well as long-time residents. But I don’t soften my analysis in doing so.