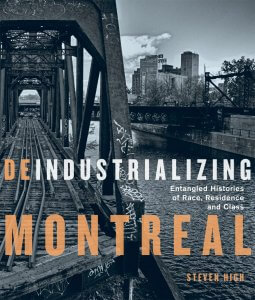

This is the second entry for a symposium on Steven High’s Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence, and Class (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022). The book tracks what High calls the “structural violence” and “social ruination” involved in the term deindustrialization. It traces the fate of Point Saint-Charles, a historically white working-class neighborhood and Little Burgundy, a multiracial neighborhood that is home to the city’s English-speaking Black community. Yesterday, Lizabeth Cohen wrote an appreciation and posed questions. Today Austin McCoy offers reflections aimed at questions of activism and democracy. We follow up with Ted Rutland, and a response by author Steven High. The symposium was organized by Ian Rocksborough-Smith, assistant professor of history at University of the Fraser Valley.

In his landmark book, Deindustrializing Montreal, Entangled Histories of Race, Residence and Class, historian Steven High poses the central question for scholars of labor and neighborhood and economic change have asked about the rash of plant closings in the 1970s and 1980s—why was there not more mass protests against factory shutdowns in hard hit neighborhoods such as Point Saint-Charles?

High addresses this question by contextualizing workers’, unions’, residents’, and the state’s responses to economic restructuring in a broader context of neighborhood change, economic transition, and social and cultural practices of residents living in two Montreal neighborhoods—Point Saint-Charles and Little Burgundy. In his sweeping narrative, High complicates understandings of deindustrialization by enlarging the approach beyond an urban, or metropolitan, history framework and adopting an interdisciplinary method bringing multiple subfields of history into conversation including geography, culture, labor, policing, youth studies, and racial capitalism. And while it may appear that High is narrowing his focus by concentrating his study on two neighborhoods, Deindustrializing Montreal addresses issues of national and international importance including Canadians’ attempts to manage economic and residential transition as well as the multinational character of Black political organizing in the labor and Black Power movements.

High grounds his analysis of economic restructuring within a longer narrative focusing less on the decline of a particular city and more on Point Saint-Charles’s and Little Burgundy’s transition into a post-industrial space. This raises questions about how scholars have approached deindustrialization and the question about muted collective resistance to plant closures. While High acknowledges that the urban crisis frame helps explain how political officials could write off neighborhoods like the South Bronx or Little Burgundy and “render visible the actions of the modernizing state and white middle-class gentrifiers,” he argues that this approach also tends to deemphasize capitalists who also help engineer what geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “organized abandonment” of racialized neighborhoods. Consequently, in addition to the suburbanization of unionized labor forces, which also occurred in U.S. metropolitan areas, High contends one is less likely to see the emergence of widespread protests against deindustrialization in cities that are able to manage transitions due to possessing a more diverse economy. Ultimately, where laborers worked and lived might help explain some workers’ responses.

While deindustrialization did not spur massive opposition in communities such as Point Saint-Charles, High locates notable citizen and labor union resistance to plant closure in that neighborhood in the late 1980s. And while the neighborhood was known for its activism, opponents of plant closure appeared to adopt a limited outlook in their fight against job loss. “There were isolated voices who argued that activists should see workplace and neighbourhood struggles as one fight against capitalism,” High writes. “But, by and large, the popular and union struggles remained separate” (High, 250). Thus, advocates for social housing and for saving jobs organized on parallel tracks despite the fact that deindustrialization created the conditions for planners and policymakers to enact a post-industrial vision of development in Point Saint-Charles that encouraged accepting plant closings and economic transition and enabling gentrification (High, 258). Yet, despite these conditions, oral interviews of activists illustrated the emergence of a myth of Point Saint-Charles symbolizing an “activist neighborhood” where one could find legacies of “effective organizing” grounded in political approaches such as Alinskyian understandings of community organizing and advocacy work of the Christian Left that would later mask intellectual and strategic shortcomings.

The separation of struggles for social housing and against plant closure produced a contradiction within the image of Point Saint-Charles as an activist neighborhood. High states, “While most neighborhood activists in Point Saint-Charles were focused on housing issues during the 1970s and 1980s, the area’s mills and factories continued to close. As far as I can tell, there were no angry pickets or sit-ins when Northern Electric shuttered its massive Shearer Street factory in 1973…This inaction is all the more striking given the neighbourhood’s activist reputation” (High, 264). One reason for this inaction, according to High, was the influence of New Left’s anti-statist politics. As High asserts, activists viewed the state as their primary obstacle to defending the neighborhood while private capital pulled the rug from beneath the community.

While New Left anti-statist thought might explain activists’ inability to build a politics that addressed both state and corporate power in PointSaint-Charles in the 1980s, we might be missing an opportunity to draw a sharper contrast between this New Left anti-statist and an anti-capitalist, or anti-corporate approach that arose in the U.S during the 1970s. Many U.S.-based New Leftists turned towards a fight against deindustrialization and corporate power in the Midwest during this period. High reminds readers that U.S.-based analysts of deindustrialization often pointed to absentee owners as major culprits of capital divestment. However, New Left activists and intellectuals such as Tom Hayden began calling for “economic democracy” during the 1970s. Economic democracy in this period referred to a rehabilitation of a constellation of democratic values, policies, and economic experiments such as community, worker, and municipal ownership of industrial property and public control over banks and utilities.

In addition to calls to further democratize the economy during this period, U.S.-based New Left descendant groups such as the Ohio Public Interest Campaign also blamed deindustrialization on the growing power of multinational corporations. One of the main problems for OPIC, however, was their inability to articulate broader goals to match their larger progressive vision that included adopting a public financial sector (community ownership of banks, insurance companies, and development corporations), policies encouraging full employment, and labor law reform. Instead, they focused on building a campaign to enact a state-based anti-plant closure law. Their analysis of the political situation in the 1970s explains the moderation of their goals. OPIC recognized that a major source of political power—organized labor—entered a period of retreat amid a business offensive, a conservative resurgence, and the emergence of neoliberal governance.

High’s critique of Point Saint-Charles as an activist community culminates with a discussion of movement memory in relation to the construction of a community mural depicting mass protest as the neighborhood moved from the industrial era of the 20st century to the post-industrial one in the 21st century. However, when set against High’s analysis of defeats and the emergence of gentrification, and a few of the critics of the neighborhood’s myth, he argues that maybe there is little to celebrate. “The transition to our post-industrial present is depicted as a liberatory moment and one to celebrate…I’m not sure if most long-time residents would agree with this enthusiastic assessment” (High, 284).

High raises an important question with his discussion of the mural—Who within the community gets to frame and tell stories of organizing, activism, and protests? High’s analysis of the mural prompt further questions—who exactly produced the mural? Why was it commissioned? Was there any community feedback in its planning, or how did residents respond? What are the motivations behind maintaining this myth? As Tom Hayden contends in The Long Sixties: From 1960 to Barack Obama, debates and battles “over memory, monuments, and museums,” or the legacy of social movements represent a key phase, even after the activists and organizations are long gone. And, in High’s analysis, these debates are not just between those who occupy powerful position and activists and residents, sometimes battles over how people should understand social movements and their outcomes are fought among activists and within communities, themselves.

High’s critique of the community frame of organizing against capital flight echoes labor historians’ critiques of responses to plant closure. Jefferson Cowie’s analysis of community in Capital Moves: RCA’s Seventy-Year Quest for Cheap Labor argues that it was necessary for U.S. workers to find ways to circumvent economic nationalism in favor of a global outlook and internationalist strategy. However, as Cowie, High, and other scholars of deindustrialization have illustrated, U.S. workers’ inability to organize across regional and national boundaries, while multinational corporations command operations across scale, highlights the longstanding problem for unionists and communities—the privileging of the private sector’s private property rights over those of workers and residents.

Consequently, this problem, as High underscores in Deindustrializing Montreal, raises questions about the prospects of democratizing property ownership and control, and economic relations, generally. Many on the left in and outside of academia have devised, advocated for, and in rare cases have implemented alternative visions for “just cities” and economic forms. (The Cleveland-based Evergreen cooperative is one such example.) Yet, usually these alternative visions, tactics, and strategies, such as participatory budgeting and worker-ownership of businesses, remain intensely local and are difficult to scale up without a national base of political power.

Steven High’s insightful critiques of the community frame in Deindustrializing Montreal reveals the tensions between the search for a usable past and the imperative to develop a more complex understanding of deindustrialization, race, class, politics, and place. As historians such as Robin Kelley proclaim—even if movements do not achieve their stated ends, they still produce “freedom dreams”—innovative ideas, analyses, tactics, and strategies for future struggles. Yet, High’s text reminds us that complex and multidisciplinary approaches can offer the necessary clarity for scholars, activists, and those interested in histories of deindustrialization. Communities and movements can give themselves the best chance at responding to racial capitalism by combining transformative activism with a clear-eyed analysis. Ultimately, Deindustrializing Montreal, in all of its interdisciplinarity and its marshalling of an astounding array of sources, offers historians and general readers with a dynamic blueprint for understanding long histories of neighborhood, economic, and racial change.

67 Comments

Comments are closed.