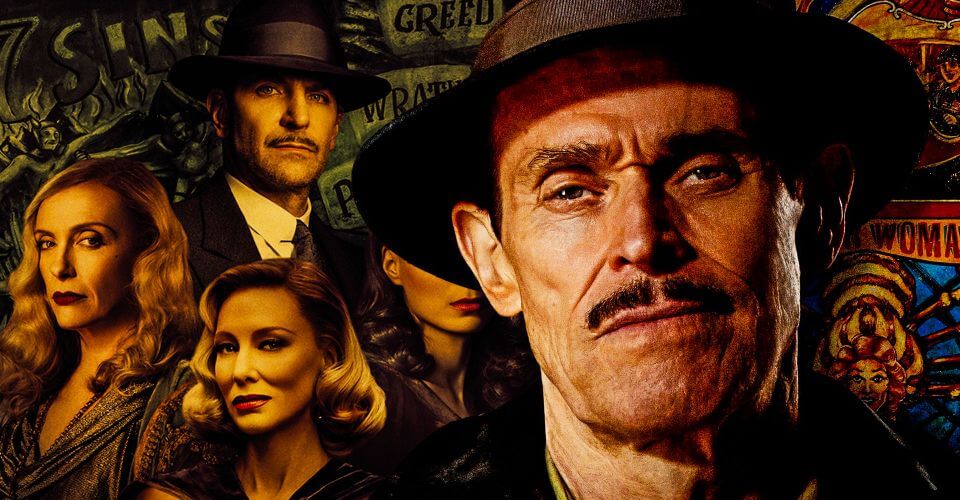

At the 2022 Oscars, Guillermo del Toro’s remake of Nightmare Alley could win four awards for its portrayal of life in a Great Depression-era carnival. The story follows Stan, played by Bradley Cooper, as he moves between stages and jobs in the traveling entertainment industry. In many ways, the movie characterizes the life of a carnival worker by offering only fleeting glimpses into the life of Stan, who is haunted by his past. But the film also offers deeper insight into the real labor of traveling entertainment during the Great Depression.

The first few scenes of the movie encapsulate just how precarious the work could be. Stan attempts to get hired with the show during a stint of bad weather. A rainstorm meant that more work had to be done and with more hands, and we witness Stan’s bartering his way into the pay ledger. In a real-life example, the Cole Brothers Circus ran into storms during a Saturday night snow in late July of the 1937 season. They announced the impending weather to the sold-out crowd, although most of them stayed to watch the remainder of the show. When the storm hit just after the show ended it caused substantial damage, leaving workers to clean up the debris that night and sew the canvas during a cancelled performance the next day.

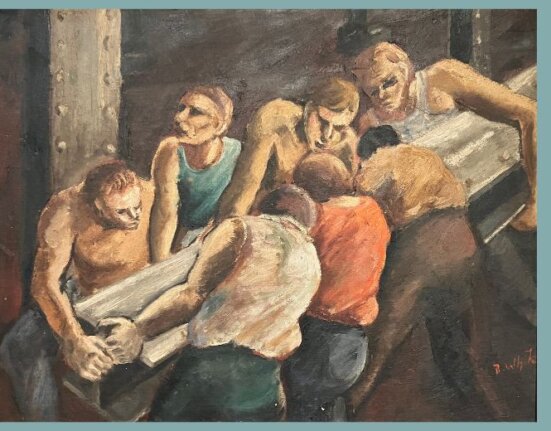

Workers often demonstrated their allegiance to their employer, their colleagues, and the larger circus world. Al Priddy worked was a circus trooper with several larger outfits, including the Ringling Brothers and Al G. Barnes shows. In 1930, he spoke on the need for circus workers to think about the common good. He noted that “You will nowhere find a class of people who are more loyal to themselves, to their fellow workers, to their employer, to their calling than are those same circus people.”[1] As Priddy noted, the work, and even the pay, could be unpredictable, but workers often acted with deep allegiance to their employers that fed and kept them. Nightmare Alley offers some similar sentiments. The workers in the movie band together, especially in the face of regulation. As police officers threaten to shut down the show, Stan swoops in with a mentalist con that appears to lend legitimacy to the show. His skills as a mentalist, which he hones throughout the course of the movie, also demonstrate the ways that workers understood their relationship to one another. Jobs in traveling shows were highly skilled. Whether assembling the tent, caring for the menagerie animals, or performing in the sideshow, workers held unique skillsets that they gained through apprenticeships and on-the-job training.[2]

As Stan demonstrates, tented shows relied on humbug.[3] Stan’s work makes him a con artist, which was something management and workers found financially advantageous. As he becomes more skilled at the act, he convinces audiences that he has uncanny abilities to convene with the dead in spook shows. Stan’s mentalist performance in the carnival was not the only con in the show. As the manager notes early in the movie, the sideshow geek could only be recruited from a population of otherwise hopeless alcoholics who would became dependent on their gruesome job in exchange for booze. The narrative resembles the true story of other sideshow workers billed as cannibals and financially exploited, like George and Willie Muse.[4]

As the narrative shifts to a different time and space, viewers see Stan working a room as a mentalist. During this time in particular, Stan learns how to interact with audiences in a way that demonstrates part of what made traveling entertainment experiences so memorable for people. It was a democratic amusement that invited audience participation. Maybe the nature of public-facing tented show work is best distilled in Stan’s line to Dr. Lilith Ritter when she insinuates that he might break character. “I’m always on, doctor,” he says. That sentiment of working a job that did not offer time off is one that traveling entertainment workers of nearly every job category expressed throughout the season. Workers could get privacy from the public eye as shows moved between cities on the railroad, but when shows were parked and the lot was assembled, they were always performing. People who bought tickets or curious journalists who knew that behind-the-scenes stories were a public favorite watched as workers set up the lot, sewed costumes, and even cared for their children.

As Stan’s career and life quickly unraveled, he returned to the world of traveling tented shows. Although he had reached some notoriety and wealth through his act, he accepted what was arguably the lowliest job in the show. This trajectory from unemployed to famous and then back to a completely dependent on the tented shows sheds some light on lived experiences of real workers. Everyday workers who were brave or talented enough to jump in a tiger cage or somersault on a horse could end up on a circus poster and with an impressive contract for the season. But that work was often short-lived. Acts staled as management constantly advertised for “never-before-seen” performances, leaving performers constantly trying to remain relevant. As Nightmare Alley shows, and as every Depression-era traveling tented entertainment worker knew, lines between manual worker, uncontracted sideshow workers, and high-paid star were nearly nonexistent.

[1] Al Priddy, “The Way of the Circus: With Man and Animal,”(Chicago, The Platform World): 19, The American Circus Collection, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 1, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[2] For the most recent treatment of circus labor and union organizing, see Andrea Ringer’s forthcoming book Circus World: Transnational Labor and Performance to be published by the University of Illinois Press.

[3] For a deeper analysis of one of P.T. Barnum’s most famous hoaxes, see: Benjamin Reiss, The Showman and the Slave: Race, Death, and Memory in Barnum’s America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001).

[4] Beth Macy, Truevine: Two Brothers, a Kidnapping, and a Mother’s Quest: A True Story of the Jim Crow South (New York: Little, Brown & Company, 2016).