“Freedom” is a fickle force, especially when it is expressed in the guise of aggressive flag-waving nationalism. Recent convoys in Canada and the U.S. have claimed the word to define themselves as they descended on their nation’s capital cities in recent weeks. The disruptions in Canada were significant, as Ottawa was nearly shut down for weeks while the biggest commercial thoroughfare at the Ambassador Bridge between the U.S. and Canada (Detroit, MI and Windsor, ON) also faced shutdowns.

Many commentators in Canada and the U.S. have noted the connections between these so-called “trucker” protests and far-right extremists, certainly in terms of who organized and initiated these actions – which mirrored the worst of the January 6, 2021 riots in Washington, D.C. Most of the organizers of these events are not themselves representative of truckers, their unions, or their industry. Rather, they tended to represent far-right political organizations who wish to use Canadian, American, Libertarian, and even Nazi flags as representative emblems – many of them with conspiratorial understandings of medical science, public health, and democratic political processes in liberal democracies.

To say they do not represent a majority of workers who currently drive ‘big rigs’ across the continent and keep the majority of us fed and materially supplied during this awful pandemic would be an understatement. As Manan Gupta, publisher of Road Today, a magazine that represents South Asian Canadian truckers indicates, “There is a vocal minority, which is trying to steal the headlines, but a silent majority has actually been working day and night.” About a third of Canada’s roughly 180,000 tractor-trailer drivers are immigrants, according to the most recent survey, in 2016. Indeed, the implicit and explicit racism of these protests has led some South Asian Canadian truckers to consider other occupations. Moreover, Mexican truckers seem more than willing to abide by vaccine mandates during this ongoing public health crisis – a likely consensus among most North American truckers today.

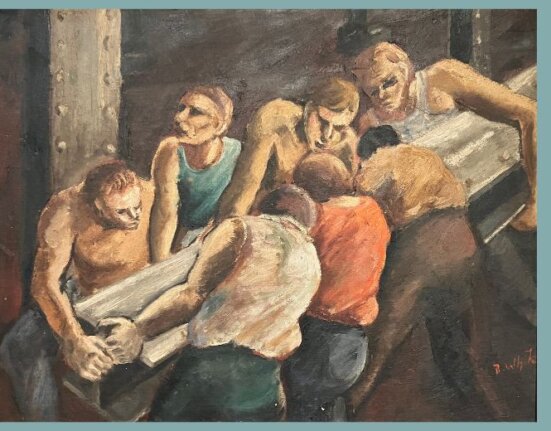

Truckers have not always been part of this fringe minority causing unrest over vaccine mandates nor symbolic engagement in far-right populist movements with obvious racist undercurrents. Bryan Palmer’s book profiles the connections between truckers, teamsters, and the radical left in Minneapolis in 1934 during that city’s influential General Strike. Considering that era of working class upsurge and influence is instructive. Palmer’s work suggests truckers served a radical and revolutionary vanguard role in working class solidarity across sectors and identities. Moreover, as he notes, “[f]ar more than merely sectional struggles of one particular industry, the truckers’ strikes of 1934 were explosive working-class initiatives that galvanised the entire spectrum of Minneapolis labour – skilled and unskilled, unemployed and waged, craft-unionist and unorganized, male and female – and polarised the city in opposing class-camps. As a result of this trio of workplace-actions in 1934, working conditions in the trucking industry improved, wage-levels were raised and trade-union recognition was secured.” Such a movement seems impossible in today’s climate of accentuated culture wars and animosities and weakened unions. Yet a truly representative working-class movement of truckers, given their strategic role in transporting goods and commodities, might actually speak to the core inequities of these times and shift protest in a direction to contest rather than enforce power structures. (See also Bryan Palmer’s Labor Online Post)

James Menzies wrote for Trucknews.com regarding the recent convoy movement: “I feel bad for the truckers who thought this was about them. It never was. There was never any discussion around the real issues you face every day. Lack of safe parking. Poor road conditions. Access to clean restrooms. Unpaid detention time at shippers and receivers.” Indeed, the poor working conditions of all truckers across North America, worsened during the pandemic. But it has been exacerbated by automation and threats to their lives and livelihoods. These issues were never at the center of these so-called trucker protests. Rather, these events are part of the far rights’ attempts to co-opt public attention and resources to galvanize a mercurial base of voters for upcoming congressional and federal elections across the 49th Parallel.

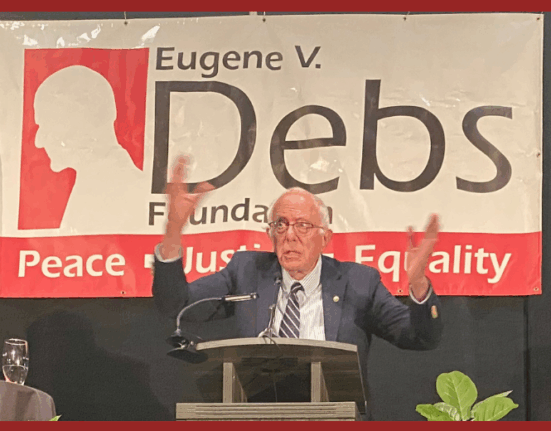

It remains to be seen whether a more diverse constituency of truckers might join the ranks of more resistant and representative multi-racial working-class formations in North America at present demanding accountability and equity. As it stands, it seems the far-right is doing its best to co-opt these quintessential symbols of the continent’s capitalist ventures for the edification of populist right wing icons and constituents.

A more representative multi-racial working class has actually promoted public health measures and simultaneously kept us fed, working tirelessly and selflessly to deliver goods and groceries across the vastness of North American landscapes. Surely, such labors deserve the dignity, security, and affirmation of an unthreatened livelihood for being essential workers in these times.