Bob Rossi is a long-time member of the Slovenska Narodna Podporna Jednota, (SNPJ) who has interviewed and corresponded with dozens of SNPJ members in writing a history of the 1920s coalfield culture and union battles. This post is derived from a presentation he gave to SNPJ Lodge #371 in Cle Elum, Washington in September. -Editor

As I have done my research on Colorado coal mining communities in the 1920s and pieced together an account of the 1927-28 Colorado mine workers strike, I have discovered that in order to understand these communities and that strike we need to understand how the churches, lodges, and early unions in the coalfields functioned, and how workers’ struggles for control of their work and workplaces were joined to their communities through these institutions.

Churches, lodges, and unions were important to the creation of civil society in the Rocky Mountain mining west. Their memberships often overlapped in western mining communities and gave expression to class and ethnic consciousness as these developed.

There were scores of lodges, fraternal organizations, death and benefit societies, church-related guilds and societies, and insurance organizations present in the Colorado coal fields from the 1870s into the 1940s or 1950s. Some were exclusive, masculinist, and racist. The Improved Order of Red Men, many of the various Masonic orders, and the Ancient Order of United Workmen (AOUW) fit into these categories, at least on a local level. There were African American organizations, such as The Sisters of the Mysterious Ten and the United Brotherhood, that had particular staying power, and the Sociedad Protección Mutua de Trabajadores Unidos that united Hispano, Mexican, and Mexican American farmers and workers.

There are also examples of people of color and whites joining together in insurance societies, sometimes under Black leadership, and of Native Americans and whites cooperating in the pro-labor Independent Order of Foresters. The Ladies Catholic Benevolent Association gave women hands-on experience in managing insurance and mutual aid funds and support systems in Colorado’s industrial regions. We also have the lodges and benefit societies that were created by the “new immigrants” of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that were often, though not always, ethnically or nationally specific.

Many of these organizations functioned at one time or another as proto-unions to the extent that they provided benefits and insurance for mine workers and their families, supported members when they went on strike, and assisted transient or itinerant mine workers as they searched for work. Some went further and gave voice to workers and demands and were associated with newspapers that publicly shamed scabs.

I argue in my presentations and writing that many of these organizations taught workers and their family members basic democratic principles and how to function as activists and that they were effectively calling strikes over workplace safety when they required members to leave work and attend the funerals of lodge members who were killed at work.

The Slovene National Benefit Society (Slovenska Narodna Podporna Jednota, SNPJ) formed in 1904 in order to provide life insurance and disability benefits to Slovenians in the United States. Researchers and SNPJ members tend to think of the SNPJ as originating in the industrial Midwest and eastern cities. My research has taken up the existence of the SNPJ in the western mining states, and I argue that the lodge’s origins are there in part and that the SNPJ formed from working-class militancy. The SNPJ came into being as turn-of-the century strike waves in western coal and hardrock mining continued movements that had begun in the 1890s. SNPJ lodges existed in most prominent western mining communities.

The SNPJ supported strikers during the Industrial Workers of the Word (IWW)-led 1927-28 Colorado mine workers’ strike, and refused to provide benefits to members who crossed picket lines there and elsewhere. It would be hard to understate how much the coal companies hated the SNPJ. It was believed that mine workers who joined IWW and struck in 1927-28 in Colorado could not receive Catholic funerals if they died without repenting. The SNPJ and other lodges commonly assigned lodge members to remain with the body of a deceased member in their home for two days before a funeral and to parade at the member’s funeral.

The Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron company (CF&I) was so suspicious of the SNPJ by 1927 that it interfered with an SNPJ member’s funeral in Crested Butte and ensured that the Slovenian and Croatian lodges there never again had a processional at their member’s funerals. Pressure was probably brought to bear on clergy in Crested Butte, and lodge leaders were probably informed that processions would not be welcome in the town. Records at the CF&I archives in Pueblo, Colorado indicate that the company was alarmed by the presence of the lodges, and the SNPJ in particular, and covertly investigated these organizations.

Researchers and SNPJ members often think of the SNPJ as having been a Slovenian organization until intermarriage changed the nature of Slovenian American families and communities, but I maintain that this must be qualified. First, the SNPJ included people in its early years who might be better described as Austro-Slavs, Austro-Slovenes, and Austro-Italians than as Slovenians. The lodge was in many ways an Austrian, Northern Italian, and Croatian organization as well as being a Slovenian organization in its early days.

The work of setting up and running an insurance society that could withstand precarious economic conditions and pay out benefits during plagues, floods and fires, strikes, and industrial disasters had to be taught, and the early SNPJ leaders learned how to do this from the AOUW and a Czech-Bohemian lodge. The Delagua mine explosion in 1910 killed 79 mine workers, 26 of whom came from Yugoslavia, and providing for their burials and for their families strained the SNPJ’s finances.

The Cherry, Illinois mine disaster took the lives of 20 SNPJ members and led the SNPJ to assess its members to help the victims of these disasters and their families. The lodge supported the mine strikes of Colorado 1910 and 1913 and 1914 and gave financial aid to Slovenians in Cle Elum when a fire destroyed much of their town in 1918, before a lodge was formed there. The flu epidemic of 1918 cost the SNPJ more than $135,000 in benefits (well over four million dollars in today’s money).

Slovenian workers and working-class intellectuals in the western mining states practiced a form of Slovenstvo, or the way of being and feeling Slovenian, that was not entirely exclusivist and that complemented, rather than negated, the formation of a common cultural context that united significant numbers of Slovenian, Mexican and Mexican American, and Italian and Italian American mine workers in Colorado from around the turn of the century into the 1930s.

Similar trends were evident among members of the Polish National Alliance and certain Italian lodges in the southern Colorado coal fields prior to the Ludlow Massacre of 1914. The Slovenian intellectual Louis Adamic later raised the concept of Sloventsvo to a universal democratic-humanist principle. I have been inspired by John P. Enyeart’s new work on Adamic.

We see this taking shape in Pueblo, Colorado in 1901, when Martin Konda established Glas svobode (The Voice of Freedom) with Ivan Medica and others. This secular newspaper and other radical Slovenian efforts, including the Slovene Free-thinking Benefit Federation and Proletarec, laid the basis for the modern Prosveta newspaper, still published by the SNPJ. This early press was known for its radical positions, but some of these newspapers also published classical literature. Colorado had at least 8 Slovenian newspapers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

On the other side in Pueblo was Fr. Cyril Zupan and the Slovenian Catholic organizations who bitterly opposed Konda and the SNPJ and the other groups. Slovenstvo could be defined and applied by conservatives as well as by radicals. Fr. Zupan had a Slovenian housing subdivision in Pueblo built as a public works project and named after him. Pueblo is the only town that I know of where the term “Bojohn” is used to describe Slovenians, and perhaps others with roots in eastern Europe and the Balkans. Slovenes were also referred to as “Granish” in many mining and steel towns.

Western states mine workers were often transient or itinerant from the 1880s to the 1930s. If they were hardrock or metal miners, they may have moved from as far south as Mexico or Arizona north to New Mexico and Colorado, then into Utah, and then into Montana, and sometimes into Canada or Alaska, and then to South Dakota, and perhaps back to Colorado and south again. If they were coal miners, it was common to move from Kansas and New Mexico to Colorado, then to Wyoming and Utah, go north to Washington, east to Montana, and south again. Mine workers also arrived in the western states after working in Pennsylvania, Illinois, Arkansas, and Oklahoma.

Lodges provided contacts and news of where work was available along the way, and for SNPJ members there was also the comfort of hearing Slovenian spoken and participating in Slovenian communal life as they travelled. There is record of men wearing an SNPJ badge as they travelled by freight train because identifying as an SNPJ member sometimes helped them on the trains and in the hobo jungles. These workers had a Slovenian identity, an identity as mine workers, and identities as transients or itinerants.

Given the SNPJ’s support for these workers and its support for unionism and fraternalism, these workers must have carried with them news from the coalfields they worked in and the lessons that they were learning from the lodges and the mine workers unions. Tavern owners and bartenders became central to the Slovenian immigrant experience in the western coalfields because they functioned as bankers and directed workers to boarding houses and employment opportunities. A tavern, or gostilna, and a small area around it in Oak Creek, Colorado was designed on the Slovenian-Bosnian model. During the years of the Great Depression many Slovenians and others left the western coalfields and went to California, St. Louis, Detroit, and Chicago, and some apparently took traditions of mine worker unionism and the SNPJ with them and helped build unions and lodges in their new locales.

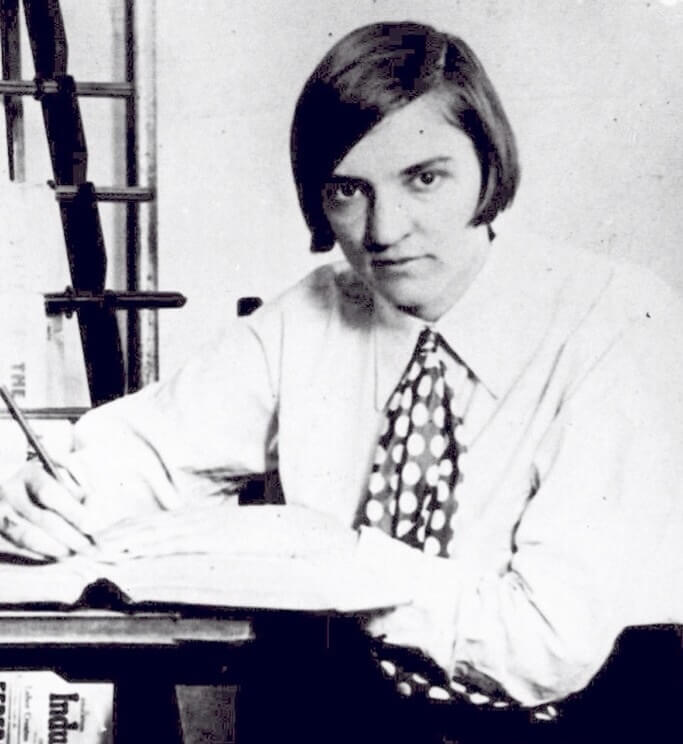

Alex Howat—Kansas UMWA leader and popular union dissident., from Wikipedia.

Kansas is important to this story. Mary Pistotnik grew up in a coal camp in southeastern Kansas and went to work at twelve years of age and found a position in the miners’ cooperative store at fourteen. She worked outside of the home until she was married and became a leader of the SNPJ. She supported the militant Kansas union leader Alexander Howat and was active in the mine workers strike of 1921 “(I) also marched with women in 1921,” she told me. “I was only 19 and married and lived in Franklin. It was scary for me, especially when the militia moved in.”

Ms. Pistotnik explained her involvement by writing:

(H)ow did I get involved in Howat & the miners struggles—Why? I was a Coal miners daughter & that’s all we knew, that all the whole Breezy Hill world talked about—We lived way out in the country, . . . had to walk to school in all kinds of weather—Breezy Hill population almost 3,000 all nationalities—We all got along. . . I quit school—as I had a job in a home…My mother cried. & I said my girlfriend works there & I need shoes, so I took the job the job then at age 14½ the cooperative store board members voted for me to work for them in the store. I was the happiest girl in the world….I didn’t have much schooling but as practical experience along the way thru life I learned a whole lot…Talk about strikes we had them one after another—& Alec Howat would speak at parks. Thousands of people would listen & they put him in jail more than once but Alex did not give up…Talk about strikes—some time one wonders how we survived but you have to give to the people that came here from old country they brought their culture with them they knew how make a living—We never was hungry or cold…I often think how brave they were—no money strange country….About Alex Howat…he stopped by my place had a beer and lunch many times. He was very intelligent person very much liked by the people.” Ms. Pistotnik’s experience in the cooperative store was copied by Slovenes living in Colorado’s Trinidad mining region in the teens and by Slovenian women who founded a cooperative laundry there in the 1930s.

This is one of many letters that I have received, and I find our people speak with poetry.

Regarding strikes, Pistotnik remembered that “we had them one after another”, and Alex Howat would speak at parks. Thousands of people would listen, and they put him in jail more than once but Alex did not give up. . . .some time one wonders how we survived but you have to give to the people that came here from old country–they brought their culture with them. They knew how make a living. We never was hungry or cold. . . .I often think how brave they were—no money strange country.

Anna O’Korn, also Slovenian and living in a Kansas coal camp, recalled that when strikebreakers arrived in her community in 1919, a decision was made that men would stay home and do the housework while women would march and protest. A woman who spoke English gave orders to the women who did not. The women walked or hitched rides on trucks or took trollies to get to the mines, and they appealed to the strikebreakers not to help break the strike; some men consented, but others did not. “We all went over to see if we could do some damage,” she said. There was a confrontation between the women and the militia, and some women claimed that the militia fired shots.

Mary Pistotnik and Anna O’Korn lived in an environment that was described for me by one-time mine worker John Novak, a Slovenian, of Augusta, Kansas in this way: “Most of the miners where from Austria, Yugoslavia, Germany, France and Italy, and a few English. Before I went into the mines most of the miners lived in company houses and they had company store where you got most everything you needed. And most little town had a dance Hall where they had dances on weekends. Later in years most of the miners bought these…homes. And had… gardens, chickens. Some had a cow or two a few had hogs and so forth. . .Some would work on a farm during the harvesting time…Most of the Slovenians belonged to the SNPJ and there was also a SSPZ lodge (Slovene Progressive Benefit Society)…they all ways had a Meeting on Sunday once a Month where you paid your dues and they had dances. And out door picknick in the Summer time….Most every body there were strong union men…”.

Howat was taken as a hero by many Slovenian mine workers. He was said to have supported and defended immigrant mine workers, including Slovenians. One story that I heard from mine workers had to do with a coal company that allegedly put a young Slovenian man on a job running a steam shovel in a strip mine and that miners objected to strip mining. The young man did not know the work. Howat and other union leaders supposedly called illegal protest strikes in order to resolve the situation, and when Howat was sent to prison the mine workers told the judge that they would strike for every day that Howat was locked up. I have not found any evidence that this occurred, but the myth of Howat’s militancy and effectiveness as a leader was still in place in Kansas when I began my research in 1982.

Slovenian mine workers also gave support to Robert Harlan, who challenged John L. Lewis for the presidency of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) in 1920. Howat and Harlan both had bases of support in the western mining regions, and they and insurgent movements and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) irked Lewis and UMWA officials in the western states through the 1930s. The Slovenian community in the Cle Elum, Washington mining region divided over the matter of a Left-influenced breakaway mine workers union that had some Slovenian American local leadership in the early and mid-1930s.