On June 17, 2025, an official Illinois historical marker that highlights the experiences and activism of Black coal miners in Illinois was dedicated at the Springfield Transportation Hub, on the southwest corner of 11th and Washington streets in Springfield, Illinois. This new addition to the state capital’s memorial culture stands near the more well-known 1908 Springfield Race Riot National Monument.

Titled “Henry Stephens, 1869-1939”, the marker recounts the efforts of Stephens and African American miners in Illinois to build equal opportunity in the North in the Jim Crow era. I have been researching Stephens as part of a wider project on a book on the Illinois Mine Wars, 1860-1940, and his story is even more fascinating than what appears on the marker. Erecting the marker was a collective effort, and all involved felt proud to have contributed to memorializing an unsung activist. As people walked by at the dedication, they wanted to know which famous person was getting a historical marker. That shows what we have come to expect of markers, and how much work there is to be done for popular conceptions of history. This is the first historical marker that acknowledges that black miners played a role in Illinois history. It uses the story of Stephens, whose words we know through the poet and journalist Carl Sandburg from his poem “The Sayings of Henry Stephens.” Sandburg always claimed the poem was “a transcript” of Stephens’s words, and asks us to imagine what solidarity could mean.

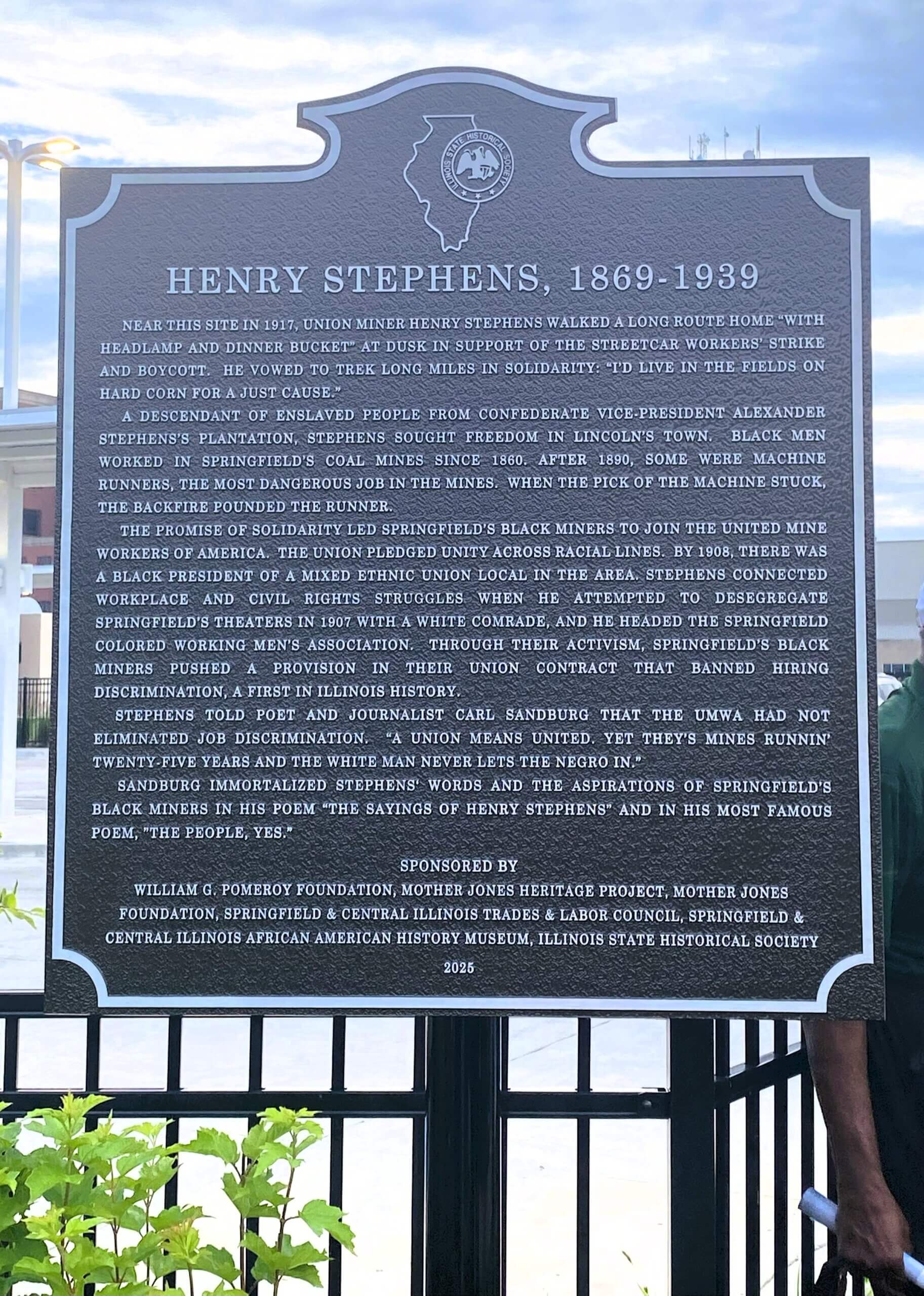

The marker text reads:

“Near this site in 1917, union miner Henry Stephens walked a long route home ‘with headlamp and dinner bucket’ at dusk in support of the streetcar workers’ strike and boycott. He vowed to trek long miles in solidarity. ‘I’d live in the fields on hard corn for a just cause.’

A descendant of enslaved people from Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens’s plantation, Stephens sought freedom in Lincoln’s town. Black men worked in Springfield’s coal mines since the 1860s. In the 1890s, some were machine runners, the most dangerous job in the mines. When the pick of the machine stuck, the backfire pounded the runner.

The promise of solidarity led Springfield’s black miners to join the United Mine Workers of America. The Union pledged unity across the racial lines. By 1908, there was a black president of a mixed ethnic union local in the area.

Stephens connected workplace and civil rights struggles when he attempted to desegregate Springfield’s theaters in 1907 with a white comrade, and he headed the Springfield Colored Working Men’s Association. Through their activism, Springfield’s black miners pushed a provision in their union contract that banned hiring discrimination, a first in Illinois history.

Stephens told poet and journalist Carl Sandburg that the UMWA had not eliminated job discrimination. ‘A Union means united. But they’s mines runnin’ twenty-five years and the white man never lets the negro in.’

Sandburg immortalized Stephens’ words and the aspirations of Springfield’s black miners in his poem ‘The Sayings of Henry Stephens’ and his most famous poem, ‘The People, Yes.’’

Sponsored by the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, the Mother Jones Heritage Project, the Mother Jones Foundation, Springfield and Central Illinois Trades and Labor Council, Springfield and Central Illinois African American Museum, and the Illinois State Historical Society.

The marker came about after the 2020 George Floyd uprisings, when the Illinois State Historical Society and the Pomeroy Foundation made a call for more historical markers that highlighted diverse stories. These large markers are costly. The Mother Jones Heritage Project, of which I am director, has erected other markers, and has built a robust network. Even before I had drafted the marker text, a coalition came together. The Springfield-based Mother Jones Foundation raised a significant portion of the cost at their annual dinner. Local activist Terry Reed spearheaded a major donation from the Springfield and Central Illinois Trades and Labor Council. Reed connected us to Aaron Guernsey of the Building Trades Council of Springfield, who succeeded in getting the marker placed at the new Springfield Transportation Hub. When completed, the Hub will have significant foot traffic as a major midwestern transit stop. That location is close to where Stephens lived, so we feel positive that it was near this location that Stephens walked in solidarity. We also gained support from the Springfield and Central Illinois African American Museum.

As with all markers, many sign-offs were needed, including from the Transit Authority. We waited to dedicate the marker in anticipation of completion of the Hub, but that still faces continued Congressional haggling and the Trump rollbacks. Finally, we decided to dedicate the marker before the hub was completed.

For the marker text, I am grateful for feedback from Terry Reed, Joseph Rathke, Dave Rathke, Kamau Kemayo, Bill Furry, and members of the Illinois State Historical Society Markers Committee and the Mother Jones Foundation. Terry Reed was also important in originally alerting me to the poem, many years ago and in helping with some of the initial research.