Alan Singer’s new book excavates the Central Pennsylvania miners as they struggled at multiple levels: against mechanization, for democracy in their union, the United Mine Workers of America. Singer tracks them as fought open shop drives, attempted to bring a program for nationalization of the mines, took on the increasingly autocratic John L. Lewis in the context of the roll-back of the union movement.

What originally brought you to this project, and what motivated you to bring the project out in book form now?

I am a 1960s era anti-war and civil rights activist and community organizer interested in the dynamic of movements for social change, particularly the Gramscian concept of organic intellectuals for the working class and marginalized groups. Over the years I have been a member of the New York City taxicab drivers’ union, a teamster, a member of the transit workers union, a member of the UFT local of the AFT, and more recently a member of the AAUP/NYSUT.

I began the project that became Class-Conscious Coal Miners: The Emergence of a Working-Class Movement in Central Pennsylvania, in the 1970s as doctoral research when I traveled to Central Pennsylvania coalfields to interview retired miners about their experiences in 1920s strikes and labor organization. Between World War I and the end of World War II, Pennsylvania bituminous coal miners near Johnstown and Pittsburgh were amongst the most militant unionized workers in the United States. My original plan was to study garment workers in New York City, but many of the documents in the ILGWU archives were in either Yiddish or Italian. It was easier to drive to Central Pennsylvania and research coal miners than to learn two new languages. My dissertation and the book draw on interviews with former miners, census records, library, union and government archives, cultural artifacts, union and leftwing publications, newspaper and magazine coverage of events, and coal miner songs. For most of my career I have been a secondary school teacher and a university-based teacher educator. My research in education has focused on transforming teacher and student understanding about the world they live in and students as potential organic intellectuals for social change movements. My interest in transformative consciousness brought me back to my earlier work on the miners.

Many historians tend to think that the history of miners has been well-trod. Can you tell readers a few things that they might find that help us understand that the full story of miners has not been fully told?

The history of the United Mine Workers of America and the role of UMWA President John L. Lewis in the labor movement has been examined extensively. My work is on rank-and-file miners and the development of working-class consciousness. In the 1920s Central Pennsylvania coal miners defied the national leadership of the UMWA and mounted campaigns to organize non-union miners in neighboring fields. During the Great Depression coal miners played a major role in organizing workers in other industries and during World War II they defied President Roosevelt and the federal government and went on strike against wage freezes and corporate profiteering. One of my major findings is that class consciousness should be seen as fluid, rising and falling depending on conditions in people’s lives.

How did mining communities shape what you say in your title: class consciousness?

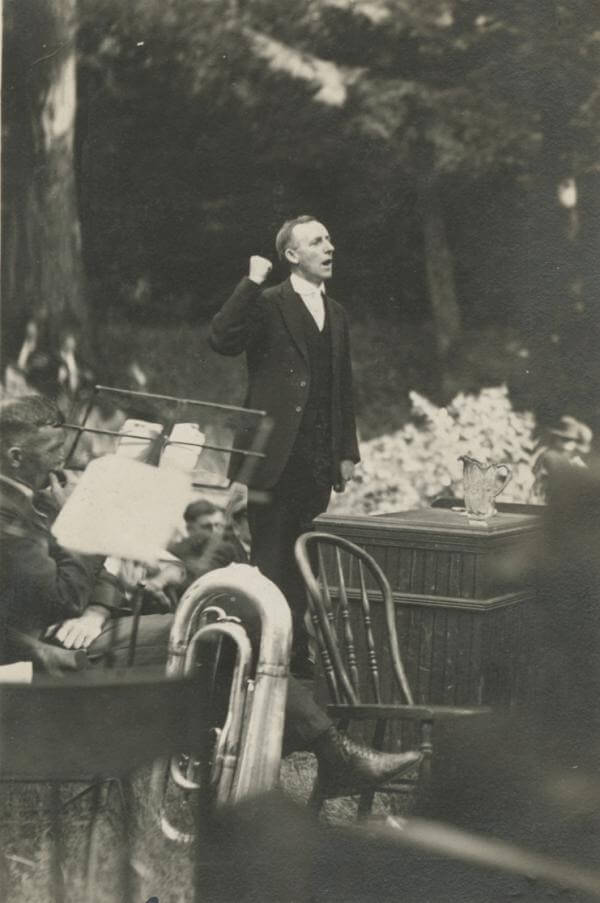

A number of factors contributed to the development of class consciousness in bituminous coal mining communities. Hand-picked bituminous coal miners worked in isolation deep underground and were virtually impossible to supervise. They decided when coal seams were safe, chose how much to work, and resisted corporate efforts to reorganize production along factory lines, undermining what they considered the Miner’s Freedom. Constant danger contributed to group solidarity. New miners, often sons, other relatives, and immigrants from a miner’s European village, learned their craft and commitment to union from older miners. In addition, most mine patches were isolated in mountain areas. Miners had little choice but to purchase necessities from the company store and rent homes from the coal companies which was a constant source of tension. When work was slack, when a miner was injured, or when a family member was sick, miner families fell into debt to the company store. One of District 2’s innovations to support striking miners was the Labor Chautauqua modeled on religious tent revival meetings. They offered entertainment and education classes and helped build community spirit. Women were not legally permitted to work in the coalfields of the United States prior to the 1940s, although some women always worked in small family leased bank mines, mines carved directly into the hillside. Although they were not miners, women, mothers, wives, and daughters were key to the success of worker struggles. In 1924, Heisley, one of the largest coal companies in Cambria County with 564 employees, announced it was closing its operation and would reopen non-union. Women were at the forefront of organized opposition to the company’s actions and eleven women were arrested for “appearing at the homes of Heisley employees and making insulting remarks, as well as hooting at the workmen going to and from work.”

Why was there so much dissent against the leadership of the United Mine Workers of America, a union that is often valorized, while the level of dissidence long forgotten. Why is it important to remember that dissidence?

There were a number of factions within the UMWA. The union had a federal structure with national and state offices and sub-districts within states and different coal fields. The national office had a business-unionist philosophy and tried to consolidate control over the union by cooperating with management groups and during wartime with the federal government. It promoted a uniform contract in what was considered the Central Competitive Field (CCF) consisting of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Western Pennsylvania and was willing to sacrifice the interests of miners in outlying and non-union fields. In well-organized districts like Illinois and in districts outside the CCF like Kansas, opposition leaders demanded more local control over contract negotiations. District 2 in Central Pennsylvania was outside the CCF because narrow coal seams meant workers had to push coal cars closer to the main shafts which increased the cost of production. The nature of work, treatment by the national and District union officials, corporations, and federal and state governments led to continuous rank-and-file unrest including wildcat strikes and the emergence of organized opposition groups in District 12 (Illinois), District 2 (Central Pennsylvania) and in District 5 (Western Pennsylvania) where leaders of the opposition miners had ties to the Communist Party. It was amongst these rank-and-file opposition groups that we see the emergence of class-consciousness.

You use a bottom-up perspective to understand the role of union dissident (and later CIO leader) John Brophy. How does the wider world of Pennsylvania miners give a better sense of Brophy’s life?

Most of the interviews I did with retired coal miners focused on events in Central Pennsylvania’s District 2 and the town of Nanty-glo Pennsylvania between World War I and 2. I selected District 2 and Nanty-glo because important leadership of the militant opposition forces in the UMWA came out of District 2 and Nanty-glo. I did extensive interviews with Brophy’s niece and her husband about conditions in the town of Nanty-glo and its mines that shaped the District 2 challenge to the business unionism of John L. Lewis and the UMWA national office. John Brophy, President of the District from 1916 until 1927, had been active in organizing the Nanty-glo locals and his brother-in-law and friends remained active there when he moved to the District office. Brophy headed the UMWA committee exploring nationalization of the mines after World War I, developed innovative labor education campaigns and organizing strategies to combat open shop drives by coal operators during the 1920s in conjunction with labor movement progressives, unsuccessfully ran against John L. Lewis for union president in 1926 in an election tinged by massive fraud, was banned from the UMWA because of his opposition to Lewis, and in the 1930s was instrumental in the organization of the CIO. Because of Brophy’s activities and journals and letters written by Powers Hapgood, a Brophy protégé who became a labor and socialist organizer after graduating from Harvard University, efforts to build on the class-consciousness of District 2 miners as they fought against the 1920s open shop campaign were well documented.

This has the texture of a place-based narrative. Tell us what you discovered about these long-forgotten places such as Nanty-Glo, Pennsylvania.

The dissertation took the struggle of the rank-and-file movements in communities like Nanty-glo up until the start of the Great Depression when the industry and the opposition groups collapsed. Communist miners, barred from the UMWA, tried to continue organizing as part of a new union, but met with little success. The book, however, looks at the revitalization of the national UMWA and locals in towns like Nanty-glo during the thirties and forties. After World War II, the shift to oil and new mining techniques decimated the UMWA and coal mining communities. One of the things I found was that with the loss of union and work as a source of identity, consciousness shifted. In the 2016 and 2020 Presidential elections, communities that previously supported a militant working-class movement were major sources of support for Donald Trump’s Presidential campaigns.

Alan Singer is a social studies educator and historian in the Department of Teaching, Learning and Technology at Hofstra University, Long Island, New York. He is a former New York City high school teacher and regularly blogs on Daily Kos and other sites on educational, labor, and political issues. Dr. Singer is a graduate of the City College of New York and has a Ph.D. in American history from Rutgers University. He is the author of Education Flashpoints (Routledge, 2014), Teaching to Learn, Learning to Teach: A Handbook for Secondary School Teachers, 2nd edition (Routledge, 2013), Social Studies For Secondary Schools, 5th Edition (Routledge, 2024), Teaching Global History, 2nd Edition (Routledge, 2020), Teaching Climate History (Routledge 2022), New York and Slavery, Time to Teach the Truth (SUNY, 2008), New York’s Grand Emancipation Jubilee (SUNY, 2018), and Class-Conscious Coal Miners (SUNY, 2024). He is the co-author of Supporting Civics Education with Student Activism (Routledge, 2021). He was a participating historian in “Defining Moments: The Civil Rights Movement in North Hempstead,” co-director of the New York State Great Irish Famine Curriculum Guide, and the editor of the “New York and Slavery: Complicity and Resistance” curriculum guide. Both curriculum projects were recipients of National Council for the Social Studies Program of Excellence Awards. He is a DEI curriculum consultant with the Bridging Cultures Group.