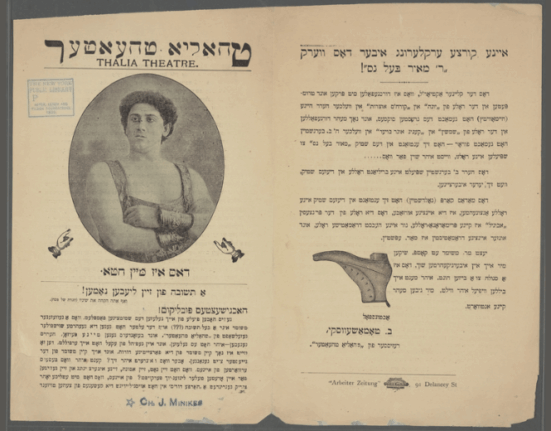

In fall 1936, the Chicago Public Library initiated the Chicago Foreign-Language Press Survey, with funding from the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA), one of the New Deal programs designed to provide unemployment relief and support engagement in cultural production. Over the next five years, the survey workers collected, transcribed, translated, categorized, and catalogued close to fifty thousand articles from twenty-two ethnic newspapers circulating in the city of Chicago from the 1860s to the 1930s—some 120,000 pages typed! These included articles from mainly Czech, Danish, German, Greek, Jewish, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Russian, and Swedish newspapers, with a small collection of Albanian, Chinese, Filipino, Serbian, and Slovene publications. Major collections range from the Abendpost to the Denní Hlasatel to the Dziennik Chicagoski to the Jewish Daily Forward to the Naród to the Rassviet to the Svornost to the Saloniki. The originals can be found at the Special Collections Research Center of the University of Chicago. However, starting in 2009, the Newberry Library took the Foreign-Language Press Survey online with a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.[1]

Although there is a wide and deep historiography at the intersection of labor history and immigrant and ethnic history, Leon Fink’s The Long Gilded Age: American Capitalism and the Lessons of a New World Order has confronted earlier issues of underplaying transnational currents in U.S. labor history (for fear of charges of un-Americanism, red-baiting, etc.) and called upon scholars to unapologetically do so.[2]

Working with the Chicago Foreign-Language Press Survey offers students the chance to engage in this project. Chicago was a center, if not the center, of labor organizing and immigrant/ethnic life in the seven-decades-long era spanned by the CFLPS, which witnessed the Great Railroad Strike, the Haymarket Affair, the Pullman Strike, the 1893 World’s Fair, Red Summer, and the rise of the CIO and New Deal. At the time of the Haymarket Affair, forty percent of Chicago’s population were immigrants (primarily German, Polish, Scandinavian, and Irish), who comprised sixty percent of the city’s workforce. This archive presents a way to access certain voices of workers who may not have been represented by or organized within the American Federation of Labor, which was sometimes nativist. Moreover, Chicago’s German-language press, for instance, enables students to critically interpret class and generational dynamics from within immigrant and ethnic communities.

The Assignment: Keywords in Translation

When I’ve taught Labor and Working Class History at UMass-Boston (2018) and Work, Culture, Power in U.S. History at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, MA (2020, 2023, 2024), I’ve asked students to look out for an interesting keyword in the assigned readings and then find a cluster of articles mentioning the term in the Chicago Foreign-Language Press Survey. They then write a five-page interpretative essay based on the combination of the cluster of primary sources and the secondary literature that inspired their search.

Assignment Description: Primary Source Analysis

During the weeks devoted to Reconstruction, the Gilded Age, and Progressive Era, be on the lookout for interesting terms, events, labor organizations, corporations, laws, technologies, etc. mentioned in the assigned readings. Then search for this keyword within the database of historical immigrant and ethnic newspapers, the Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey (https://flps.newberry.org/).

Once you have found two or three articles in the Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey mentioning your search term, write a five-page interpretative essay (12-pt font, double- spaced).

Analysis of primary sources from the Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey

You should summarize the articles and analyze their main claims about the keyword you’ve searched. What are the political viewpoints expressed in the articles? What might the intended audience have been? Who did the newspaper (claim to) represent in terms of ethnicity, partisanship, class, etc.? Do the articles differ from one another in any interesting ways? If so, what might explain the divergence? Which significant events in the immediate surrounding period could have contributed to the context of writing and publication? Is there discernible change over time?

Contextualization with course materials

Your essay should contextualize the primary sources from the Foreign Language Press Survey by using our assigned primary and secondary readings and/or lecture materials. How do the previously assigned materials aid in analyzing the references or arguments within the primary sources? How do your primary sources shed new light on the event, organization, or phenomenon that appeared in the readings or lecture? What further questions might they provoke when read in tandem with existing interpretations by the historians we’ve read (or myself in lecture)?

Some Examples of Student Learning

Inspired by Moon-Ho Jung’s Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation, students have analyzed usages of the term “coolie” in various European immigrant newspapers of the Gilded Age.[3] Inspired by Amy Dru Stanley’s Journal of American History article “Beggars Can’t Be Choosers: Compulsion and Contract in Postbellum America,” Biology major Isabelle Uong (Holy Cross ’22), delved into divergent views within immigrant communities on begging, criminalization, charity, and mutual aid, analyzing where they affirmed and departed from the ideas associated with the punitive austerity and Gilded Age liberalism of such figures as William Graham Sumner.[4] Inspired by Joseph McCartin’s Labor’s Great War: The Struggle for Industrial Democracy and the Origins of Modern American Labor Relations, 1912-1921, Connor Murphy (Holy Cross ‘21) decided to explore how immigrant and ethnic newspapers conceived of and contested the meaning of “industrial democracy.”[5] Inspired by Thomas Andrews’s Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War and lecture material on the 1902 Anthracite Strike, one student at UMass-Boston in 2018 found an amazing effort by Polish-American newspapers to reveal the real political economy of coal-mining.[6] The student found these articles comparing the wages of co-ethnics in the Pennsylvania coal fields to the prices charged to consumers in Chicago.

Several years later, another student, pre-med Carter Titus (Holy Cross ’25), also drew inspiration from Andrews’s book and the Colorado PBS Documentary on the Ludlow strike and massacre. (See Titus’ essay excerpt at end of essay, in blue print)

Occasionally, a student has begun by searching in the CFLPS with a general term such as “strike.” This led History major John Larsen (Holy Cross ‘23) to explore the affective dimensions of whether to strike among Scandinavian Chicagoans during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Larsen wrote about what he called the “socio-economic politics of fear.” (See Larson’s paper excerpt at end of essay, black print).

The assignment is also an opportunity to discuss with students the making of an archive—and the role of New Deal programs in doing so. In her classic Making A New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939, Lizabeth Cohen countered the notion that the 1920s constituted an altogether fallow period for labor organizing.[7] Rather, she traced how workers in Chicago shifted away from relying on immigrant and ethnic communities for sustenance in times of need and social lives in times of plenty. Instead, they found themselves engaged in mass media and consumption, and turning to the institutions and activities—mortgage programs, company baseball teams—of welfare capitalism (soon to be revoked by corporations in the Great Depression). Transformations in habits, expectations, and communities would enable the galvanizing of a working class in Chicago in the era of the major CIO campaigns. This was also, Cohen argues, the moment when the New Deal made the state markedly more visible to working-class Chicagoans…through such projects at the WPA-funded Chicago Foreign-Language Press Survey.

In the Chicago Foreign-Language Press Survey itself, one can discern a labor history of its own. The Survey relied on translators, editors, typists, and proofreaders, with the support and oversight of project editors and scholar-directors at Northwestern University and the University of Chicago, especially historian Bessie Louise Pierce. In addition to the WPA and the Chicago Public Library, the Newberry Library, the John Crerar Library (University of Chicago), and the Chicago Historical Society provided resources.[8]

The work process of assembling the archive reflected the methods and concepts of the era’s social sciences alongside the political culture of the New Deal initiative.[9] The project editors designated categories for the material, by ethnic group and by subject codes such as “Attitudes,” “Social Organization,” “Contributions and Activities,” and “Assimilation.”[10] They saw their goal as investigating how immigrant and ethnic communities had made a composite city of “American” and foreign cultures in Chicago. The project directors and editors hired the translators and assigned them historical newspapers. Significantly, in going through the newspapers, the translators were tasked with finding articles that would fit within one or more of the predefined subject codes. Following initial translation, editors reviewed the work, asked for changes, and sometimes rejected articles. While the CFLPS is a rich resource, one wonders what sources and related histories sit in its scrap-pile. Finally, proofreaders revised each article’s text for English prose.[11] (Now that more historical newspapers have been digitized, one could envision a project in a language class to find the original article translated in the CFLPS and compare the language and content!)

My CFLPS assignment largely bypasses the categorization of the original archive, depending instead on keyword-search by students. Nevertheless, a project in its own right could involve researching and critically analyzing the making of the archive and its categories. How did the disciplines of History and Sociology at the University of Chicago influence the project’s mission and the ultimate structure of the archive? (Sociologist Robert Park, who viewed human society as an ecological organism with patterns, comes to mind.) How did academic researchers connect with translators and typists hired under WPA auspices? If it hasn’t been done already, this undertaking might be better-suited to Chicago-based colleges and universities with access to physical archives there. For now, we in Worcester, MA will make the most of the digitized CFLPS archive.

Although the Chicago Foreign-Language Press Survey enables students to access newspapers published in multiple languages in English, I hope it will inspire some of them to take up or continue language study, as they become aware that resources such as this one, as amazing as they are, barely scratch the surface. I was first introduced to the CFLPS by Prof. Kathleen Neils Conzen, when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Chicago. I went on to take two years of German there, and write a BA thesis on the political engagement of German revolutionaries of 1848 in the U.S. before, during, and after the Civil War. Eventually, during dissertation research, I’d land in state and firm archives related to work, knowledge, and power in engineering industries from Cologne to Chemnitz (Köln to Karl-Marx-Stadt?).

As search engines degrade into AI-generated nonsense, I hope that working with the Chicago Foreign-Language Press Survey archive will not only pique students’ curiosity, but also underscore the power of meaning and context. For some, the project also ends up entailing a delve into their family or regional roots; for others, rethinking assumptions about immigration; for yet others, both. I hope it will allow them to recover the struggles and strategies of working people from the “long Gilded Age” to making a New Deal.

Header Image: Zgoda print shop and Polish National Alliance building at 1414 (then 112) W. Division St., Chicago. 1889. Image provided by The Polish Museum of America. Published at Illinois Newspaper Project.

Two Keyword Assignment Samples

[1] “About the Press Survey,” Newberry Library (2021): https://flps.newberry.org/#/

[2] Leon Fink, The Long Gilded Age: American Capitalism and the Lessons of a New World Order (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014).

[3 Moon-Ho Jung, Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006).

[4] Amy Dru Stanley, “Beggars Can’t Be Choosers: Compulsion and Contract in Postbellum America,” The Journal of American History 78, no. 4 (1992): 1265-1293.

[5] Joseph McCartin, Labor’s Great War: The Struggle for Industrial Democracy and the Origins of Modern American Labor Relations, 1912-1921 (UNC Press, 2017 [1997]).

[6] Thomas Andrews, Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War (Harvard University Press, 2008).

[7] Lizabeth Cohen, Making A New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939 (Cambridge University Press, 2014 [1990]).

[8] Guide to the Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey Records, 1861-1938 (2007): https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/scrc/findingaids/view.php?eadid=ICU.SPCL.CFLPS

[9] Joshua M. Lupkin, “Guide to the Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey,” University of Illinois, (2008): https://guides.library.illinois.edu/cflps

[10] Guide to the Chicago Foreign Language Press Survey Records, 1861-1938 (2007): https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/scrc/findingaids/view.php?eadid=ICU.SPCL.CFLPS

[11] “About the WPA Project,” Newberry Library (2021): https://flps.newberry.org/#/

Author

-

LIat Spiro is Assistant Professor and Alexander F. Carson Faculty Fellow in the History of the United States at College of the Holly Cross. Her dissertation, "Drawing Capital: Depiction, Machine Tools, and the Political Economy of Industrial Knowledge, 1824-1914," was completed at Harvard University.