Charisse Burden-Stelly recently published Black Scare / Red Scare: Theorizing Capitalist Racism in the United States. The book offers a radical and interdisciplinary analysis of the ways anti-Black racial oppression infused the U.S. government’s anti-communist repressions over the long mid-20th Century beginning in 1917. It argues that anti-radical repression is inseparable from anti-Black oppression, “and vice-versa.” Ian Rocksborough-Smith interviewed her for Labor Online about this important and vital work.

Rocksborough-Smith: What led you to write a book about this subject?

Burden-Stelly: The book takes up the thread of inquiry in my dissertation, “The Modern Capitalist State and the Black Challenge: Culturalism and the Elision of Political Economy,” that examined a phenomenon I called anticommunism/antiradicalism/antiblackness in US society. That clunky concept was simplified to Black Scare/Red Scare for the text. Ultimately, I was interested in how the struggle for Black liberation (and African decolonization) became linked to “foreign influence” and “communist” machinations; and how one threat of anticapitalist ideas and struggle was social equality for Black people. Figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and Claudia Jones and organizations like the National Committee to Defend Negro Leadership and the National Negro Congress were foundational to understanding that connection. I was also interested in theorizing what the kind of society was, i.e., US Capitalist Racist Society, that would set to work instrumentalities like the Black Scare and the Red Scare to maintain an exploitative political economy rooted in racial hierarchy.

The Black Scare and the Red Scare both seem like parallel but intimately related phenomena over the course of the long-mid 20th Century. Could you explain how you might see them as related but distinct phenomena? It seems like one needs to consider them both together or else risk reproducing historical erasures.

The Black Scare is the historically and contextually situated debasement, distortion, criminalization, and subjection of Blackness rooted in dread and fearmongering about Black social equality, political domination, and economic parity, on the one hand, and the displacement, devalorization, and devaluation of whiteness, on the other hand. The Red Scare is the criminalization and condemnation of anticapitalist ideas, politics, and/or practices through discourses of radical takeover, infiltration, and disruption of capitalist racism in the United States. The Red Scare has been most prominently articulated through the threat of the communist/Bolshevist and the fellow traveler, though it also applied to other types of radicals like anarchists, Wobblies, and labor militants.

I refer to the connection between them as “interaction metaphors,” a concept I borrow from Nancy Leys Stepan. Black informs Red as constitutively antithesis, alterity, and threat to capitalist accumulation, property relations, and social hierarchy at the same time that Red reifies Black as subversion that must be suppressed and eradicated. Likewise, the Black “renders visible” the non-citizenship and unbelonging of the Red, and vice-versa. With interaction metaphors, “meaning is a product of the interaction between the… two parts of the metaphor.” Such interaction renders legible the threat of the Black and the Red and substantiates the use of the Black Scare and the Red Scare as instrumentalities instantiated in US Capitalist Racist Society. These include the curtailment of movement, the denial of civil rights and liberties, prosecution without due process, and physical and financial terrorism. The historical abjection of the Black as embodied menace to the racialized socioeconomic order, and the repression of the Red that likewise threatened the expansion of capital organized through Wall Street imperialism, are “active together” to fix the boundaries of Americanness, whiteness, citizenship, and belonging. Here, the Black Scare and the Red operate as mutually reinforcing technologies of discipline and punishment necessary to ensure national security through the expulsion, exclusion, and containment of those deemed inexorably illegitimate.

Black Scare/Red Scare importantly elevates and amplifies voices from the Black Radical tradition of the mid-20th Century. From the prolific writings of Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois in his elder years to groups like the Civil Rights Congress and the National Negro Labor Congress which were active through the early 1950s but faced severe repressions from the state. Moreover, it foregrounds the ideas and writings of under-appreciated radical Black women in the historical record—folks like Freedomways founding editor, Esther Cooper Jackson—who feature prominently in your citations. As such, how would you characterize your main source materials for this book and how might you describe your method for assembling these sources?

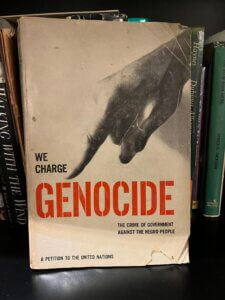

I used state documents like Revolutionary Radicalism (commonly known as the “Lusk Committee Report”) and J. Edgar Hoover’s Racial Conditions in the United States (RACON); the We Charge Genocide petition; and a range of archival documents, including meeting minutes and reports, radical newspapers and periodicals, correspondence, and speeches. Gerald Horne’s endnotes in books like Black Liberation/Red Scare: Ben Davis and the Communist Party, Communist Front? The Civil Rights Congress, 1946-1956, and Black Revolutionary: William Patterson and the Globalization of the African American Freedom Struggle helped to guide me to key archives and sources and provided a starting point for identifying the types of racist and antiradical repression to which Black communists and fellow travelers were subjected. From there, the writings and speeches of people like William Patterson, Claudia Jones, Ben Davis, Pettis Perry, W. Alphaeus Hunton, and Charlotta Bass, along with Angelo Herndon’s autobiography Let Me Live, provided the backbone of my historical narrative and the spotlight for key events.

The Black Scare and Red Scare periods were marked by intense public fears and suspicions of certain groups within American society. Together, they reveal the longue durée, as you put it so eloquently in the book, of various forms of especially racial subjugations, but also “Wall Street Imperialism” and its long deleterious reach in American life (historical and present-day). How does the book analyze the role of propaganda and media in perpetuating these fears among American publics which have (willingly or not) propped up systems of white supremacy and obscured many of the realities of Black American life especially through the mid-20th Century? And what impacts have these mechanisms had on public perceptions of these matters moving forward in time?

One way I write about this is through the concept of “societal self-regulation. Propaganda left a large swath of the population in fear that their thoughts, beliefs, and opinions would result in disciplining given an atmosphere that had been “poisoned” by the passage of such laws. The radical Pan-Africanist Eslanda Goode Robeson explained how not only the threat anticommunist laws, but also the spread of Black Scare/Red Scare misinformation and disinformation undermined progressive struggles, not least the struggle for racial justice, since citizens were plagued by “fear of losing one’s job, home, education” and “fear of non-conforming, or of even being accused of non-conforming.” This “soft power” of anticommunist governance meant that racially and politically minoritized persons were forced to genuflect to the status quo lest they be marginalized, excluded, criminalized, physically attacked, or worse. Likewise, those with access to power—including landlords, private employers, book publishers, and mass media workers—were conditioned by and through the Black Scare and the Red Scare to be hostile to and prejudiced against communists, militants, and agitators and to act against them. As an article in the progressive Black publication, the California Eagle, claimed, the persecution of communists and their right to free speech had especially dire consequences for Black people, for whom the right to dissent was essential to challenging racism and white supremacy.

Paid informants, infiltrators, stool pigeons, and turncoats also represented the use of anticommunism by other means. These ordinary citizens cooperated with the government and were compensated to insinuate themselves into the organizations and lives of those suspected or accused of radicalism, in order to procure—or to manufacture—information. They were given the tools and incentives of infiltration, and in turn, they gave information that confirmed suspected subversion and created new targets.

The use of mass media and infiltrators have been exacerbated today by the use of social media to discredit radical movements. We see this, for example, with the Stop Cop City movement in Atlanta and pro-Palestine protests throughout the nation. The hostile position of the government, whether at the state or federal level, is parroted, disseminated, and intensified by the mainstream media, which takes advantage of the abysmally low media literacy (and functional illiteracy) of the majority of the US populace.

The Black Scare clearly disproportionately targeted African Americans as part of a longer history of hyper-exploitation connected to global systems of ongoing racial capitalism and imperialist accumulations – a history that clearly extends beyond the temporal scope of your book (ie. from before the 1600s to the 21st Century etc…). Given this context, how does Black Scare / Red Scare ultimately see the conjunctures of mid-20th Century McCarthyist fascism and repressions? Why is this moment so critical to understand for the long durée histories the book clearly gestures to as well?

I’ll answer this question by highlighting the passage and application of a litany of legislation, including the “thought control” Smith Act, the McCarran Act, the McCarran-Walter Act, and the Communist Control Act. These conveyed to many of its victims that McCarthyism and fascism were two sides of the same coin. This moment of the Red Scare is particularly important because it represented the consolidation of earlier moments of antiblack and antiradical repression that saw, for instance, the passage of the Espionage Act and Subversion Acts during World War I and the passage of the McCormack Act in the late 1930s during an upswing in anticommunist hysteria. People like Claudia Jones believed that the roundup of communists under the Smith Act was a Red Scare attempt to crush those who understood the intersections of racism, capitalism, and war. After she was convicted in 1953, she queried in her speech to the court, “Is all this [the trial and conviction] no further proof that what we were also tried for was our opposition to racist ideas, an integral part of the desperate drive by men of Wall Street to war and fascism?” In an address to the court two years earlier, Jones’s co-defendant Pettis Perry argued that depriving communists of their right to write, speak, assemble, and publish, along with outlawing ideas, which was the primary goal of the Smith Act, were big steps on the path to fascism. He lamented, “The very fact that this trial, a trial of ideas and books, can take place in our country shows how far the Wall Street rulers have taken our country down the disastrous path of fascism.”

US involvement in the Korean War was key to the creeping fascism of the McCarthyist era. The drafters of “We Charge Genocide” argued, for example, that the increased terror against African Americans could be accounted for by the Cold War and the drive to another world war, and that this, in turn, was the basis for aggression in Korea. “The jelly bombs dropped in Korea,” the Petition argued, “proves that racism is an export commodity to be forced upon colored peoples.” The fate of the superexploited in the United States was thus the fate of mankind because “the continuance of this American crime against the Negro people of the United States [would] strengthen those reactionary American forces driving towards World War III…” Further, “White supremacy at home [made] for colored massacres aboard” since both were predicated on fascistic disdain for racialized life. As well, “The lyncher and the atom bomber [were] related. The first cannot murder unpunished and unrebuked without so encouraging the latter,” with the intimate link between the two being “economic profit and political control.”

Looking at the legacies of the Black Scare / Red Scare, what lessons can we draw from these episodes in American history for today? How do you see the echoes of these movements in contemporary society, and what measures can we take to prevent similar instances of mass hysteria and persecution in the future (if this has not already happened with the ways things like DEI and CRT are now targeted)?

Part of what my analysis conveys is that there is no way to prevent mass Black Scare/Red Scare hysteria because it is foundational to and endemic in US Capitalist Racist Society. Such hysteria is crucial to beating back movements for racial justice, economic redistribution, and durable peace. This is evident in accusations of foreign influence on the 2020 George Floyd uprisings; Chinese backing of protests against the US-NATO-backed war in Ukraine; and “outside agitation” propelling Stop Cop City activism. It is also evident in the outsized repression of Black and brown pro-Palestine protestors in the current moment. The targeting of the latter activism on college campuses has been entangled with a fierce attack on “DEI,” whose primary targets have been Black administrators, irrespective of their political orientation. Though we cannot stop these durable attacks, we can combat them through joining movement organizations, engaging in collective political education, and embracing internationalism in our analysis and activism to create links between, for example the militarization of racialized communities, the imminent invasion and ongoing UN/Core Group occupation of Haiti, the war-intensified genocide in Gaza, and the decades-long neocolonial war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The right-wing and the ruling class are organized and internationalist, which make their propaganda and repression so effective. We cannot continue to let those factions set the agenda. Everything is at stake.

What are you working on next?

I am currently working on a book project tentatively titled, “Mutual Comradeship: Radical Blackness, Love, and Solidarity.” I define mutual comradeship as radical African descendants’ ethical, political, and epistemological practices at the intersection of struggle on behalf of the racialized, colonized, and oppressed and protracted antiradical state repression. Its foundation is collaboration, reciprocal care, and learning in community rooted in organizing, movement building, collective self-defence, and guerilla scholarship. The book is situated in the era spanning 1947-1957, and each chapter is organized around a different practice of mutual comradeship, including organizing for Rosa Lee Ingram, the drafting and circulation of “We Charge Genocide”, and the formation of the National Negro Labor Council.

Additionally, I am currently on fellowship at the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History, and the theme of this year’s workshop is “The Future of Black Power Studies: Ideas, Institutions, Insurgencies.” I am working on a journal article titled, “Antecedents of Black Power in the McCarthyist Conjuncture” in which I am analyzing resonances in analyses of triple oppression, imperialism, fascism, and war.

Ian teaches primarily U.S. history at the University of the Fraser Valley in Stó:lō / S’ólh Téméxw / Abbotsford, B.C., Canada. His research interests include public and urban history, social movements, and histories of race, labor, religion, and empire in the Atlantic world. He has published academic articles and book reviews in a variety of journals like The Black Scholar: Journal of Black Studies and Research, Reviews in American History, and The Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society and has a book entitled: Black Public History in Chicago: Civil Rights Activism from World War II Into the Cold War (April/May 2018). He has written op-eds in Canadian Dimension and The Conversation (Canada) and is on the editorial team for Labor Online (LAWCHA). He has served as an international solidarity and human rights officer for his faculty union, local 7 of the Federation of Post-Secondary Employees of British Columbia (2021-2023).