This is part of a series featuring authors of essays in the journal Labor: Studies in Working Class History. Eric Arnesen discusses the main arguments of his recently published essay on the National Negro Congress and shares some great images and documents from his research. The full essay appeared in the 20:1 (March 2023) issue of the journal. Subscriptions are part of LAWCHA membership.

Two decades before Rosa Parks and the Black community of Montgomery, Alabama launched what is known as “the modern civil rights movement” in 1955, activists met at Howard University in Washington, D.C. to discuss “The Position of the Negro in our National Economic Crisis.” Most of those attending found the Roosevelt Administration’s New Deal to be inadequate to the task of addressing the Great Depression and injurious of Black workers’ interests. In the months that followed, they laid the groundwork for a new organization, the National Negro Congress (NNC), that promised to serve as a “weapon for Negro rights” by uniting a broad range of organizations, promoting grassroots protest, and advocating on behalf of interracial labor unity.

Its founding convention in Chicago in February 1936 won accolades from many Black journalists and editors. “No more significant event has been recorded in the post-Emancipation history of the Negro in America,” the Indianapolis Recorder concluded with some degree of hyperbole. The 1936 gathering evinced “such enthusiasm, such sustained interest,” the National Urban League’s Lester Granger explained, that was “indicative of a deep rooted and nationwide dissatisfaction of Negroes that rapidly mounts into a flaming resentment.” Departing delegates “took with them this new hope” and had “laid the basis for building unity, for augmenting their power and their strength,” the young Communist writer Richard Wright concluded. The new association represented the “popular front” in action, uniting liberals, Communists, and some socialists in a coalition that appeared ready to tackle aggressively the myriad crises afflicting Black America.

How this Popular Front coalition came into existence is one of the themes explored in my article, “The Making and Breaking of a Popular Front: The Case of the National Negro Congress,” which appears in the 20:1 (March 2023) issue of the journal Labor: Studies in Working Class History. One part of the story is a familiar one to historians. Deeply worried about the rise of fascism, the Communist Party rethought its sectarianism and sought to build bridges to non-Communist progressives to better meet the challenges of depression-era America. They edged closer to this position even before the Comintern declared the Popular Front to be the new policy in August 1936. But non-Communists, for their part, also had to conclude that there were advantages to working with the Communists with whom they sharply disagreed on organizational and ideological matters and had bitterly fought with – sometimes literally – over the course of the depression’s early years.

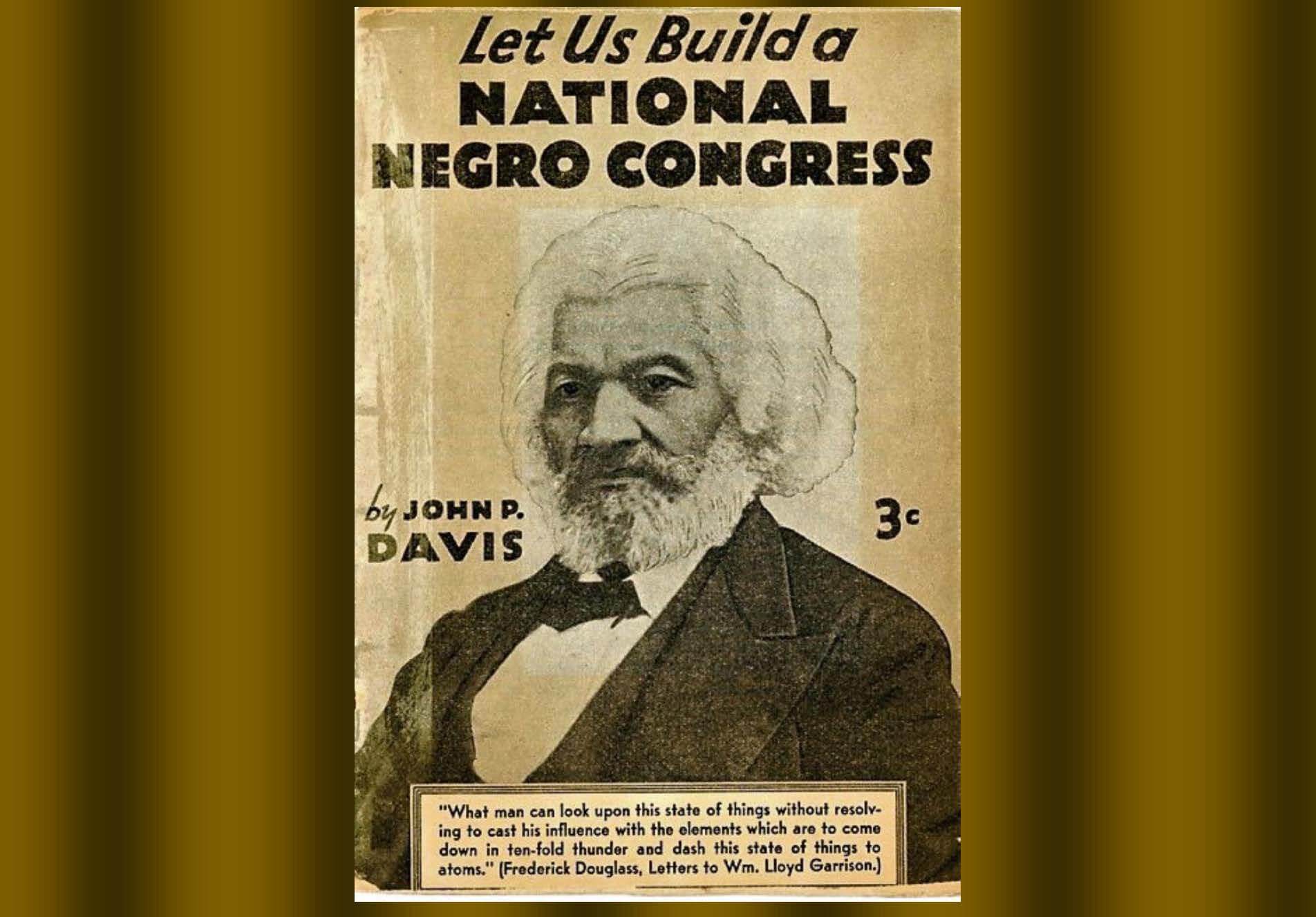

A. Philip Randolph, a prominent Black socialist and leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), was one of those who was dismissive of Communists’ beliefs and practices, which included regular Communist attacks on him and the leadership of his union. His attitude changed in the first half of 1935. Alarmed as well at the rise and spread of fascism, he came to respect CP members’ role in challenging New York City officials in the aftermath of a riot in Harlem in March 1935 and concluded that the united front the Communists were pushing might be an effective political vehicle. Putting aside his history of antagonism with the CP, he agreed to be the NNC’s first president and public face, while John P. Davis, a Harvard Law graduate close to the CP, served as its executive director. It was Davis, not Randolph, who ran the NNC’s daily operations. The article reconstructs the origins of the political rapprochement that brought the NNC into being.

Contemporaries and subsequent historians have offered a range of views about the NNC’s accomplishments and character. Some have depicted the NNC as a vibrant grassroots organization, a vanguard in the anti-fascist fight that included but was not dominated by Communists; it helped to “launch the first successful industrial labor movement” in the United States, and “remade urban politics and culture in America,” some contend. Others disagree with that picture. Social scientist and journalist Horace Cayton contended that the “Congress never became an organization supported by a membership but remained pretty much a paper front” whose policies were determined by the Communists and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, while Charlotta Bass, the editor of the California Eagle who would soon become a close ally of the Communist Party, noted the NNC’s “failure to achieve any outstanding accomplishment to racial progress.”

While my article doesn’t fully explore the NNC’s track record during the Popular Front years, it does argue that the organization was a genuine alliance of convenience that overcame past divisions and promised a new, militant political departure. Crucially, it also revisits the old question of the precise role the CP played in building and sustaining the NNC. It argues that while Communists did not control the NNC directly – at least initially — they were, in fact, the driving force in the organization during its early years. It suggests that historians who treat the NNC as something of an autonomous force in union and community campaigns downplay the Communists’ genuine contributions, withhold credit that actually belongs to party members who worked tirelessly under its banner. Recognizing the real if sometimes concealed role of CPers also allows us to better understand the steady undercurrent of criticism from anticommunist Black leaders, criticism that cannot be dismissed simply as misguided or opportunistic redbaiting.

Finally, the article argues that it is impossible to disentangle the organization’s transformation in 1940 from the issue of Communist influence. The Hitler-Stalin Pact (the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of Non-Aggression) of August 1939 brought an abrupt end to the Popular Front. Domestically, the CP put aside its antifascism and devoted itself to keeping America out of what it now called the inter-imperialist conflict in Europe. For the NNC, the matter came to a head at its third convention in late April 1940. John P. Davis offered unqualified support of the CP foreign policy line that “the Yanks Are Not Coming” while Randolph, refusing to stand for re-election, denounced both Nazi Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union as totalitarian societies. Delegates fled the auditorium as he spoke. Non-communists in attendance like Ralph Bunche, Layle Lane, and Pauli Murray had no doubt that the assembly was dominated by Communists, Black and white. To Murray, the Congress gathering was “a farce” that was “completely C.P. dominated” while Bunche predicted – with some exaggeration, that the membership would “soon be reduced to devout party members, close fellow travelers, and representatives of the C.I.O. unions.” The NNC survived the departure of Randolph and many other non-Communists and, in the months that followed, it dedicated itself to the CP’s anti-war stance. But the united front/Popular Front was dead.

While the NNC’s history “cannot be understood solely by reference to Communism,” as historian David Witwer once argued, downplaying communism – as many scholars have done — makes it harder to understand the organization’s formation and, later, its abrupt and dramatic change in ideological direction and the subsequent defection of non-Communist Black activists from its ranks. Rather than constituting a “hand grenade in debates about the Communist Party’s role in the Black freedom movements,” as one historian has recently put it, Communists and their actual relationship to the NNC are necessary components of any understanding of the organization’s rise and fall – or at least its rise and transformation into an organization whose membership and ideological orientation were indistinguishable from that of the CP. The NNC’s history cannot be told without wrestling with the “hand grenade” of the Communist issue.

Above: In the pages of his union journal, The Black Worker, A. Philip Randolph, the president of both the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the National Negro Congress, explained in forceful terms why he had left the National Negro Congress. The organization, he argued, had lost its independence; it had come to depend on the CIO and the Communist party for its funding and had come under communist domination. “I consider the Communists a definite menace and a danger to the Negro people and labor,” he made clear, ‘because of rule or ruin and disruptive tactics in the interest of the Soviet Union.” He had quit the NNC, he explained, “because it is not truly a Negro Congress.” Credit: The Black Worker

1 Comment

Comments are closed.