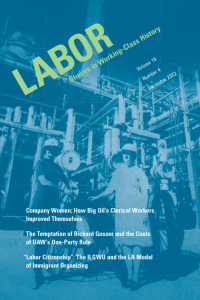

The new issue of the journal Labor: Studies in Working-Class History is out, and we are pleased to move Sara Stanford McIntyre’s essay from behind the paywall for three months, thanks to Duke University Press. The essay reveals that women were part of the early oil industry, if in a conflicted position. We asked the author to provide a wrap around introduction with additional photos. –Editor

Desk and Derrick was a female-only petroleum industry employees’ club, founded in 1947. Uncovering the club’s hidden history emphasizes the importance of women – white women who largely made up the industry’s clerical and support staff — to the development of the twentieth-century American oil industry.

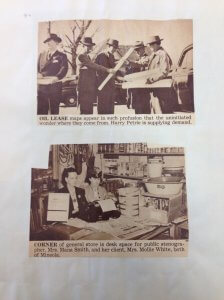

The American oil industry has long cultivated its own mythology of rugged masculinity — lone-wolf inventors and lucky wildcatters who prospered through grit, determination, and sometimes divine intervention. Especially before the 1970s, women were supposedly nonexistent in the labor of producing oil. Oral history informants, industry periodicals, and local newspapers all attest to the absence of “respectable” women from the streets of oil towns and from the payrolls of the quickly growing ranks of oil companies. However, while it was true that the most employees were men — industry jobs required extreme physical strength and that crews worked long hours in isolated locations — a complete absence of women was more aspirational than representative of reality. For example, the below newspaper clipping from 1941 depicts an industry stenographer taking notes during a lease contract agreement.

In contrast to the lonely, romantic picture presented in the industry’s collective memory, oil experienced many of the same upheavals facing other large-scale scientific and engineering enterprises during the middle decades of the twentieth century. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, oil’s white collar and administrative jobs expanded rapidly. And, as in other industries, women were fundamental to oil industry technological development and labor conflicts. Anxieties about changing workplace hierarchies, prestige, manhood, and the changing meaning of success were reflected in oil industry publications, pageants, civic events, and advertising.

Prostitution and the sex trade were common in many oil towns and industry celebrations regularly provided women for the male gaze. This continued into the post-war era. For example, the 1952 cover of the Odessa American, daily paper for the oil city of Odessa, Texas, advertised the latest oil trade show, headlined by “local high school bathing beauties posing with the world’s largest vat of baked beans.”

In contrast to both historical erasure or overt sexualization, Desk and Derrick’s was a haven for credentialed women, providing community, training, and leadership opportunities in an industry deeply hostile to female employees. The club provided numerous outreach and educational campaigns included seminars, workshops, fieldtrips, and conventions. For example, in this 1950s photo, members of the Odessa, Texas D and D chapter attend a fieldtrip excursion at an oil refinery. They then submitted photographic proof of their trip to the company magazine, the TP Voice.

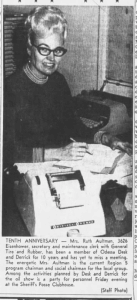

Such an image showcased female competence and technical interests, clashing with derision displayed in the pages of union periodicals or their absence in most other company publications. The club maintained a vocal emphasis on scientific education and credentialization, two things that represented a bid for female inclusion within an increasingly technically complex professional world. To this end, the club regularly sent press releases honoring the work of local members. For example, the Odessa chapter of D and D submitted the below photo in the Odessa American, honoring Ruth Aultman, a secretary with General Tire and Rubber Co. for her ten years of service to the club.

Although the presence of a large white-collar workforce in the oil industry was decades-old by 1970, such images and such public acknowledgements remained rare in oil cities and towns.

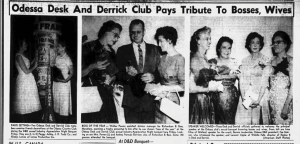

Despite the club’s many efforts, entrenched workplace sexism and union hostility to changing labor structures limited member opportunities. Few women worked in the most lucrative or prestigious oil industry jobs and often their desire for careers were perceived as indicative of selfishness. More broadly, fundamental questions remained as to how women who worked outside the home could reconcile their desire for professional advancement and individual recognition without invalidating the importance of women who chose a different path. Some chapters attempted to explicitly bridge such divides. For example, in 1960 the Odessa chapter of D and D hosted an “Industry Appreciation Night” banquet and distributed award to both the bosses of local oil companies and their wives for their service to the industry.

Such a banquet attempted to make visible the unacknowledged and uncompensated labor of homemakers, equating it in prestige and importance to the work of an oil company boss. Further, in an era when secretarial and clerical staff were regularly lampooned as supposedly sexually available for their bosses, such overtures and efforts at solidarity and recognition were pointed.

Ultimately, such efforts remained partial at best. Desk and Derrick’s middle-class aspirations allied the club with industry rebranding efforts that supported industry automation and union-busting. Desk and Derrick valorized industry engineers and scientific professionals, spreading narratives of prosperity through technology that coincided with industry-wide efforts to repair oil companies’ reputations as greedy, wasteful, and exploitative. In turn, mid-century oil companies promoted Desk and Derrick as a convenient, grassroots way to spread their message. While the club remains active in the industry to this day, it continues to reflect the conflicted place of women in the industry.