This essay initiates our Symposium on Tom Alter’s new book, Toward a Cooperative Commonwealth: The Transplanted Roots of Farmer-Labor Radicalism in Texas, published recently by University of Illinois Press. Contributions by Theresa Case and Chad Pearson as well as a response by Tom Alter will be published as well. Thanks to Chad Pearson for organizing this symposium. These are peer-reviewed.

The last dozen years has seen a minor boom in scholars’ studies of the early twentieth century Texas Socialist Party and the people who cast ballots for it. Among the offerings are two monographs, a biography and a few articles. These recent works, taken together, along with an older study by Neil Foley, constitute a growing harvest of tribute to the late James R. Green and his foundational Grass-Roots Socialism: Radical Movements in the Southwest, 1895-1943 (1978). For those beginning a foray into the Debsian heyday of the socialist movement in Texas, Thomas Alter II’s Toward a Cooperative Commonwealth: The Transplanted Roots of Farmer-Labor Radicalism in Texas is the first place to begin. For my money, reading Alter’s new work improves a reading of Green as well as the recent works.[1]

After Green’s densely packed study of early twentieth century Socialists in the “Old Southwest” — Oklahoma (mainly), Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana – it would be twenty-one years before the arrival of Foley’s White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture (1998). Building on the popularity of “whiteness” studies, Foley examined the racial tensions within the political economy of corporate cotton production in early twentieth century South Texas and included a chapter on the Texas Socialists. Foley found the Texas Socialist Party failed to live up to its own ideology regarding equality. The Texas Socialists’ chief representatives may have stirred up the rural white populace, but he found they were stubbornly slow to reach out to the state’s Mexican American agricultural workers and never reached out to African Americans. Quite the opposite: Foley wrote that Hickey evinced a “crude racism” worthy of any status quo politician.[2]

Another decade passed before the current boomlet began with my Yeomen, Sharecroppers and Socialists: Plain Folk Protest in Texas, 1870-1914 (2008). With much space devoted to work, religion and community, this cultural history of those who voted for socialism included a chapter on the plain folk religious basis of Socialists’ critique as well as a chapter on the Texas Socialist party. My goal was to discover whether component parts existed within rural poor people’s culture that Socialist agitation could have catalyzed. I found most white rural poor people hopelessly committed to white supremacy as well as to the absolute right of private property; yet, my argument was that a remnant of the rural Southern poor had available a religion-based critique of capitalism as wicked, and exploitative, creating unearned wealth for landlords, merchants and bankers from the sweat of impoverished sharecropper families. An even smaller minority came to a rational and moral rejection of white supremacy in favor of a cooperative commonwealth.[3]

In Yeomen, Sharecroppers and Socialists I sought to understand the culture of Socialist voters in Texas by concentrating on the rural poor, specifically white and black small farmers, owners and sharecroppers, who made up the overwhelming majority in the 83 counties of East Texas and the Blackland Prairie where I focused my study. I sought to discover the bridge between historians’ past descriptions of the Southern poor majority (ignorant, passive, fatalistic, and incapable of analysis, governed by racial animus) and a remnant’s support for class-based analysis. Historians ground their view of rural poor Southerners in the pervasive adherence to white supremacy along with religious denominations that served the interest of the status quo. There is truth in that assessment, as my research confirmed, but it ignores the historic struggle launched by dissidents from among the rural poor against this power structure. It ignores the fact that rural Texans voted for Socialism at two-and-a-half times the rate of voters in Texas towns and cities.[4]

While the Texas religious establishment threw the considerable weight of pulpits, denominational organs and hierarchy into the fight on behalf of white supremacy and capitalism, a remnant of poor people’s rural churches and their preachers broke ranks in favor of a cooperative commonwealth. Like James Bissett’s outstanding work on Oklahoma, I found Texas Socialist preachers coming from the rural poor people religions of Holiness and Church of Christ as well as some Methodists and Baptists.[5] A minority of poor people’s organic intellectuals, preachers and rural newspaper-writers, challenged their audiences to imagine a future different from their present or past. On the other hand, most of this class of rhetoricians, cleaved to the party, white supremacy and god of their fathers. No amount of hopeful attention to remnants should obscure the choices of the majority. In the end, adherence to white supremacy and belief in private property triumphed over class-consciousness among the shrunken post-poll tax Texas electorate.

Thereafter the pace quickened with more works appearing on people or aspects of the movement. In his biographical article on Texas Socialist gubernatorial standard-bearer Reddin Andrews, Keith L. King puts the Andrews family in the religious context of their times. Andrews trained as a Baptist minister, graduating from Texas’ Baylor University and a Baptist seminary in South Carolina. King sees Andrews’ activism as fulfilling the positive role of safety valve, venting the rural poor’s resentment about the march of modernity. King sees the extended Andrews family as exemplars of agrarian protest as represented by rural Southern Baptists. He argues that Reddin Andrews and his kin saw no contradictions between the doctrines of “the Baptist Church” and the teachings of Socialism. Steeped in Southern Baptist education and serving numerous country pastorates and even a term as president of Baylor, the Stetson-wearing Andrews had the cultural credentials to be a “true Texan.” Andrews seems to embody the “alternative South” for some and a safety valve for others.[6]

In “Smith County Socialists, 1900-1918” Vicki Betts increases our understanding with fine local detail often missing from statewide studies. Concentrating on one East Texas county, Betts details the people and rural communities that supported the Socialist cause. The county seat of Tyler was hometown to two important Socialists, Party Secretary W. J. Bell and the head of the 1910 and 1912 ticket, gubernatorial candidate Reddin Andrews; yet their presence did not result in town-based support for this overwhelmingly rural party. During the peak Socialist elections, Betts finds the same rural-town divide in the piney woods that I found on the cotton-dominated blackland further west. In both cases, the vast majority of Socialist votes came from farming precincts. Further, in “The Consequences of Dissent in East Texas, 1917-1921,” Betts documents World War I-era suppression of the Texas Left. Locals helped the Federal Government round up two dozen rural Socialists and courts quickly convicted them of the new Sedition Act and shipped them off to federal prison. Other East Texas patriots rounded up a small group of their Socialist neighbors stripped and lashed them with a “blacksnake whip,” poured salt into their torn flesh and ran them out of town.[7]

In Red Tom Hickey: The Uncrowned King of Texas Socialism (2020), a splendid biography of editor, orator and candidate Thomas A. Hickey, historian Peter H. Buckingham explores the life of the most visible representative of the Texas movement. Born in Dublin to Irish nationalists and raised on anti-landlordism, upon arrival in the US the immigrant Hickey organized for the Socialist Labor Party and the Industrial Workers of the World in the North and Southwest before landing in Texas. There he found backing for a statewide Socialist newspaper from Lavaca County’s Meitzen family whose transnational sojourn Thomas Alter documents. As his subtitle suggests, Buckingham sees Hickey as the linchpin to understanding the Texas Socialist movement’s brief success. Hickey was flawed but stalwart, committing his extraordinary energy and rhetorical talents to the cause of the Texas Socialist Party, the Renters’ Union and, eventually, the Nonpartisan Land League. No exploration of Southwestern radicalism can be complete without communing with Buckingham’s deeply researched and beautifully written Red Tom Hickey.[8]

Thomas Alter’s masterful Toward a Cooperative Commonwealth is the new starting place for students of Southwestern Socialist voting in the age of Debs. Even Green’s foundational Grass-Roots Socialism gives scant attention to the radical “’48-ers,” I completely ignored transnational influences from the Central and South Texas Hill Country Germans in my focus on the traditional Southern poor whites and African Americans in North Texas. This more than corrects my omission. Alter’s sweeping narrative, beginning in the early-nineteenth century Prussian province of Silesia, demystifies much of the Texas vote for Socialism by demonstrating conclusively the democratic socialist traditions some immigrants like the Meitzen family brought with them onboard the ships to Galveston. Alter’s clear writing and well-argued analysis provides students of the Texas Socialist movement a newly congruent foundation. To repeat, this is the book to read first.[9]

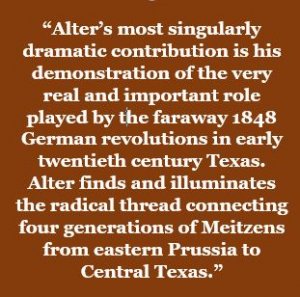

Alter’s most singularly dramatic contribution is his demonstration of the very real and important role played by the faraway 1848 German revolutions in early twentieth century Texas. Alter finds and illuminates the radical thread connecting four generations of Meitzens from eastern Prussia to Central Texas. He provides clear analysis of the Socialist intraparty fight between centralizers and decentralizers, orthodox Marxist collectivists and the anti-collectivist small farmers of Oklahoma and Texas. Finally, Alter provides denouement, tracing the Meitzens’ “descent into New Deal liberalism.” For the most part, Alter sees the Meitzens generally swimming upstream against the current of Texas white supremacy while acknowledging their failings in that regard.[10]

Racism and white supremacy is at the heart of seeking to understand early twentieth century Texas politics. Foley sees in Irish-immigrant Hickey and the Texas Socialist Party another failure of poor whites to overcome their self-defeating white supremacy. While I agree with Foley’s understanding of the persistence of white supremacy across the board for Texas whites, I tend to agree with Green, Buckingham and Alter in seeing the Texas Socialists struggling – sometimes feebly – against their own racism or that of the dominant culture in a spotty effort to embrace the class-based analysis of the international socialist movement. In the political universe of early twentieth century Texas among actual political parties available – the avowedly white supremacist Democrats, the, by then, “lily-white” Republicans, the explicitly racist Prohibitionists and the Socialists – only the Socialists claimed to explain growing landlessness and poverty as class-based exploitation and not racial hierarchy. Spokespersons for the ruling class – the establishment pulpit and press – singled out the Socialists for continuous attacks as racial traitors. Unfortunately, their critics were not always right. The message of the American Left – everywhere — was consistently weakened by individuals whose racial beliefs were more American than Socialist.

The debate among historians of rural radicals tend to revolve around whether or not the dissidents in question were forward-looking “true” socialists (or true radicals or true liberals, depending on the historian), or, were they, instead, a backward people bound by their ignorant traditions and racist culture with nostalgic dreams of a better Jeffersonian past. To what degree were the rural poor whites of the late 19th and early 20th century able to cut the millstone of white supremacy from around their necks? The answer is blindingly obvious whether from the perspective of a radical cooperative commonwealth or a liberal capitalist society: not nearly enough. In Alter’s view, the Meitzens walked a cultural tightrope caught between the antiracist promise of Socialism’s class consciousness and the obviously deep racism of the people they were trying to convert.

Texas social and political movements would be better understood if they were analyzed as part of a larger regional or national whole. James R. Green made a start in this direction by looking at Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana. Nevertheless, there remains the need for a study of southern Socialism, or a nationwide study of American agrarian radicals which could duly account for the various regions of the country. Indeed, there are still no histories of state Socialist parties for most of the southern states.

Green sees Texas Socialism as a Midwestern import into Texas by way of Debs’ Social Democracy. Buckingham sees another transplant — Hickey — as the key to understanding Texas’ brief flirtation with radicalism. And the Meitzens’ brought their social conscience from Silesia in the 1850s. But, a majority of the rural Texas poor people who voted Socialist were either responding to Hickey’s or Debs’ superior persuasive abilities, or continuing old family traditions of radical dissent, then there’s not much left to explain about rural Texans voting for the Socialist Party.

If the Hill Country voted for the Socialist party because of the long influence of the 1848 radicals, how does one explain similar votes in Northeast Texas with its small to nonexistent German population? That is, what is the significance of early twentieth century poor Southern voters (mostly white after the disfranchising poll tax of 1902) voting Left? If Texas Socialist votes in the 1910s can be explained by showing that Texas rural voters were atypical, legatees of Texas’ unique revolutionary Germans, then the Texas experience will not prove much of a guide to understanding the movement elsewhere. But, if some of the raw material for a radical critique actually already existed in the culture or religion of the Southern rural poor, then the Meitzens and others may be seen as critical catalysts, sparking something already there, rather than the cause of such a critique.

Of course, whether poor white, African American or German, nobody’s culture was a fixed commodity. External factors acted upon cultures regularly. Witness the rise of Left journalism in the Southwest led by The Appeal to Reason and The Rebel but augmented by dozens of local, short-lived Southwestern Socialist newspapers. The radical newspapers, agitators and organizers were the spoons; the misery of the cotton patch with spiraling tenancy rates and exploitative landlords was the batter.

All of these studies lie outside the mainstream of Texas historiography. That school sees the early twentieth century as a time of growing prosperity in the cotton towns and county seats of Texas. Instead of exploitation, poverty and violent white supremacy, this school sees in the early twentieth century a path toward prosperity and growing economic opportunities, a dying down of violent white supremacy, and a strengthening of law and order.[11] For example, Texas’ cotton crop came to eclipse that of all the other Southern states and did indeed create widespread prosperity among larger landowners and town-based landlords as well as the subsidiary industries of gins, compresses, warehouses, banks and railroads. Like other agricultural economies during times of rapid change, the nature of that change might look different depending on whose experiences historians interrogate.

When looking at the poor majority in Texas, the early twentieth century picture is one of poverty and lack of opportunity. In 1880, two-thirds of Texas farmers had owned their own farms. By 1910, a majority of Texas farmers were farming someone else’s land. They need not have read Marx to be disappointed and angry. Some among the rural poor’s organic intellectuals led a multi-generational rebellion against these agricultural hard times from the 1880s until the New Deal. Thomas Alter’s Cooperative Commonwealth: The Transplanted Roots of Farmer-Labor Radicalism in Texas is an essential contribution to understanding that process. Readers will be hard-pressed to find a better introduction to the topic.

[1] James R. Green, Grass Roots Socialism: Radical Movements in the Southwest, 1895-1943 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978); Thomas E. Alter II, Toward a Cooperative Commonwealth: The Transplanted Roots of Farmer-Labor Radicalism in Texas (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2022).

[2] Neil Foley, White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 99-105.

[3] Kyle G. Wilkison, Yeomen, Sharecroppers and Socialists: Plain Folk Protest in Texas, 1870-1914 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2009).

[4] Wilkison, Yeomen, Sharecroppers and Socialists, 196.

[5] James Bissett, Agrarian Socialism in America: Marx, Jefferson and Jesus in the Oklahoma Countryside, 1904-1920 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999).

[6] Keith L. King, “Reddin Andrews and his Family: Agrarian Radicalism in Central Texas,” Central Texas Studies, III, (2018); I see Andrews as one of Gramsci’s “organic intellectuals” who, in spite of his professional training, never identified his mission with the needs of the capitalist system; On Andrews’ appearance, see Green, 121; For reflections on the contentious notion of “true Texan,” see Ty Cashion, The Lone Star Mind: Reimagining Texas History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018), 33, 46, 77, 159, 166 and 192.

[7] Vicki Betts, “Smith County Socialists, 1900-1918,” Chronicles of Smith County, Texas (2014) pp. 8, 11, 14-18. ; Wilkison, Yeomen, Sharecroppers and Socialists, 196 and 201; Betts, Socialists, 13-14; Vicki Betts, “The Consequences of Dissent in East Texas, 1917-1921” (2018), Presentations and Publications. Paper 57, 115-121 (The University of Texas at Tyler, Scholar Works at UT-Tyler); for more on wartime repression of the Texas Socialists, see Steven Boyd and David Smith, “Thomas Hickey, the Rebel, and Civil Liberties in Wartime Texas,” East Texas Historical Journal [2007] Vol. 45:1, Article 12.

[8] Peter H. Buckingham, “Red Tom” Hickey: The Uncrowned King of Texas Socialism (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2020).

[9] Alter, 31-36.

[10] Alter, 171-218.

[11] Walter Buenger, Path to a Modern South: Northeast Texas Between Reconstruction and the Great Depression (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001).