The new issue of the journal Labor: Studies in Working-Class History is out, and we are pleased to move Janet K. Weaver’s essay from behind the paywall for three months, thanks to Duke University Press. It’s an essay on a young Iowa woman who tried to make unions a force for change more than a hundred years ago. Janet Weaver has written this introduction to the essay’s themes, with some beautiful photos to accompany it. She shows how relevant the issues that young workers faced then are to this current upsurge in organizing. –Editor

Young workers today are leading a surge in unionization campaigns at traditionally anti-union strongholds like Amazon and Starbucks. The question these workers raise for today’s labor movement, says Association of Flight Attendants international president Sara Nelson, is whether it can keep up with them.

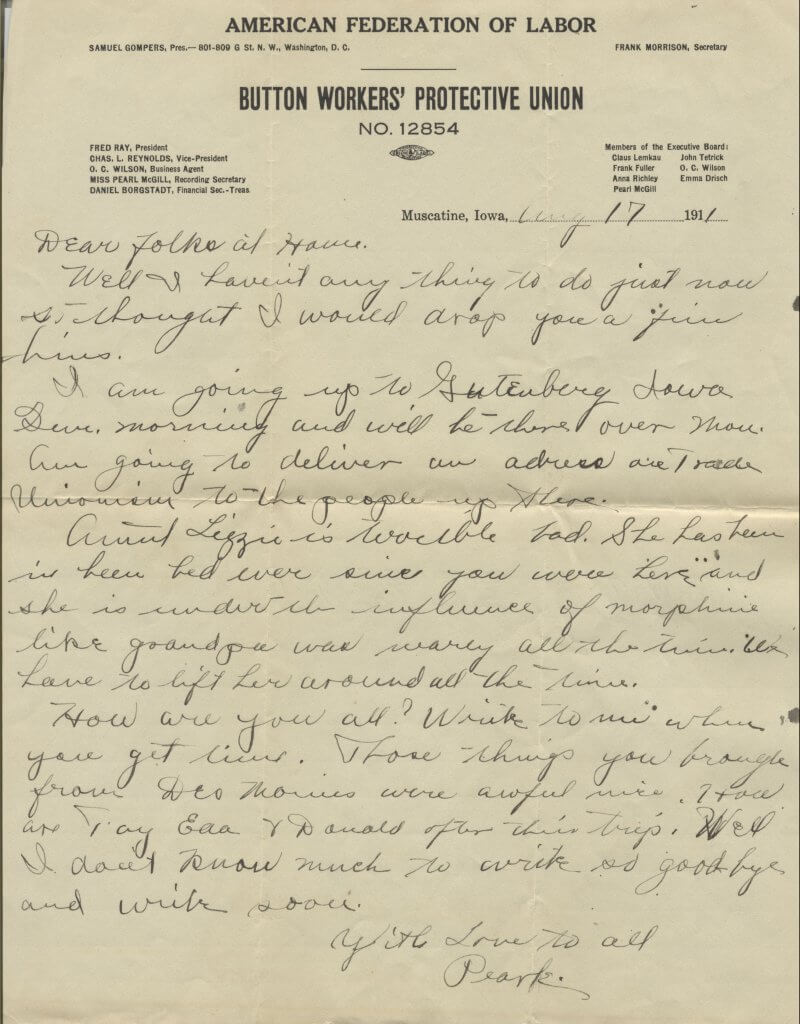

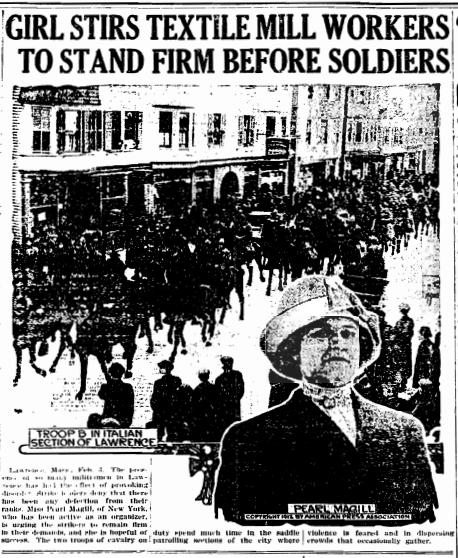

Nelson’s observation takes us back to an earlier upsurge of youth-led organizing campaigns during the Progressive Era. These proliferated as workers across the country rose up against almost insurmountable odds to demand the right to decent wages and working conditions through inclusive unionism. As young women filled low-wage jobs in burgeoning industrial sectors, their enthusiasm for inclusive unionism was part of a vital impulse that swept the country. That impulse propelled the uprising of women workers in the garment industry in New York and Chicago in 1909 and 1910, the textile industry in Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1912, and the button industry in Muscatine, Iowa in 1911. In these industries women emerged as leaders in what 17-year-old Iowa button worker and union leader Pearl McGill described as a “big fight for justice.”

Pearl McGill is emblematic of the many youthful voices of wage-earning women activists and militant labor leaders that rang out across the country. Like McGill, most of these women did not find a career path open to them through established labor institutions of their day and returned to unexceptional careers as teachers and housewives, largely disappearing from historical memory. A few, like McGill, left traces on the historical record that upend our understanding and interpretation of the events they helped shape.

In “The Road Not Taken,” in the latest issue of Labor, I argue that the radical unionism of Pearl McGill straddled two union cultures: those of inclusive unionism and of the AFL. Her support for inclusive unionism was rooted in her experience in Iowa. But it was also part of a longer tradition of early struggles for a living wage and workplace rights through collective action that pushed the boundaries of the exclusively white, male, and craft-dominated AFL through the Knights of Labor and federal unions. When McGill actively participated with the IWW in the Lawrence strike, she confronted the limits of the AFL’s trade unionism. Her role in the strikes of button workers in Iowa and textile workers in New England shines a light on the ways in which grassroots activists invested hope that AFL “federal labor unions” (local unions directly affiliated with the national AFL) might serve as a vehicle for their inclusive union aspirations. Her contribution enhances our understanding of the limitations of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) and the contested terrain of ethnicity and gender on which its leaders sought to organize women factory workers, constrained as they were by their loyalty to the AFL.

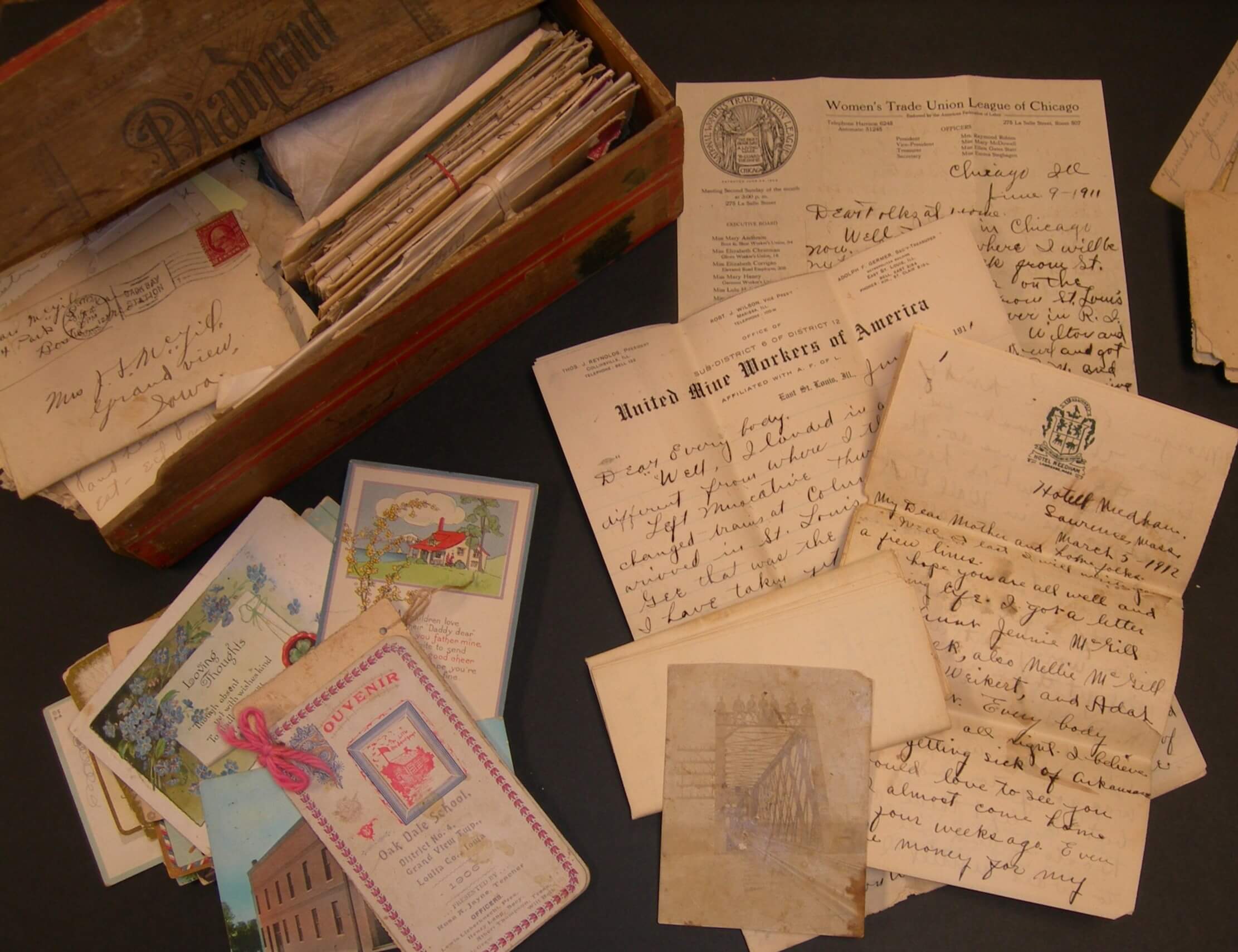

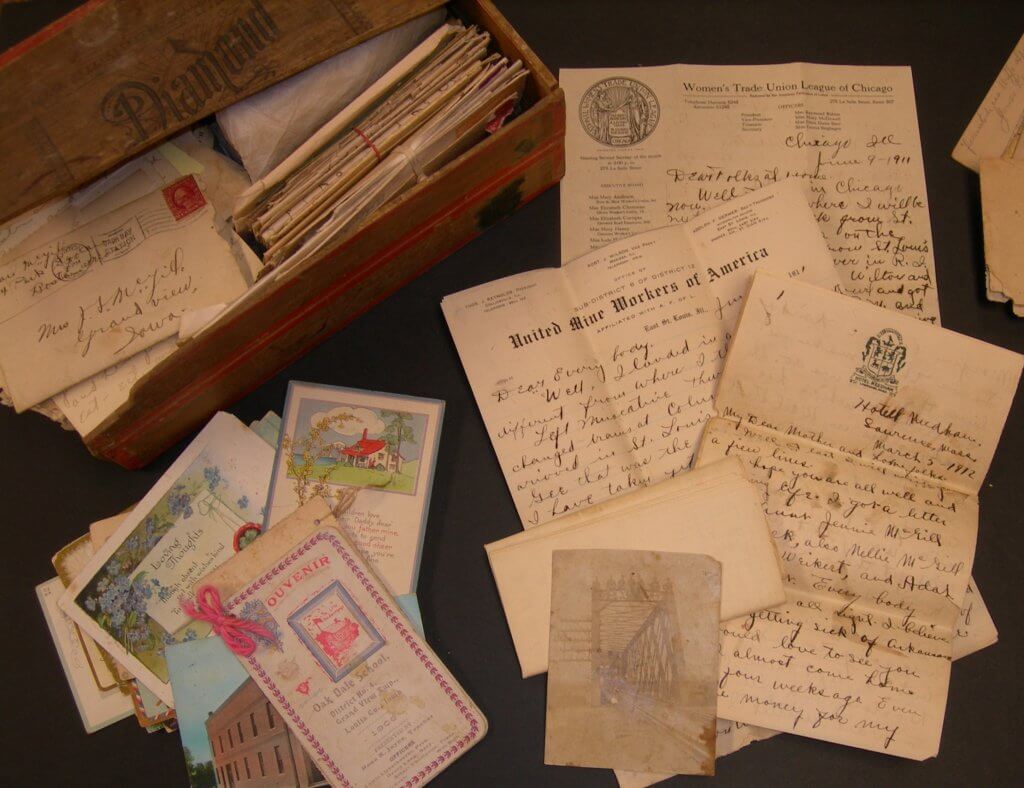

McGill’s letters demand a broader examination of the relationship between the craft-dominated AFL, its affiliated WTUL, and the grassroots efforts of young women and new immigrants to build more inclusive unions. Her letters provided a trail that led to the records of the WTUL, the AFL, and underutilized newspapers sources in New England. These records revealed not only that McGill was a prominent leader assisting textile workers in Lawrence to organize under the AFL’s rival – the Industrial Workers of the World – but also that she had assumed a leadership role in other IWW-led strikes throughout New England. Whether in Iowa or New England, McGill never adopted the nativist rhetoric and sentiments prevalent among some WTUL and AFL leaders but instead remained consistent in upholding the broad-based principles of inclusive unionism she had learned in Iowa.

McGill’s parents might well have seen their 17-year-old daughter featured prominently in this article in the Chicago Daily Socialist. A month later she wrote:

Well, at last I will write you a few lines. … There is a big war being fought here. A battle for bread and a battle for life. The little children of the textile workers were examined by twelve N.Y. Doctors, who said that they were suffering from malnutrition. That means that they were like a plant which had grown in the shade. They had never had enough to eat, or the right kind of a livelihood to give them health, and they were undersized, under weight and all the rest.

. . . And here is why I love the fight. Because this capitalist government has kept me where I am, in the factory, out on strike, out of school, and out of work and can’t get a job. Yes, this is free America, but as long as I live people will know something about the class war, unless it is settled before I die, and I would die for the just cause of starving out of work people in my nation, the working class if necessary. Maybe you think I am losing my mind, but I have just lately come to my senses ….

When connected with rich local history narratives such as that of the button workers of Muscatine, a fresh look at the institutional history of the labor organizations of this period reveals that the AFL’s eventual dominance resulted from a less certain and more contingent trajectory. The vulnerability of elite craft unions in the AFL (epitomized by the older, male-dominated craft unions in textiles and steel) comes into better focus as the full force of new mass production technologies swept the country and a new generation of radical, youthful semiskilled and unskilled mass production workers rose up to demand their rights.