Karen Sieber tells us of the effort to honor the memory of slain union organizer Ella May Wiggins and the struggle for power by textile workers in the South.

The city of Gastonia, North Carolina, has grappled with how to remember the Loray Mill Strike of 1929 for decades.

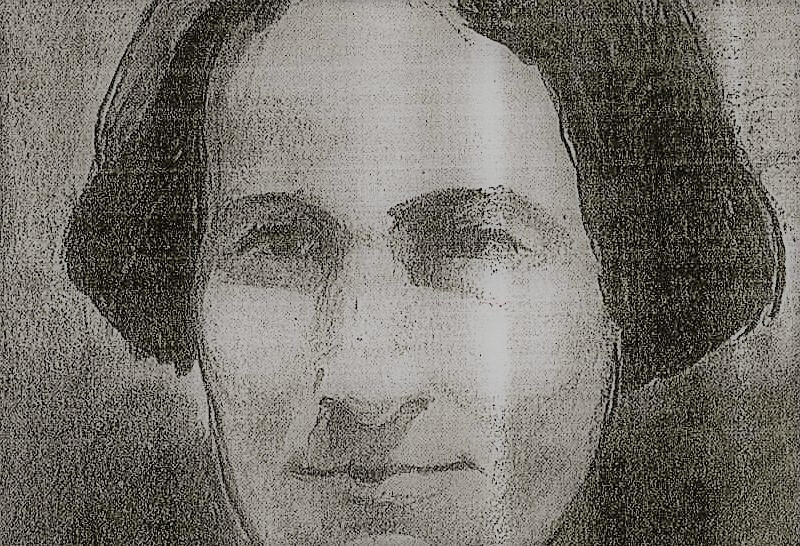

Although the strike was ultimately unsuccessful, controversies surrounding the conflict drew the nation’s attention to the plight of textile workers, and helped spark a labor movement throughout the south which led to the creation of the United Textile Workers Union in the 1930s. In particular, the mob attack and murder of Ella May Wiggins, a pregnant mother of five who was a mill worker, union organizer, and balladeer, spurred the movement to continue beyond Gaston County. For the enemies of unionism, the death of Police Chief Orville Aderholdt during an altercation with strikers provided similar fuel.

When the state first proposed to erect a historical marker about the strike in 1986, the plan was squashed due to disagreements over text. Gastonia officials wanted to eliminate any mention of deaths, and add wording about local citizens defeating “the first Communist efforts to control southern textiles.” While a marker recognizing the strike was eventually erected in front of the then-abandoned mill in 2007, the wording remained problematic, reading: “A strike in 1929 at the Loray Mill, 200 yards S., left two dead and spurred opposition to labor unions statewide.” In addition to only highlighting opposition to the unions, the inscription is devoid of human actors, fails to mention the reasons for the strike, and ignores the strike’s significance within American labor history.

Thankfully, a group called the Ella May Wiggins Memorial Committee has been raising funds to erect a statue devoted to the martyred union organizer and songstress. While they had initially looked into Gastonia locations, the plan now is to erect the statue in nearby Bessemer City, North Carolina where Wiggins resided and worked.

Even though she was never employed at the Loray Mill, she knew firsthand why workers down the road began organizing in the spring of 1929. Like many, she worked long hours doing tedious mill work and still struggled to provide for her family. At not even thirty years old, she had already lost four children due to lack of nutrition or health care. After her husband abandoned her, Wiggins, who was white, relied on the help of other mill workers in her Bessemer City community of “Stump Town” which was largely African American.

Countless sharecroppers and subsistence farmers from throughout the Piedmont, Appalachia, and beyond like Wiggins were recruited by agents promising them a better life in Gastonia, known as “Spindle City.” At over a half million square feet, the Loray Mill was the epicenter of the local textile industry, but smaller mills like the one Wiggins worked at dotted the landscape surrounding the town. The mill’s early success relied upon entire families who were employed in the mill and lived together in the mill village. Lewis Hine would famously photograph child laborers at Loray in 1908.

Business boomed for a while, but when the Rhode Island-based Manville Jenckes Company took over the mill in 1923, they implemented what was collectively known as “stretch out measures” which included longer hours, wage reductions, piecework, the installation of hank clocks to track productivity, and other tactics that stretched employees even thinner for a profit. Employees, including Wiggins, would leave poor conditions at one mill only to find similar conditions elsewhere. Due to the nature of mill work, female employees were affected more than men by these measures.

The massive size of Loray’s workforce, and the fact that Gaston County had more spindles in operation than any other county in the South at the time, convinced the Communist party-led National Textile Workers Union (NTWU) to use the mill as a test case for larger union organization efforts throughout the South in 1929. The workers staged a walk out on March 31, 1929, with a general strike called the following day. Their demands were simple: recognition of the union, a 40-hour work week with at least a $20-a-week wage, equal pay for men and women, and the removal of hank clocks. Many in the NTWU, including Wiggins, also argued for equal pay for Black and white workers, which further angered many in the South.

North Carolina Governor O. Max Gardner, himself a mill owner, called in the National Guard to quash these initial efforts, and the mill reopened. When strikers persisted, mill owners booted many from their company-owned mill village housing, forcing them to join a growing tent city along Franklin Avenue. By the summer of 1929, the NTWU recruited workers at mills throughout the region to build on the momentum started at the Loray Mill.

Wiggins left her job at American Mill No. 2 to work in organizing and bookkeeping for the Bessemer City NTWU branch. She also used her skills as a songwriter to help the effort, writing easy-to-learn ballads set to familiar mountain folk songs that she performed at meetings, often with her kids in tow. Woodie Guthrie would later call her “the pioneer of the protest ballad.” Her most popular song, Mill Mother’s Lament, put into words her own troubles with making ends meet as a spinner.

Excerpt:

We leave our homes in the morning,

We kiss our children good bye,

While we slave for the bosses,

Our children scream and cry.

And when we draw our money,

Our grocery bills to pay,

Not a cent to spend for clothing,

Not a cent to lay away.

Local officials feared just how quickly the union, and the tent city, were beginning to grow. On June 7, 1929, the police were called to the union headquarters in the tent city, and Sheriff Orville Aderholt was shot in a dispute. His death fueled violent anti-Communist and anti-union attacks throughout the summer. In early September, a mob ransacked the tent city and union headquarters, and dragged union leaders out to the woods to attack them.

On September 14, 1929, Wiggins and fellow union members from Bessemer City were riding in the back of a pickup truck when their vehicle was surrounded and then attacked by a mob firing upon them. She died at the scene. The story quickly made national headlines, accompanied by photos of her orphaned children. On the day of her funeral, hundreds of mills across the region announced one-day strikes in solidarity.

Locally though, the strike never recovered from Wiggins’s death. Less than two weeks later, the union abandoned the effort and asked the remaining tent colony residents to disperse. Mill owners never met the strikers’ demands, and many of those who participated were blacklisted from working at many other local mills. Unions never did again gain a stronghold in the city.

In many ways, erecting a statue honoring Wiggins’ bravery and sacrifice in Bessemer City rather than in Gastonia makes sense. For it was not only where she lived and worked, but separating the memorial from the institution itself highlights the universality of her story, and her songs, that could be felt by workers at mills throughout the region. By keeping her story alive, it keeps alive the story of the countless nameless overworked and underpaid poor rural Appalachians who flocked to mills like the Loray in search of a better life never found.

For more on the Ella May Wiggins Memorial Committee, visit https://ellamaywiggins.com/.

Credit: Ella May Wiggins Memorial Committee