“The obrera recognizes her rights, proudly raises her head and joins the struggle, the time of her degradation is over, she is no longer a slave sold for some coins, she is no longer a servant, but the equal of a man,” wrote Texas border native Jovita Idar in 1911.

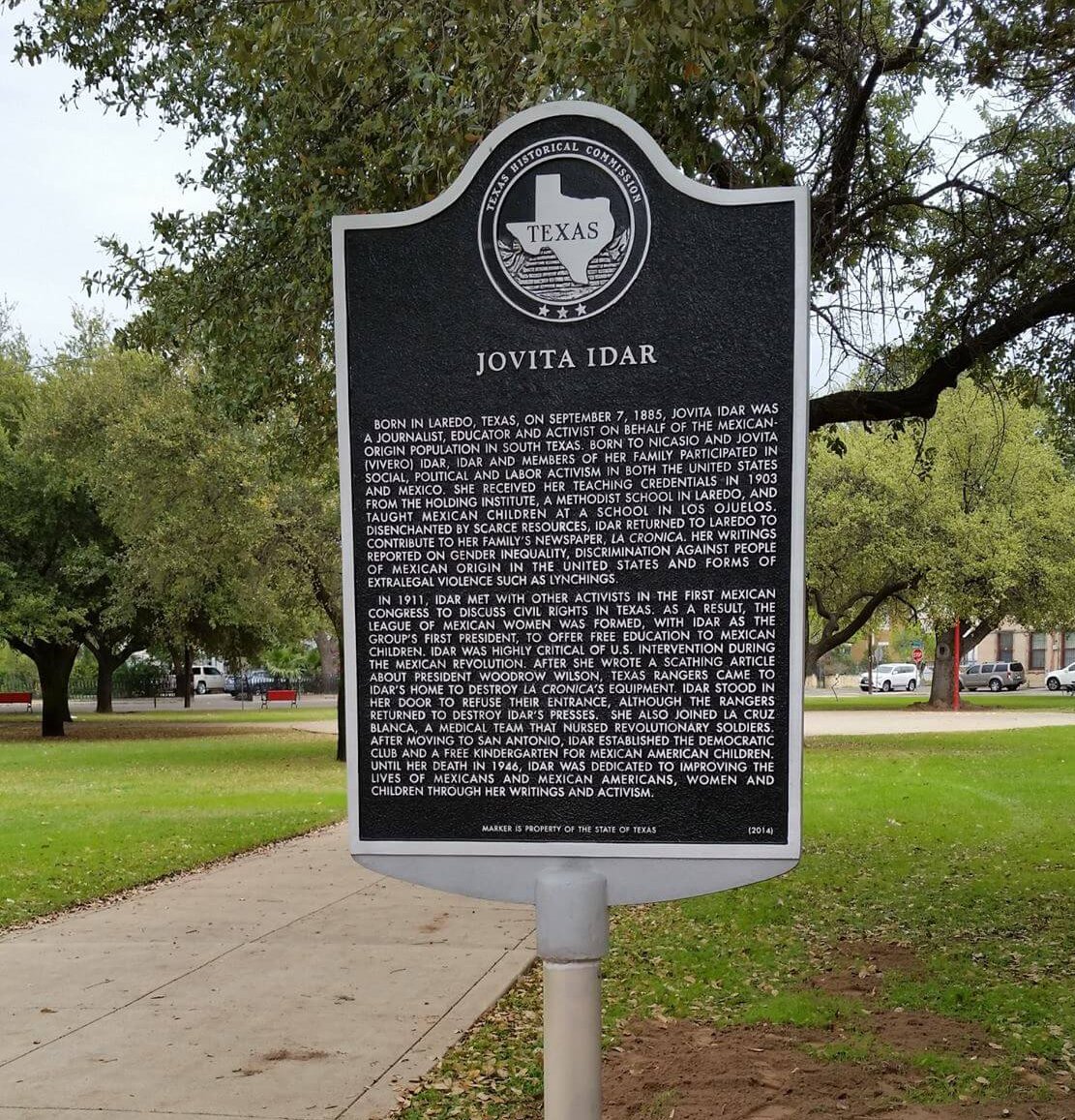

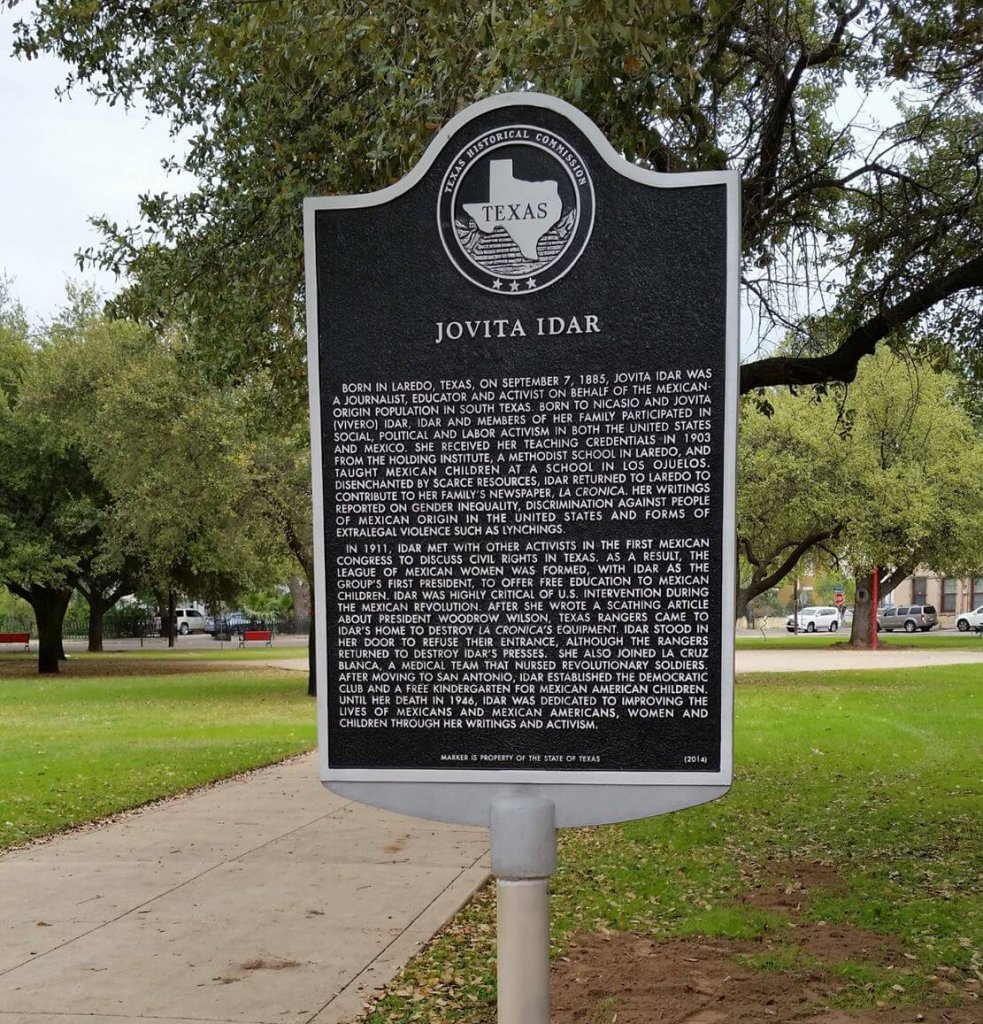

Until very recently, Jovita Idar remained a presence only in some people’s memories and in the occasional historical publication. But historical analysis need not be confined to monographs and journal articles. Rarely does the larger public engage with such publications. Recognizing the importance of public engagement, particularly as the Latino community continues to be criminalized while receiving some of the lowest wages in the country, public outreach is urgent. The public history project and non–profit “Refusing to Forget” thus applied to the Texas Historical Commission (THC) in 2015 to honor the contributions of Idar. The THC approved the marker and in 2017, it installed the marker in St. Peter’s Plaza in downtown Laredo .

Standing tall right across from a school, young people and residents all have direct access to this publicly displayed memory of Idar’s presence in this region; installed only a few miles from the third busiest international bridge in the country, the “Jovita Idar” marker is equally accessible to Mexican nationals and other visitors. It stands as an example of how a recovered history of a long–time labor and civil rights leader can be seen and reflected upon by all, not just by historians. Presenting a brief narrative of Idar’s life, the text on the marker concludes “until her death in 1946, Idar was dedicated to improving the lives of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, women and children through her writings and activism.”

A champion of Mexican American civil rights, Idar embodied the ideas of reform and uplift circulating in the progressive–era United States. Yet her lived experience as a fronteriza or border native made her progressive politics take on Mexican characteristics reflecting deeper gender reconfigurations occurring as Mexicans called for Revolution. Hailing from an affluent background and from family origins in the newspaper business, Idar represented the long history of cross–class alliances that unfolded in Mexico’s northern borderlands years prior. Cognizant of the power of labor organizing, particularly as her brother Clemente organized for the AFL and having witnessed the exclusion of women in many labor collectives, she became a formidable activist.

Besides implementing culturally relevant education, and her role in the formation of early women’s leagues and suffrage, she contributed to the expanding literary and intellectual world of Mexican American thought via Spanish and English language newspapers. This gave her a public forum by which to address the plight of the laboring masses along the southern border. She became involved with issues directly tied to the predominantly Mexican origin working–class, including challenging anti–Mexican violence.

In 1910 she protested the lynching of 14–year–old Antonio Gomez in Milam County, Texas. Three years after the horrific lynching, she wrote a scathing critique of President Woodrow Wilson’s decision to send nearly 12,000 US soldiers to the southern border, which built upon President William H. Taft’s earlier tactics of dispatching troops. Progressive–era nation building based on exclusionary policies intensified the racialization of Mexican Americans. This helped to fuel the labeling by Anglos of all Mexican origin people North of the border as potential ‘Mexican bandits.’ Such developments helped to harden racial boundaries and involved the sexual policing of women, particularly those engaged in the so–called public sphere, like Idar. Mexican American women, who transgressed perceived normative behavior, like other women of the period, were cast as lacking morality and decorum.

The discourse on the dangers of banditry and the need to eliminate any obstacle to state progress— through any means necessary— intensified as the nation entered the Great War. Heightened fears of foreigners importing radical ideas, particularly about labor rights, threatened the whole enterprise of capitalist development (on both sides of the Río Grande), and led to the Texas governor’s organizing of Loyalty Rangers to keep a watch on anti–war activity. By the summer of 1915 as Idar and her family continued to write in defense of the Mexican American community, the indiscriminate killing of Mexican origin people—including large swaths of the laboring classes as well as local Tejano officials— was unleashed at the hands of Rangers, vigilantes, or local law enforcement. As an investigative hearing in 1919 revealed, an abundance of evidence showed Ranger “gross violation of both civil and criminal laws,” yet no single officer was indicted (https://www.tsl.texas.gov/treasures/law/index.html).

Idar’s critique of Wilson’s militarization of the border did not result in change of policy, nor did her refusal to allow Rangers into a newspaper office with orders to shut it down end Ranger abuse of power. Yet, these events showcased her will and determination as well as that of an entire community to claim civic rights as full–fledged members of the very nation to which they claimed belonging. Idar’s intellectual critique against violence in defense of Mexican American workers, their children, and women’s “right to work,” combined with the legislative hearings about state abuse of power and its direct role in the attempted elimination of ‘the Mexican element,’ marked the beginning of a long struggle of belonging, civil rights, and uneven road toward gender equity.

Given the recent legislative efforts to censor any serious discussion about historical and present racism in places such as Texas public classrooms, resources such as the Jovita Idar marker are crucial to help larger publics access important histories. This, in turn, will help to expand discussion and remembrance of an often overlooked national hero.