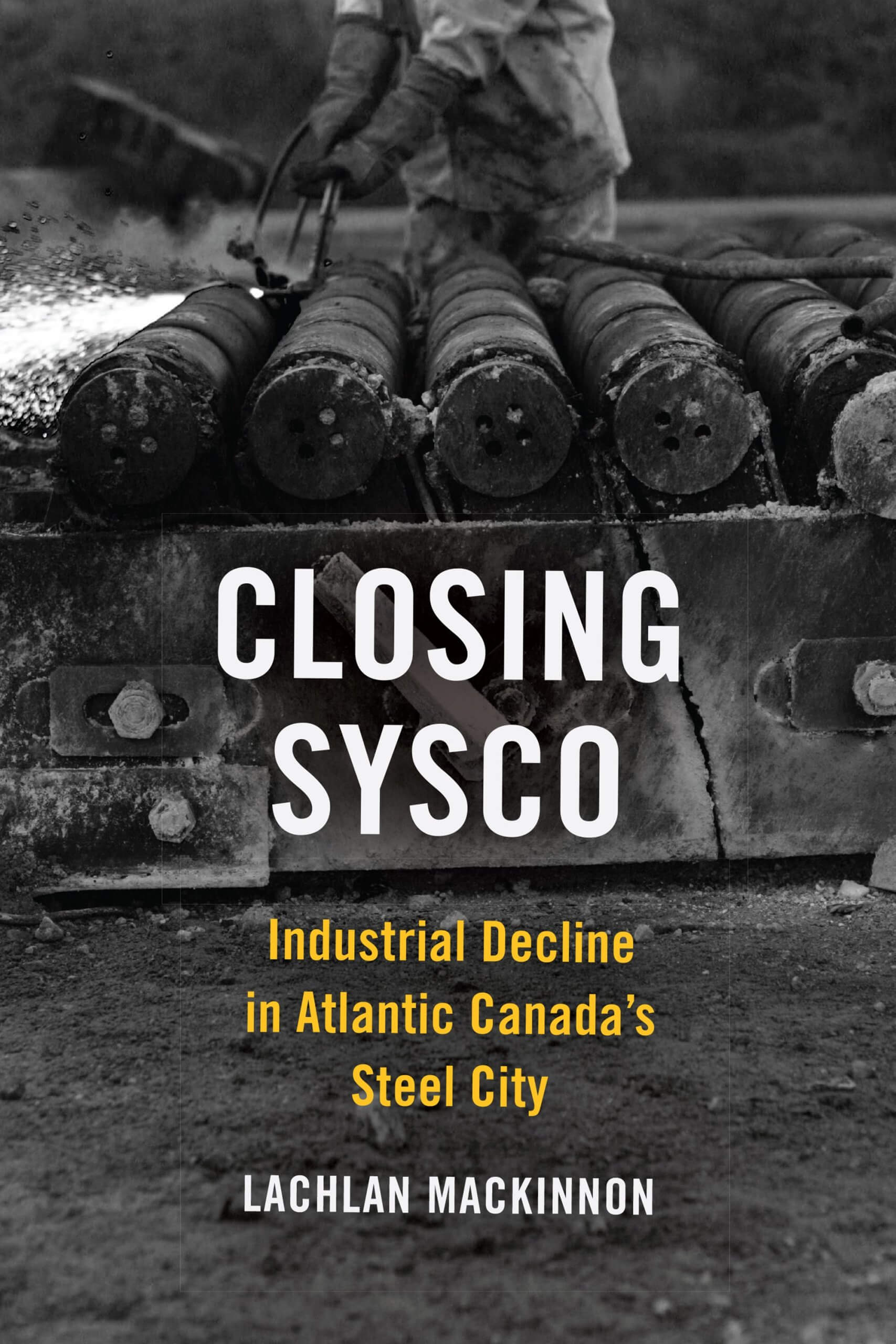

June 11 is Davis Day, a holiday originating in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, that honors the martyrs of the labor movement. It marks the day in 1925 when striking coal miner William Davis was shot and killed by police working to break a militant strike by UMW District 26 against the British Empire Steel Company. To commemorate Davis Day, we continue our series of interviews with authors of new books in labor and working-class history by talking to Lachlan MacKinnon about a later chapter in the labor history of Cape Breton. Closing Sysco: Industrial Decline in Atlantic Canada’s Steel City was published by the University of Toronto Press in February. MacKinnon, the Canada Research Chair in Post-Industrial Communities and an assistant professor of history at Cape Breton University, answered questions from Jacob Remes.

For people who aren’t familiar with Sydney and Cape Breton Island, can you give a brief introduction to the rise and fall of its steel industry?

The steel industry in Cape Breton was predicated upon the island’s bustling coal economy. Coal was mined on the island as early as the 18th century, but rapid industrialization during the 1800s greatly expanded the value of its coal resources. In 1893, Boston financier Henry Whitney established the Dominion Coal Company – followed in 1899 by the establishment of the Dominion Iron and Steel Company in Sydney. Whitney’s companies were vertically integrated; the coal from the Dominion collieries was used to fire the blast furnaces and coke ovens at the Sydney Steel Works. With this, the Sydney Works emerged as one of the four large integrated steel producers in Canada.

The Cape Breton labour wars of the 1920s saw protracted conflict between the island’s coal miners and steelworkers and the absentee capitalists who held ownership over those industries. Following the 1925 coal strike, famous for the murder of striking miner William Davis, the island’s industries were re-consolidated into a larger national firm – the Dominion Coal and Steel Company (Dosco). This was a significant turning point in the island’s industrial and labour history.

By the 1950s, Dosco was in crisis. It had fallen behind its central Canadian competitors for a variety of reasons, failing to achieve comparable rates of profit. In 1957, Dosco and its subsidiaries were purchased by A.V. Roe Canada, itself a subsidiary of the British Hawker Siddeley Limited. Between 1957 and 1967, a s

low liquidation occurred as maintenance was overlooked and equipment was slowly stripped from the Sydney Works. On “Black Friday,” October 1967, the company announced its planned exit from steelmaking in Sydney – a plan that would leave thousands of local steelworkers without employment. Local protests erupted and politicians scrambled to respond. Ultimately, the Government of Nova Scotia announced the nationalization of the Sydney Works and the formation of the Sydney Steel Corporation – Sysco – which would operate as a provincial Crown corporation.

The company remained profitable for the first years under public ownership, with steelworkers, their union – the United Steelworkers of America – and citizens alike applauding the notion. The necessary modernizations of the mill – long left unfulfilled in the Dosco years – remained a drain on provincial coffers. Combined with a series of poor investments throughout the 1970s, this meant that Sysco had amassed a significant operating debt by the 1980s – with very little in terms of modernization to show for it. During the 1990s, consecutive provincial governments failed to find a private buyer for the mill while community attention turned to the environmental and health effects of the “tar ponds.” In 1999, after the Tories were elected on an election platform that included the closure of Sysco, its closure was announced and the final rail was rolled in May 2000 – a century after production began.

The Cape Breton labour wars of the 1920s have received a great deal of scholarly attention. It was in the shadow of these events that the labour movement on the island became an integral part of mainstream culture. While the battles of the 1920s pitted radical labour against absentee capital and local overseers, the labour movement that took its shape in the aftermath of the Second World War was more bureaucratized. The Sydney steelworkers organized with the United Steelworkers of America in 1942, and one of the first major challenges they faced was the 1946 national steel strike. Nearly immediately, the steelworkers’ union recognized the difficulties facing the industry and the challenges that these posed to rural resource economies like Cape Breton Island. As early as the 1950s, the steelworkers’ union was directly involved in calling for state action to offset the threat of industrial closure – well before the industrial crisis of the 1970s and 1980s was brought into full view.

Much of your book is based on oral histories. Can you tell me more about that process?

I sat with approximately 30 people for extensive oral history interviews during the research for the book. Each of them, of course, provided something valuable – whether personal experiences, recollections, or ruminations of the politics of Sysco at the end. There were a few that I’d like to specifically mention.

Gerry McCarron – my wife’s uncle – was a fourth generation Sysco worker. He spoke with me several times about his own experiences at the plant, helped to arrange interviews with other former workers, and even sat in on several group interviews. Working with Gerry, I think, was a true reflection on what oral historians sometimes call “shared authority.” He and I still call back and forth when something related to the plant and its history pops up. It was a great experience.

Juanita McKenzie, one of the women involved in tar ponds activism, was another memorable interview. Juanita has such a strong sense of justice for the environmental and health issues relates to the toxification of the site – she lost one of her daughters at a young age to cancer after the events in the book. Her story is both touching and tragic; in our interview she reflected on the meaning of her former home on Frederick Street, alongside the plant, and the good and bad memories that sense of home engendered. It’s an interview and a story I’ll always remember.

Another memorable interview was with former Premier John Hamm, under whose government the plant was finally closed down. I remember – as a child – feeling so angry towards Hamm for having closed the plant. I think some of that anger went into my reasons for writing the book. But when we sat for an interview, I wasn’t speaking to the neoliberal ideologue that I perhaps expected, at some point. Rather, he saw himself as something of a neo-Stanfieldian – with no moral qualms about state interventionism in local economies. He felt, as he expressed, that state subsidy could be more profitably and equitably distributed if the costs of Sysco were off the books. That this would allow for better outcomes elsewhere, in the long run. He was just a person – influenced, of course, by the prevailing market-centric tradewinds of the 1990s, but not the villain of the story. As I say in the book, I think our conversation changed the book for the better – changing it from a “Who Killed Sydney Steel”-style settling of grievances into something that I think cuts through to some of the moral structural issues surrounding deindustrialization.

The closed steel industry didn’t just leave a post-industrial community; it left a post-industrial landscape, perhaps most notably in the Tar Ponds. How do you combine labor history and environmental history in your book?

This is one of the major contributions of the book. Too often, especially in popular media, we are presented with the notion that there is some irrevocable conflict between “jobs” and “the environment.” In Sydney, we see that this was not the case. Workers in the plant’s coke ovens were conducting grassroots environmental and occupational health research well before popular attention turned towards these issues. As men and women who lived and worked in the streets around the plant, steelworkers and their families also had a direct interest in fighting for a healthy workplace and a healthy community.

Of course, this is also where solidarity can begin to fracture; the book explores the class divisions that emerged around the tar ponds issue from a variety of perspectives – from the “front porch politics” practiced by local working-class women to the involvement of national environmental organizations like the Sierra Club of Canada. Most importantly, I think, are the human voices that bring these challenges into stark relief; in these chapters, the true impact of industry and deindustrialization are laid bare.

What lessons can the aftermath of Cape Breton’s steel industry teach us about industrial decline and change in other parts of North America?

I think there are a few lessons that Sysco provides that can be applied elsewhere.

The first is that deindustrialization is not inevitable and public intervention should not be seen as doomed to fail. None of this was preordained, but the end of Sysco was the result of specific decisions of various provincial governments from 1967 until 2000. Indeed, public ownership at Sysco – in the sense of purposeful, long-term operation for profit by the state – was never really the intention. From the moment of nationalization, the intent was to keep the mill operating only as long as would be possible until a private buyer could be found. Various changes in provincial governments changed the terms of this calculation at different times, from modernization spending to prospective plans such as CANSTEEL, but that core value remained the same. Had governments been fully committed to Sysco at the moment of its inception – with timely investment on modernization and upgrading, there is no reason why it could not have remained profitable.

The story of Sysco and the tar ponds also lays bare one of the fundamental contradictions of capitalism. We had a privately owned steel firm that produced and sold steel for 67 years, using the labour of the men and women who lived around it to massive profit, before shuttering its doors and leaving the provincial and federal governments to deal with the aftermath. The “externalities” of this process include hundreds of millions of dollars in expense to Canadian taxpayers for the clean up and remediation of the site, not to mention the variety of chronic illnesses and cancers among steelworkers, their families, and other community members. The labyrinthine way that this story played out is truly shocking.

Now that you’re done with your book, what books are you looking forward to catching up on?

I’m currently working through Tim Strangleman’s Voices of Guinness: An Oral History of the Park Royal Brewery (OUP, 2019). Ben Harker’s The Chronology of Revolution: Communism, Culture, and Civil Society in Twentieth Century Britain (University of Toronto Press, 2020) is also on the list, as is Shirley Tillotson’s Give and Take: The Citizen Taxpayer and the Rise of Canadian Democracy (UBC, 2017). I also have Peter Thomson’s Nights Below Foord Street: Literature and Popular Culture in Post-industrial Nova Scotia (McGill-Queen’s 2020) on order. I could go on and on.